SFU Faculty perspectives on open access and the University of California's Elsevier cancellation

Published April 8, 2019 by Kate Shuttleworth on the Radical Access Blog

The University of California recently took a bold step in support of open access publishing by terminating subscriptions with Elsevier, the world’s largest scientific publisher. We asked SFU Faculty for their thoughts on the cancellation and what this means for open access.

What happened?

The University of California is committed to making the results of research freely available to anyone, anywhere in the world through open access, as indicated by UC's faculty-driven principles on scholarly communication and its Open Access Policy which was adopted in 2013. Elsevier charges academic libraries for access to subscription-based research articles, while at the same time charging Article Processing Charges for open access articles published by UC researchers.

UC was attempting to negotiate a deal with Elsevier which would see the costs of subscription journals offset against the cost of open access publishing in order to ensure cost neutrality in the shift towards open access. When a deal could not be reached, UC canceled its Elsevier subscriptions with support from faculty and the Academic Senate, and provided a set of alternative solutions for accessing content when Elsevier begins limiting access to new content.

Read what SFU faculty had to say about the cancellation on the Radical Access blog.

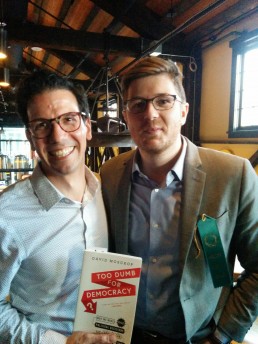

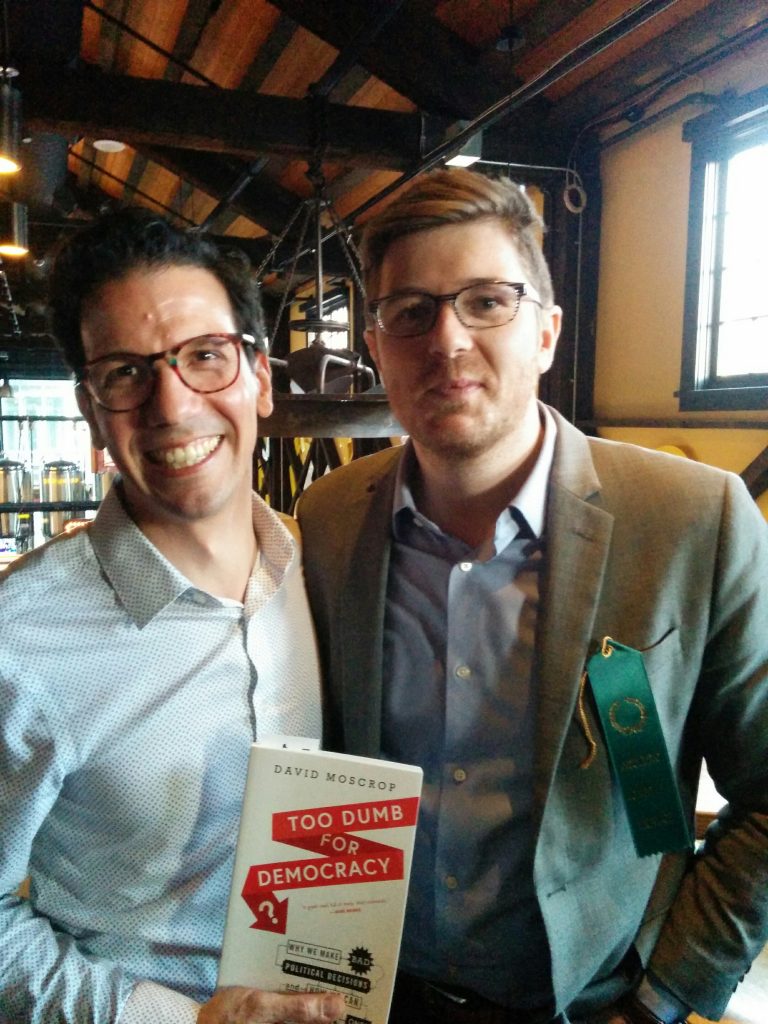

David Moscrop launches 'Too Dumb for Democracy?'

"The good news is, we're not too dumb for democracy," David Moscrop told a packed room of media, activists, book lovers, academics, and more. "The bad news is, we're encouraged to be."

On March 21, Moscrop celebrated the launch of his new book, Too Dumb for Democracy? (Goose Lane Editions, 2019). In this compact volume, he distills lessons from political science, psychology, and his own experiences as a political theorist to explore why we make such irrational political decisions—and how we can learn to make better ones. He also explains why, "in an era overshadowed by income inequality, environmental catastrophes, terrorism at home and abroad, and the decline of democracy....the political decision-making process has never been more important." Improving the way we make decisions, he argues, may be our only hope for survival.

