ScholCommLab to be a “Force” at FORCE2018

Taking place from Oct 11 to 12 in Montreal, QC, FORCE 2018 is a multi-disciplinary conference dedicated to creating a more open future for scholarly communications. This year, the conference will bring together a diverse mix of publishers, librarians, students, and policy makers—as well as several members of the ScholCommLab! Stefanie Haustein, Juan Pablo Alperin, Asura Enkhbayar, Tristan Lamonica, and lab collaborator Erin McKiernan will all be in attendance, and ScholCommLab research will be featured in a total of four talks throughout the event.

“I am excited to have so many of us from the ScholCommLab present at the FORCE conference,” says Alperin, lab co-director. “That so many of our submissions were accepted for presentation is a sign that we are working on issues that are the community is interested in, and, hopefully, that they value.”

In anticipation of this exciting event, the team shares their thoughts on the upcoming conference and the changing nature of scholarly communication.

The theme of this year’s FORCE conference is engagement. What does “engagement” mean to you?

Alperin: This word has different meanings depending on the both the context and the time in which we use them. At this moment, I am completely absorbed in conversations about the need for scholarly communications to be managed from the academy itself. In this sense, I see engagement as the process of getting scholars themselves involved in the ownership and operations of scholarly communications, especially around the infrastructure.

Haustein: When I am thinking about engagement in the context of scholarly communication, I think about how academics or the general public interact with research objects, such as peer-reviewed journal articles. In that context, engagement can be any type of interaction: reading an article's title, downloading the PDF, posting its link on Facebook, citing it in the literature review of another publication, discussing its theory in a blog post or using its method in a new study.

Enkbayar: Some people enter engagements while they're (still) in love, artists and speakers might look for engagements, and countries engage in war too. This word with many different meanings is similarly used ambiguously in science. Researchers engage with each other’s ideas in the writing process, are supposed to be engaging and have societal impact, and also engage with the public themselves. The common theme I am curious about is interaction.

Lamonica: Engagement to me means the fostering of the increasingly important aspect of collaborative research and discussion. It allows researchers to push the status quo by including perspectives and insights from multiple disciplines and areas of study. The more we collaborate, the better our research becomes.

Engagement means going outside the classroom, leaving the lab, to give something back to the community.

McKiernan: For me, engagement means going outside the classroom, leaving the lab, to give something back to the community. Engagement means reaching out beyond academic circles to the public who often finances our research and may benefit from it. And it means listening to the public, to hear what they're interested in and learn how you can help as a teacher and researcher.

How does this theme relate to your talk?

Alperin: I am going to be presenting about the consortium that we helped establish—the Substance Consortium—which brought together groups that share common goals and values: PKP, Erudit, SciELO and eLife. We are all building platforms for scholarly publishing and have a need for an open source online editor (like Google Docs, but open!) that is specific to scholarly works. We have trusted each other in the hopes that our work will build an engaged community that supports this project beyond what we can do ourselves.

Haustein: My talk at FORCE is entitled "Metrics Literacy: Educating Researchers and Research Support Staff Regarding Scholarly Metrics" and presents my new research project, for which I just received seed funding from the University of Ottawa. It relates to engagement in two ways: on the one hand, scholarly metrics are based on engagements, as I describe above. On the other hand, the aim of the Metrics Literacy project is to improve the ways in which people use bibliometric and altmetric indicators by increasing their understanding of how and what they do (and do not) measure.

Enkhbayar: In my talk, I draw a tentative image of a theory of scholarly communication inspired by Ludwig Wittgenstein's philosophy of language. Wittgenstein's later philosophy is known for the emphasis of the social interactions of our very lives. According to him, the meaning of words is in their usage. Similarly, I want to discuss the idea of a meaning of citations (and science itself) which is rooted in our usage of them. I want to contrast this idea to the often cited theory of concept symbols introduced by H.G. Small in 1978.

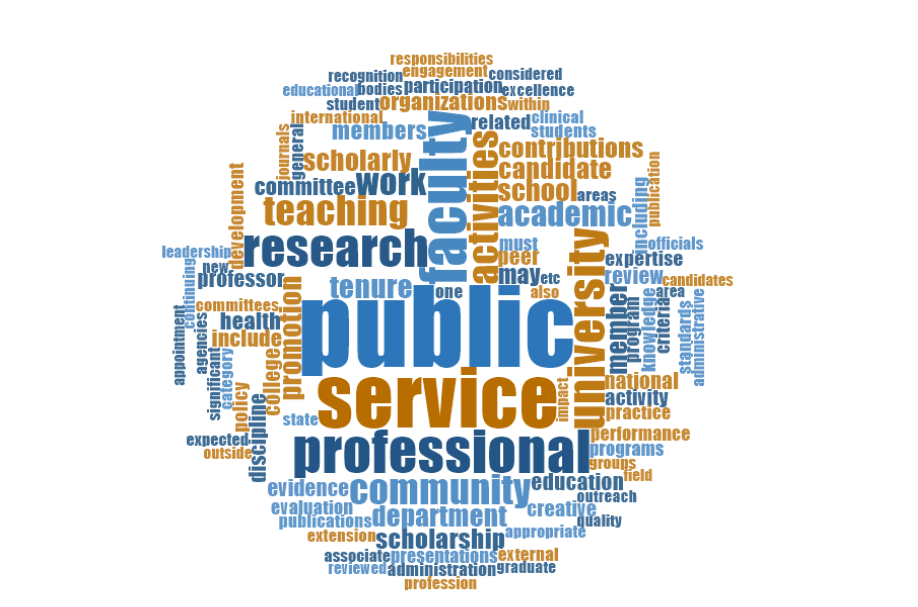

McKiernan: I'll be presenting results of a study we conducted to analyze the content of university review, promotion, and tenure documents. We wanted to learn how the public dimensions of faculty work are incentivized and valued in evaluation processes. Unfortunately, we found that words related to public and community were associated with service—the least valued group of activities.

If you could change one thing about how scholarly information is communicated, shared, and used today, what would it be?

Alperin: Oh, so many things to change, it is impossible to pick one. Instead of shooting high, I will pick the most basic change that I believe we need: Every single piece of scholarship should be freely available to the public. Every piece, without exception. Moreover, authors should not have to pay to publish them (at least not directly). If you'll grant me a second thing to change, I would say that all scholarly communication should be managed and supported by the academic community.

Every single piece of scholarship should be freely available to the public. Every piece, without exception.

Haustein: Ideally, barriers to access scientific knowledge would be removed. This, of course, includes open access to the literature and removing paywalls to content, wherever possible. But I'd also like to see more transparency in academia in general. At the ScholCommLab, we value open science and try to be as open as possible. I am especially looking forward to participate in OpenCon in Toronto this fall to learn more about open education.

Enkhbayar: More interaction and linking! Citing someone shouldn’t mean that you're simply increasing the word count, but actually connecting to a paper, a passage in the text, and most importantly to the author(s).

In a dream world, what would scholarly communication look like?

Lamonica: In a dream world, scholarly communication would be accessible and integrated to a broader public outside of academia. Much of the research being produced is of public interest and incredibly important, but is never disseminated widely for people to consume outside of the usual social bubble.

McKiernan: I think we as academics have to place more importance on sharing and public engagement. In an ideal world, all the results of our research, teaching, and other academic activities would be publicly shared. However, they are many barriers to this, not least of which is the way we are evaluating faculty. We have to reward sharing and public engagement if we want it to be more prevalent.

FORCE2018 takes place from October 11 to 12 in Montreal, QC. For more information and a full list of presentations, visit www.force11.org/meetings/force2018.

Visiting Scholars at the ScholCommLab

The ScholCommLab is pleased to welcome three visiting scholars to Ottawa this fall: Kate Williams, Enrique Orduña Malea, and Rodrigo Costas. Each of these visitors will spend a short stay at the lab, working with the team on a research project of their choosing. The hope is that these partnerships will pave the way for future collaborations, and interesting research in the long term.