Moscrop has written about these issues before. His work has been featured in outlets such as Maclean's, the Washington Post, and the National Post, and he is a frequent guest on CBC radio, among other programs.

But Moscrop does more than provide political commentary. He also conducts research on democratic deliberation, political decision making, and digital media—including a study on political pundits' use of Twitter, which he is working on with the ScholCommLab.

We're excited to congratulate Moscrop on this accomplishment, and can't wait to see what he has planned next.

To find out more about Too Dumb for Democracy?, visit Goose Lane Editions' website.

Making Knowledge Public: Student reflections on the 2018 President’s Dream Colloquium

First published on February 28, 2019 on the Radical Access Blog.

Changing the academic system to be more accessible

“You shouldn’t have to pay a large sum of tuition to have access to basic information,” Melissa Roach says when I ask her what she’d like to change about our academic system. “It just creates layers of mediation between scholars, media and the public, and that disconnect can cause a lot of misunderstanding.”

Roach is a fourth year English student at SFU, a Communications Coordinator for SFU’s Vancity Office of Community Engagement, and a former news journalist. She’s also one of 11 students who participated in the President’s Dream Colloquium on Making Knowledge Publicwith me last fall.

A colloquium exploring research and society

Part public speaker series, part seminar course, the colloquium brought together students from across the university in a wide-ranging exploration of how research makes its way into society. Over the course of the semester, we attended public lectures and seminars with leading experts; added public commentary to our course readings using a tool called Hypothes.is; and produced an eclectic mix of final projects—all of which are publicly available in the Course Journal for Making Knowledge Public. By enrolling in the colloquium, we didn’t just learn about making knowledge public; we actively participated in the process.

Students share their thoughts on making information public

But the format wasn’t the only thing that made the course unique. With students spanning academic disciplines, education levels, and interests, our cohort was one of the most diverse I’ve ever been a part of.

To find out more about how others experienced the colloquium, I interviewed three of my classmates—Melissa Roach, Carina Albrecht, and Kari Gustafson—and asked them for their thoughts on making knowledge public.

How did this course differ from other learning experiences you’ve had?

MR: “It was great to meet so many people from different disciplines and also pursuing so many different levels of education. The climate within the classroom and the kinds of conversations we were having was different from almost every other class I’ve taken. The classroom felt like a really good space to be in. Everybody brought such different perspectives to it.”

“The climate within the classroom and the kinds of conversations we were having was different from almost every other class I’ve taken.”—Melissa Roach

CA: “If I had to define it in a word it would be engaging. It was fun to come to the class! The mix of public lectures and private classes was really interesting. You get perspectives from outside of the classroom—not only from your professor. To learn from other people and experts, that really was a privilege.”

KG: “I really enjoyed doing the online reading annotations with hypothes.is. It was a really good learning tool. I could have taken notes for myself on a PDF—annotated things to bring to class to talk about. But somehow having the possibility of actually having the discussion in the same moment that I was reading about it felt really good.

What was it like having to do all of your work in public?

MR: “It was a little intimidating! When I went into the course, I was expecting to do something around science communication for my final project, around helping others share their research work. Amplifying the voices of others is what I do in my work as a communicator, so I decided to put my own ideas out there instead and I’m glad I did. I think it was a good challenge.”

CA: The feedback was good, especially for our Medium article on the public’s perceptions of university knowledge production. We put our blog post out there, and we weren’t expecting much of it. It was just an assignment. But the response that we got from the public was exciting. It was clearly a topic that people were interested in. Getting a sense of what other people were thinking about this topic was really cool.”

“It was extremely useful being forced out into public commentaries. I don’t like to tell people when I think they’re wrong, so I usually don’t. It was really good to get over that hurdle.”—Kari Gustafson

KG: “I liked it. It was extremely useful being forced out into public commentaries. I don’t like to tell people when I think they’re wrong, or sound like a know-it-all, so I usually don’t. I’ll read something, but I won’t actually take the next step, which is to comment on it or formulate that thought in a way that makes sense. It was slightly anxiety-inducing, but also really good to get over that hurdle.”

Did the course change your thinking in any way?

MR: Before taking the course, I was of the attitude that my academic work wasn’t really valid unless some other person or publication decided that was worth sharing. To have Juan [Pablo Alperin, the course instructor] say, “Go ahead, post it on the internet. You can do that.” Mind blowing.

CA: I think that the most valuable thing that I learned from the course was about how academia works: the process of publishing, what is open access, what is not. I had no idea about all of that going into the course. We have this idea that academics just need to write articles and publish them, and that’s all making knowledge public is. But it’s way more complicated than that.”