“Collaborative research is always better,” says Stefanie Haustein, co-director of the ScholCommLab. “From my own experiences, I’ve learned that research stays are an ideal way to get new projects started.” That’s why we initiated the Visiting Scholar Program, which invites academics from all over the world to join the lab for a collaborative research stay.

“It’s easier to collaborate on a research project after an initial connection has been made,” Haustein explains, “but to really think about, discuss, and develop new ideas, it makes sense to work on things together in the same space.” Haustein says she was lucky enough to do a few research stays herself as a postdoc, which has instilled a strong belief in the power of collaborative research. “I’m still co-authoring and working with many of the people I met through these programs,” she says. “We’re hoping to achieve something similar through our Visiting Scholar Program.”

Kicking off the program, Kate Williams visited the lab from September 20 to 27. Currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Weatherhead Centre, Harvard University, Williams is also an Economic and Social Research Council Future Research Leaders Fellow in the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge and a Research Fellow at Lucy Cavendish College Cambridge. During her time in Ottawa she kicked off a collaboration with the ScholCommLab about the structures and cultures of evaluation in policy research, and how altmetrics might be used to assess the societal, cultural, or economic “impact” of research.

Rodrigo Costas, a senior researcher at the Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) at Leiden University, will join the lab from Oct 5 to 16. Costas, who holds a PhD in Library and Information Science from the CSIC in Spain, leads the research line in ‘altmetrics’ at CWTS, where he focuses on developing new theoretical and analytical approaches to study the interactions between social media and science. Costas has been collaborating with members of the ScholCommLab for many years, and the team looks forward to continuing and strengthening that relationship this October.

Finally, Enrique Orduña Malea will complete a longer research stay from October 1 to 26. Malea is a Technical Telecommunication Engineer and an Assistant Professor at the Polytechnic University of Valencia (UPV) in the Department of Audiovisual Communication, Documentation and History of Art (DCADHA). His main research lines are focused on Web Scientometrics, the analysis of Science and its main agents through the Web.

The ScholCommLab is thrilled to welcome these three distinguished scholars to the lab this fall, and to continue the Visiting Scholar Program with several new faces in the new year.

To find out more about the Visiting Scholar Program, visit scholcommlab.ca/join-us/visiting-scholar-program.

Now Available: Results from the Review, Promotion, and Tenure Study

The review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) process is one of the cornerstones of academic life, influencing how and where faculty focus their attention, direct their research, and publish their work. In a recent study, the ScholCommLab analyzed this process from a new perspective—textual analysis of a representative sample of RPT guideline and policy documents—to understand the incentive structures that reinforce traditional publishing practices and the use of citation-based metrics at the expense of publicly oriented scholarship.

Our full results are available at Humanities Commons, and have also been profiled in Nature, Inside Higher Ed, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. But we're sharing some of the key findings right here on the ScholCommLab blog.

Key Takeaways from the RPT Study

- 75% of research intensive institutions mention citation metrics

- 90-95% of all institutions, across institution types and disciplines, mention traditional research outputs (e.g., articles, book chapters, conference presentations, etc.)

- 75% of all institutions mention the term "public", but only 64% mention the concept of "public and/or community engagement"

- Life sciences are more concerned with "Impact" and "Community Engagement" than the other disciplines; Physical sciences and Math are more concerned with citation metrics (Social Science and Humanities, which are the least)

- The words surrounding mentions of "public" emphasize that working for the public is a service activity; words surrounding "community" emphasize that it is the academic community that is of primary concern

Overall, we conclude that while universities speak about their desire for public engagement in broad terms, they give faculty few specifics on how pursuing public scholarship, including publishing in open access journals will be recognized in their career progression. It seems that, "in order to be successful, faculty are mostly incentivized towards research activities that can be counted and assessed within established academic conventions."