"We have this idea that academics just need to write articles and publish them, and that’s all making knowledge public is. But it’s way more complicated than that.”—Carina Albrecht

KG: “I’d always been interested in open access journals. But now I’m going to insist on never publishing anything that’s not open access. I’m absolutely committed to publishing only open access!”

How do you feel about making knowledge public, now that the course is over?

MR: “That was the big question at the end [of the course], ‘How do you feel now?’ I think I have very mixed feelings. I think that being aware of the systemic obstacles to practicing public scholarship and being inclusive as a university—at least knowing what the challenges are—that’s where you can be optimistic, because you know what needs to be worked on.”

CA: We brought up a lot of problems during the course. I left with the impression that making knowledge public is really hard, and that we have a long way to go before we can actually get to a good place. I think it is an achievable goal, but I think that we’re moving toward it in slow motion.”

KG: “The course made me rethink the question of, 'What is my role as an educated person?' I had always thought about the elitist aspect of making knowledge public—that I shouldn’t sound like I know more than other people do—and not so much about the fact that sharing knowledge is actually a responsibility.”

What are you planning to do next?

MR: “I don’t really have plans to be a career academic. But one thing I took out of this class is that you don’t have to be at an institution to always be learning, or to make an impact in your community. That was one thing that was kind of inspiring to me, that I don’t have to pay for a graduate degree to keep working on issues that are important to me—especially if the scholarly world gets its act together and all the journals become open access!”

CA: “The course gave me an awareness of my own future. I want to be in academia. But now I’m going into it with different eyes, especially when it comes to the expectations for tenure and promotion in your career. Learning about those was really a bit of a bummer for me. But it’s better to know before than after.

KG: “My dream job would be to teach at a community college or rural branch campus, and work on small, action research-type projects. Education—or knowledge—shouldn't just be for "elite" students or those able to study full-time in urban areas. It should be local, situated, affordable—preferably free—and universally available regardless of ability, age, and income.”

Want to learn more about Making Knowledge Public? All of our course readings, lectures, and assignments are available online for anyone to enjoy. Interested in launching a course journal for your class similar to the Course Journal for Making Knowledge Public? Contact Digital Publishing at SFU Library: digital-publishing@sfu.ca

Kathleen Fitzpatrick on the Power of Generous Thinking

“What might be possible for us if we were to retain the social commitment that motivates our critical work, while stepping off the field of competition?” Kathleen Fitzpatrick asked a rapt audience at SFU’s Harbour Centre last Wednesday, “We would have to open ourselves to the possibility that our ideas might be wrong.”

Fitzpatrick is Director of Digital Humanities at Michigan State University, the former Director of Scholarly Communication at the Modern Language Association, and—most recently—the invited speaker at this year’s Munro Lecture at SFU.

Named after Jock Munro—an economist and former SFU Vice-President, Academic—the lecture series has hosted a number of acclaimed scholars over the years, including Linda Tuhiwai Smith on decolonizing the research process and Arthur Hanson on China’s green economy. This year’s edition continued the conversation started during last fall’s President’s Dream Colloquium on Making Knowledge Public.

In her talk, Fitzpatrick discussed the individualistic nature of academic life and how it impedes the relationships that exist between universities and the communities that surround them. Drawing from her newly released book, Generous Thinking, she explored the many challenges that stand in the way of a more engaged academic system and offered a radical approach to how overcoming them—starting with a complete shift in how we think about public scholarship.

Her passionate appeal resonated with many in the audience, with nods, sighs, and the occasional “Yeah!” permeating the presentation. “Generous thinking,” it seems, had been on many listeners’ minds.

As John Maxwell, Director of SFU’s Publishing Department, aptly put it, “Kathleen Fitzpatrick has elegantly articulated what many academics have been thinking—that the black and white framing of university and society is not serving anyone well, and that our culture of internal competitiveness undermines any effort to be engaged and relevant.”

So what can today’s academics do to become more engaged, relevant, and connected?

“All… possibilities begin with cultivating the ability to think generously,” Fitzpatrick offered at the end of her lecture, “To listen to one another.”

Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s Munro Lecture on Generous Thinking was presented in partnership with the SFU President’s Office, SFU Public Square, and SFU’s School of Publishing. For those who missed it, a video is available from the SFU Library.

Meet our Spring Visiting Scholars | Interview with Iara Vidal, Isabelle Dorsch, and Lisa Matthias

The ScholCommLab is excited to welcome three new faces to the lab this spring. Iara Vidal, Isabelle Dorsch, and Lisa Matthias will join us as Visiting Scholars in each of our two locations—Matthias and Vidal in Vancouver, Dorsch in Ottawa—to collaborate on a research project of their choosing.

Vidal has a background in library science and is currently finishing her PhD in Information Science in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Dorsch is a research associate and PhD candidate from Düsseldorf, Germany, who is passionate about social media and infometrics. Matthias is a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of North American Studies at Freie Universität Berlin with a deep interest in open science, scholarly communication, and mental health.

In this interview, they offer a glimpse of their upcoming research projects and share their thoughts on collaboration, public scholarship, sushi, and more.

Why did you apply to the ScholCommLab's Visiting Scholar Program?

Iara Vidal: I’ve been following the work of Dr. Stephanie Haustein and Dr. Juan Pablo Alperin for some time, and I believe some of the most interesting research on scholarly communication right now is coming from the ScholCommLab team. When I saw the visiting scholar's call I knew I couldn’t miss that chance!

Some of the most interesting research on scholarly communication right now is coming from the ScholCommLab team. When I saw the visiting scholar's call I knew I couldn’t miss that chance!

Iara Vidal

Isabelle Dorsch: I wanted to apply for the program because my research interest on “metric-wiseness” fits perfectly with the metrics-literacy project Dr. Stefanie Haustein and her team in Ottawa is conducting. I thought it would be really cool to be part of it and to work together on this topic!

Lisa Matthias: High spirits and sheer optimism!

Tell me about your research. What topic or area you most interested in right now?

IV: My PhD research explores different aspects of altmetrics for Brazilian research articles, particularly whether there’s any relation between coverage in Scopus and/or Web of Science and altmetric attention. In other words, I’m asking: Can altmetrics shed light into research that is “invisible” because it is not indexed by mainstream databases? Another question is if Brazilian open access articles get any more attention than the rest of our output.

ID: Scholarly communication and the use of scientometric indicators is one of my research interests right now. Likewise, I concentrate on social media research with special focus on hashtag usage and visual content on Instagram.

LM: My background is in political science with a focus on US media and political polarization, but for the last two years, I have also been actively involved in scholarly communication projects. At the ScholCommLab, I will take a closer look at how the media uses scientific research on opioid addiction prevention, harm reduction, and treatment in their coverage of the opioid epidemic.

How do your personal research interests intersect with the ScholCommLab's?

IV: The ScholCommLab does great work in both altmetrics and open access, often from a Latin American perspective. I’ll be working with Dr. Alperin and other Brazilian researchers in a project that also deals with Brazilian research, but instead of altmetrics we’ll study internationalization.

ID: I was lucky enough to be part of a ScholComLab meeting in November 2018 in Vancouver. There, I was introduced to all their current projects, and I often found myself thinking, “Oh, this is interesting too.”

I want research to be open, transparent, and unrestrained, instead of being governed by fear, elitism, and economic interests.

Lisa Matthias

LM: My research interests are the ScholCommLab's! I do not believe that our current ways of conducting, disseminating, and communicating research are the most effective in advancing science or society…. I want research to be open, transparent, and unrestrained, instead of being governed by fear, elitism, and economic interests.

Why does international collaboration matter to you?

IV: I believe research is all about learning from each other and building on each other’s work. That’s why international collaboration is important to me, you can have different perspectives on a subject and the resulting work will be richer for that.

ID: In my opinion, it is important to approach other people and institutions and exchange ideas, instead of simply doing our own thing. To be able to do this, international collaboration is indispensable. It helps us improve ourselves—or, rather, everyone who is engaged—on so many different levels.

International collaboration is indispensable. It helps us improve ourselves—or, rather, everyone who is engaged—on so many different levels.

Isabelle Dorsch

LM: Because it gives us the opportunity to learn from and connect with each other. International collaboration brings together not only different skill sets, but also cultures, perspectives, and experiences, and this enables us to challenge accepted ideas and bring about change. If you look at the bigger picture, I believe that the global challenges we are currently facing can only be addressed effectively if we work together globally.

What are you most excited or curious to try during your stay in Vancouver/Ottawa?

IV: This will be my first time in Canada and my first time living abroad, so I’m really excited! I’ve heard only good things about the city and am very curious to explore it.

ID: Since it is my first time participating in a visiting scholar project, I’m generally excited about the possibilities it will provide. I’m definitely curious to discover new foods and other things that might not be available in Germany.

LM: How to eat as much sushi as humanly possible?! Vancouver is one of my favourite places in the world and I can't wait to be back! Let's limit the list to five (excluding the sushi): Nerd Nite; beating my Grouse Mountain hike record; anything to do with mountains, actually; seeing David August live (apparently, Berlin techno is following me to Vancouver); and spending time with you all!

Iara Vidal, Isabelle Dorsch, and Lisa Matthias will be working with the ScholCommLab throughout spring and summer 2019. Find out more about our Visiting Scholar Program on our website.

Making Research Knowledge Public Award | Interview with recipients Hannah McGregor and Juan Pablo Alperin

“Sometimes people need to be told that your work is for them, or invited in some way,” says Hannah McGregor, an assistant professor in Simon Fraser University’s Publishing Department and the host and producer of the podcast Secret Feminist Agenda. “There are lots of ways to invite people into your work, but I think one of the best is to think about the kind of language and media that you use.”

The podcast, which she describes as “a weekly discussion of the insidious, nefarious, insurgent, and mundane ways we enact our feminism in our daily lives,” is just one of the many ways McGregor invites the public to engage with her work. She’s also active on social media, a co-editor of a new book exploring the state of Canadian Literature, and the organizer of Publishing Unbound, a workshop that brought together authors, activists, scholars, and publishing professionals to discuss inclusivity and accountability in Canadian Literature.

As of this December, she is also a co-recipient—with ScholCommLab director Juan Pablo Alperin—of the inaugural Research Excellence Award for Making Research Knowledge Public. Adjudicated by a university-wide panel, the award was jointly presented to the duo in recognition of their “demonstrated excellence in making research outcomes and insights public and in engaging new communities with scholarly or artistic work.”

Like McGregor, Alperin is an assistant professor in the Publishing Department and a strong believer in the importance of public scholarship. But while McGregor takes a public-focused approach to making research knowledge public, Alperin’s work is centred within the academic system itself—dedicated to investigating the ins and outs of open access publishing, the barriers that prevent academics from engaging in public scholarship, and more.

In celebration of the award, we asked Alperin and McGregor to share their views on making research knowledge public and the challenges that sometimes stand in the way.

What does "making research knowledge public" look like to you?

Juan Pablo Alperin: I see open access as a very basic, initial step toward making research knowledge public. We never know who in society might care about our work, regardless of how niche an audience we might have in mind. My own research and other evidence points to the fact that there are members of the public who want to know. Even if faculty don’t want to change anything else about what they do, they can make sure that their research is at least accessible to anyone who wants to see it. For me, making research knowledge public is about enabling and supporting an ecosystem in which that becomes the norm.

Hannah McGregor: I think open access should be the default and baseline, particularly for journals. But access goes beyond just paywalls; it also has to do with language and discoverability. Journals—open access or not—still circulate within particular systems of discoverability that are available mostly to people who know how universities work.

The side of things that I have been working on is what my colleague Jon Bath calls public-first scholarship. I’ve been thinking about what it means to do your work in the public from the get-go, rather than doing it within the university and then making it public later. I’m making podcasts, because podcasts are not a university medium. They are a medium that has their own logic, a logic that is inherently open and inherently public-facing. I want the audience for my work to not be precluded by people who have access to scholarship.

What are the top challenges when it comes to public scholarship?

JPA: What I see as the biggest challenge is getting academics to think and care about non-academic audiences—to start believing that making research available matters. Everyone cares in a very abstract way, but not everyone thinks about non-academic audiences as important constituents who they have a duty to share their work with. We need to shift that perspective so that faculty see public scholarship as a primary objective of their work, and not way down the list of things they have to do. We need to make it a priority.

"We need to shift that perspective so that faculty see public scholarship as a primary objective of their work, and not way down the list of things they have to do. We need to make it a priority."

Juan Pablo Alperin

HM: For me, it’s the finitude of our time and energies. I’ve been working on my podcast for a year and a half. I love making it, but I also can do almost nothing else while I’m working on it. Many, many scholars doing this kind of work have been facing this challenge for ages: you end up having to do twice the work. You have to do all of the traditionally recognized scholarship in order to secure a job and then secure promotion and tenure. But at the same time, you want to do this other work—the work that, in my view, really matters.

The podcast is great and brings me a lot of public interest in my work. But can I get tenure for a podcast? Maybe not.

If you could change one thing...

HM: I’d like to see some pretty significant transformations in how, at the departmental level, research is valued. I think non-traditional scholarly options need to be taken seriously as the primary output of scholars. Based in part on conversations that I’ve had with other academics and in part on research that came out of this lab on public scholarship and the degree to which it’s represented in tenure and promotion documents, we know that the vast majority of university departments do not care about public scholarship. They care about published journal articles in peer-reviewed journals. People have finite energy, and if one thing is going to get you a job and the other is going to get you a thumbs up, but ultimately no financial security, what thing are you going to choose?

"Non-traditional scholarly options need to be taken seriously as the primary output of scholars... People have finite energy, and if one thing is going to get you a job and the other is going to get you a thumbs up, but ultimately no financial security, what thing are you going to choose?"

Hannah McGregor

What do you think researchers could do better?

JPA: There’s a lot more that could be done around sharing, disseminating, and talking about our work in a wide range of venues. We need to look for broader audiences for our research—be that by posting on social media, doing outreach to media, or creating infographics and other simplified forms of communicating our results.

We need to widen our conception of who our audience is. An audience could be anyone, so just put your research out there in slightly different forms and different ways—as many as come to mind and as you have time and resources for.

For more information about the Research Excellence Awards, visit FCAT's website.

Why Research Communication Matters - Q&A with Michelle La

How can scholars communicate their work in more accessible, engaging ways? Where should they publish and promote their findings? What does “research communication” actually mean?

On Tuesday, January 15, ScholCommLab researcher Michelle La will explore these questions and more in a short talk at SFU’s Graduate and Postdoctoral Student Photo Reception. Featuring top photography by graduate students and postdoctoral fellows from across the university, this interdisciplinary event is the culmination of three “epic” summer photo contests: Show Us Your Research, Decolonizing the Academy, and Show Us Your Home. La’s presentation will focus on the first of the three themes, highlighting the importance of using diverse research communication strategies—from photography to soundscapes and everything in between.

In anticipation of the event, we sat down with La and talked research tips, communication challenges, imposter syndrome, and more.

What does research communication mean to you?

Research communication means trying to reach different audiences. No matter what form it takes, for me, the most important thing in research communication is to de-jargonize your work and make it accessible for a wider audience. Because research often is just shared right to our own peers, within or our own circles. Research communication is about trying to go beyond your immediate audience.

Do you think the academic community is changing its approach to research communication?

Things like SFU’s 3MT competition are evidence of an ongoing push to make research more accessible. You’re given three minutes and you have to talk about your thesis research within that time frame to a general audience who doesn’t know anything about it, and you have to convey why it’s important.

I think that these competitions are part of a larger movement of academics who are being self critical—asking questions like, Who are we writing to? Who is this research for? So too are initiatives like open access or open pedagogy or open scholarship. We’re trying to train our students to speak to a greater audience.

What do you see as one of the biggest barriers preventing researchers from making their research more accessible?

I think we have to have confidence in ourselves—confidence that our research is important. We’re told all the time that we’re never enough as grad students, that we never know enough. We have to let go of this idea of the imposter syndrome.

“We have to have confidence in ourselves—confidence that our research is important….We have to let go of this idea of the imposter syndrome.”

I think that, a lot of the time, people are shy—especially if they’re in a discipline that uses very esoteric terminology, like molecular biology. But if you can learn how to frame your research in a way that helps others see the bigger picture of why your research is important, I think you can get over that barrier.

It’s also a question of putting yourself out there. A lot of academics don’t want to put their work out into the public unless they know it’s really good. And I think that we have to get over that mindset and just take risks. I think that’s the biggest thing: to not be afraid to pitch your ideas.

How have your own experiences presenting your graduate research informed your approach to communication?

I haven’t engaged in that many diverse forms of research communication, but I would say that since I did the 3MT, I feel confident that I can do this, and I can apply that skill to different types of mediums.

I want people to know that this really is a skill. It’s not an innate talent that some people have and others don’t. Research communication is just practice, opening yourself up to different venues, and advocating for yourself. We need to learn to self-promote! This is the reality that we live in.

What are you planning to focus on in your talk ?

For me, I want to talk about how beneficial practicing research communication is for the researcher. It helps you hone in on what’s really important, what the bigger picture is, what your research focus is, and I think it makes you more confident and eloquent.

I also think it’s something we should do for ourselves, because we work so hard on our graduate research. We spend so many hours, so many months. We owe it to ourselves to share what we’re doing. If you communicate research in an effective manner, you may learn that the audience who appreciates it is a lot broader than you think.

Any final thoughts?

Open access! That’s one last thing I’m going to talk about. We need to think about sharing the results of our research not just through the formal journal, but also in other areas. That’s another part of research communication, the platforms we choose to share our research on.

If we want knowledge to be accessible, then we have to walk the walk. We can’t just talk the talk.

Reserve your spot for this FREE event at eventbrite.ca.

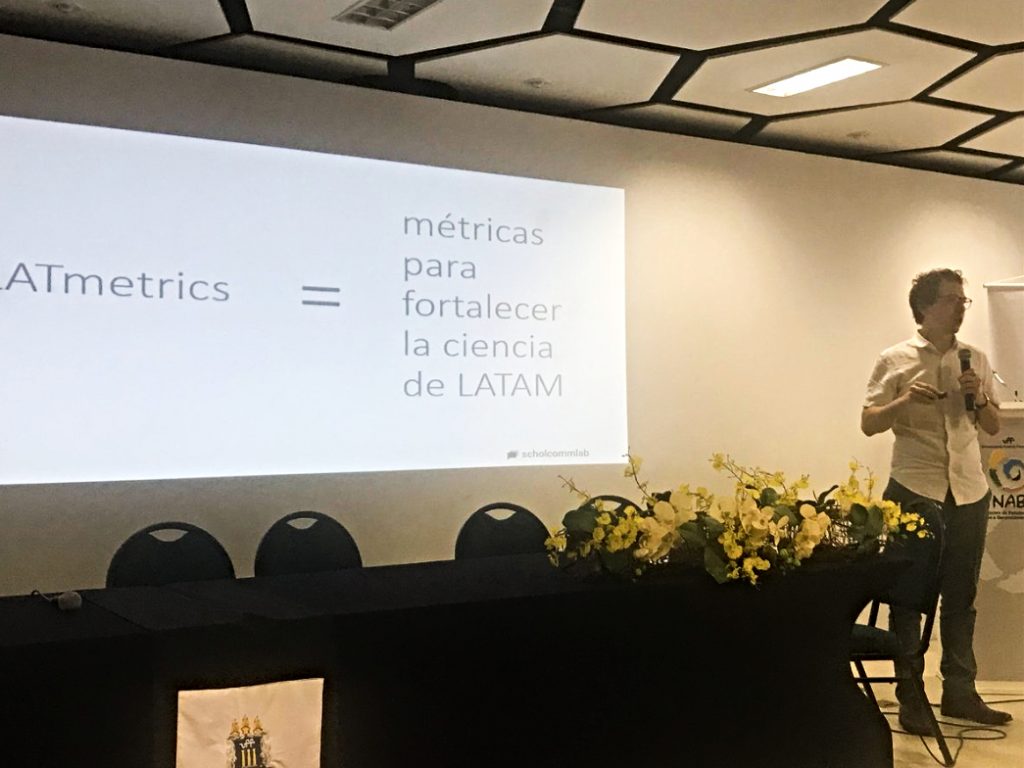

Reflections on the Inaugural LATmetrics Conference

This November, the city of Niterói in Rio de Janeiro received the first edition of LATmetrics, an international conference dedicated to the advancement of altmetrics and open science research in Latin America. Bringing together researchers, science communicators, librarians, and other stakeholders, the event featured a diverse array of speakers on everything from social media metrics and open data to the impact of science in society.

ScholCommLab co-director Juan Pablo Alperin was on the scientific committee for the conference, and co-presented the closing keynote. Here’s what he had to say about this landmark event and the future of Latin American metrics research.

LATmetrics’ website says we are experiencing “a moment of effervescence for both scientific communication and the geography of science”. What makes 2018 such an important time for a conference like this to take place?

There’s two parts to it. One is the growing number of researchers from Latin America who are interested in open science and metrics, and in particular, altmetrics. There’s an opportunity to create a new community around these folks—one that is not immediately tied to open science and altmetrics in the so-called “global” context, which is essentially based in North America and Europe.

But it’s also an opportunity to see what is unique about the region when it comes to these issues. LATmetrics was a first attempt to explore whether there are challenges or opportunities related to altmetrics or open science that are specific to Latin America and may not be coming up in other discussions, and whether there are ways of analyzing and thinking about those issues from within the region itself.

You were on a closing ceremony panel about the “Impacts of Open Access in Latin America”. Can you share what you discussed?

There were two of us on the panel, Dr. Sarita Albagli and myself. Both of us, without having coordinated about it at all, gave slightly different perspectives on the same message: the need for Latin American independence when it comes to how we see open science and calculate scholarly metrics. I mostly addressed this from the metrics perspective, with the core message of my talk being that I don’t want Latin American metrics to become global metrics done by people from Latin America. I want them to be metrics that are purposefully trying to strengthen Latin American science. Dr. Albagli gave a similar talk around independence and the intellectual liberation of Latin America science, speaking from an open access and open science perspective.

“I don’t want Latin American metrics to become global metrics done by people from Latin America. I want them to be metrics that are purposefully trying to strengthen Latin American science.”

“I don’t want Latin American metrics to become global metrics done by people from Latin America. I want them to be metrics that are purposefully trying to strengthen Latin American science.”

I think it’s telling that we both chose to close off the conference speaking about regional independence rather than giving a more research-oriented talk. There are a number of relevant projects we’re working on here at the lab that I could have highlighted, but I didn’t want to talk about data or results. I wanted to drive home a message: I really don’t want Latin American metrics to become a community that just replicates Northern metrics.

What sets Latin American metrics apart from other metrics communities?

There are still contentious debates about what metrics should use to assess research. If we adopt the Northern research evaluation culture, I don’t think it’s going to lead to better science. There is an opportunity to develop metrics that make the region more conscious of what it does have. For example, Latin America already has a scholarly owned and operated publishing infrastructure in place, while the rest of North America is still looking for one. Yet Latin America is selling its journals. We should be developing and encouraging the use of metrics that highlight this. I hope we can create a community that appreciates what will make Latin American science thrive, instead of metrics that see us give up the our science sovereignty.What was a highlight of the conference for you?

Rio is such a beautiful place, so we were surrounded by this amazing environment. But there was also this warm, social connection between folks at LATmetrics that I think is lacking at many of the conferences I go to in North America. It was a similar feeling I had with the Latin American group at OpenCon. While I’m friendly and have fun at conferences everywhere, there was a sense of community at this event that really drew people together.

"For me, at all these conferences, it’s never about the talks. It’s about the social connections you make."

For me, at all these conferences, it’s never about the talks. It’s about the social connections you make. By building communities of people who share similar concerns, these events create friendships and bonds that drive collaboration and idea sharing.

Two other ScholCommLabbers were at the conference as well: former Visiting Scholar Germana Barata gave a talk on the social performance of medical journals, and future Visiting Scholar Iara Vidal de Souza presented work on the advantage of open access and Brazilian publications. Why are international relationships so important for the lab?

My upbringing in scholarly communications started within a Latin American context. But being based here in Canada, it’s so easy for me to tackle projects and problems that are “global” in scope—that is, largely focused on North America or Europe.

So when Germana joined the lab, it was an opportunity to put down one more anchor in Latin America. It’s important for me to maintain that connection, to keep in contact with people who are really on the ground, with the lived experience of being in Latin America that I lack.

Hosting Germana also paved the way for future collaborations with Brazil. Her stay allowed other Brazilian scholars to realize that working in a lab in Canada was an achievable thing. So when we put out our call for the visiting scholar program, we were excited to see we had seven or eight really strong proposals from Brazil. As soon as you forge these kinds of connections, you open up channels for collaborations.

What’s next for LATmetrics?

Next year, the organizers are hoping to repeat the conference again in Peru. I’m already looking forward to the next event. LATmetrics is at the intersection of all of the things that I do: open science, metrics, and Latin American issues. I’m curious to see where this community goes, and I think this conference was a great foundation.

To find out more about LATmetrics, visit latmetrics.com.

ScholCommLab Welcomes Visitors from ASIS&T

Last week, the ScholCommLab welcomed some smiling new faces to Vancouver. On Friday, Nov 9, attendees of ASIS&T’s 2018 Annual Meeting joined us from Dusseldorf, Detroit, Ottawa, and beyond for a quick lab tour, some dinner and conversation, and one very crowded, very happy selfie.

Last week, the ScholCommLab welcomed some smiling new faces to Vancouver. On Friday, Nov 9, attendees of ASIS&T’s 2018 Annual Meeting joined us from Dusseldorf, Detroit, Ottawa, and beyond for a quick lab tour, some dinner and conversation, and one very crowded, very happy selfie.

At the conference, speakers and attendees from around the globe met in Vancouver to discuss the latest advances in information science. Over the course of the four-day event, delegates heard presentations about new research findings, digital ethics, innovative methodologies, and more. The Annual Meeting was preceded by the well-known Workshop on Information and Scientometric Research (SIG/MET), which featured research by ScholCommLabbers Rodrigo Costas (Visiting Scholar), Juan Pablo Alperin, Fereshteh Didegah, and Stefanie Haustein.

Thanks to everyone who joined us for a fun and thought-provoking evening!

For more information about ASIS&T, visit asist.org.

Open Science Beers YVR

Join us for the next Open Science Beers YVR

Thursday, March 14, 2019

6 PM - 9 PM

The Emerald (555 Gore Ave)

About Open Science Beers YVR

During last year's FORCE11 conference, the idea was born to recreate Montreal’s popular Open Science Beers event right here in our very own Vancouver. Now, that idea has become a reality.

Each month, we’re bringing together friends of Open Science* for a casual evening of drinks and conversation. Tell us about your new project, make a new connection, or simply sit and enjoy your beer/wine/nonalcoholic-beverage-of-choice with like-minded people in a friendly environment.

Of course, like the best Open Science, this event is free (well, other than your bar tab) and open to all.

*and Open Data and Open Education and Open Humanities and Open Source and Open Access and ...

Keep in touch!

Sign up for our mailing list for updates about upcoming #OpenScienceBeersYVR events. We promise, we will ONLY use your details to keep you posted about future meetups.