For more information about the study, visit scholcommlab.ca/research/rpt-project or read up on the latest media coverage at scholcommlab.ca/media.

Q&A with Asura Enkhbayar: Looking Ahead to STI 2018

How do we measure the impact of research? And how can we learn to do it better?

From September 12 to 14, the ScholCommLab’s Asura Enkhbayar will attend STI 2018, an international bibliometrics and scientiometrics conference dedicated to answering these questions. Hosted by the Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) at Leiden University in collaboration with the European Network of Indicator Developers (ENID), the conference will cover a diverse array of topics from reproducibility in scientometrics to evaluation of open scholarship and everything in between.

Here, Enkhbayar tells us more about the conference, the research he’ll be presenting, and what he’s most looking forward to about visiting the beautiful city of Leiden.

Tell me about STI. What’s the focus of the conference?

Tell me about STI. What’s the focus of the conference?

The STI is the biggest conference for scientiometricians and bibliometricians. We are attending especially because of the track dedicated to challenges of social media data for bibliometrics.

The theme of this year’s conference is “indicators in transition” and their role in driving more comprehensive, socially oriented forms of Science, Technology and Innovation evaluation. What, in your opinion, are some of the most important “indicators in transition” we’re seeing today?

That’s a big question! Well, I guess it’s the big question that everyone’s trying to answer at the moment. There’s a large demand for—I’ll just put it this way—better indicators, because people are spotting problems with the current status quo.

Some years ago, the big focus in this field was altmetrics, which is supposedly a better indicator of social impact. But, now, with all the big developments in social media and digital communication, people are critically investigating the nature of many new indicators. It’s an ongoing development, and I feel like there’s a new critical perspective coming into play, which is being emphasized more and more in research. I think that’s a great thing.

So I have no concrete answer for you, just support for the questions around new indicators that researchers are starting to ask.

You’ll be presenting some work you did with the ScholCommLab about Facebook metrics. Can you tell me, briefly, what it was about and how it fits with STI?

It was an obvious choice to submit our paper to the STI this year. The conference, and its focus on technical challenges, is a perfect fit for the research I’ve been doing with Juan Pablo Alperin at the lab. In our study, we looked at Facebook as a data source for scientometrics. We wanted to figure out, in the beginning, how different approaches for collecting engagement data would influence the results of various the collected metrics. But in the process of doing this research, we uncovered a number of technical challenges within altmetrics that make this kind of work difficult. We realized that a very big chunk of the work we had to do was about fundamental technicalities that needed to be figured out in order to get to reliable data. We ended up investigating some of those challenges instead.

So what was supposed to be a quick project turned out to be months of work on technical details related to the general structure of the web and scientific publishing, but also to Facebook’s internal algorithms, which are still a black box for us.

"What was supposed to be a quick project turned out to be months of work on technical details related to the general structure of the web and scientific publishing, but also to Facebook’s internal algorithms, which are still a black box for us."

So Facebook data could have the potential to be a really good indicator, but all of these technical issues are getting in the way?

In this particular approach, yes. As always, it depends on many things, but it’s important to figure out these details before using any new indicator. This is still a work in progress, but we are trying to answer the question: How much do these technicalities affect the outcomes? I think it’s a very essential question to address, if one uses Facebook as a data source.

So the next step in your research will be to investigate and understand whether, or to what degree, these technical difficulties affect the outcomes of research that relies on Facebook data?

Exactly. We have now finished the first part of the project, and we’re finally starting to look into the questions that we were initially hoping to answer. We’ve been sidetracked for a long time—well, more than sidetracked, because the challenges that came up were really important—but I’m looking forward to taking this research further.

What are you most excited about seeing or doing at the conference?

I’m really looking forward to some of the presentations about the exact same topic we’ve been investigating, to figure out what other people are doing to overcome these challenges. Because I think these are questions that have been surfacing for many researchers recently.

But obviously, the conference is bigger and broader than that. I recently attended the CWTS summer school on scientometrics, so I’ve had my first overview and introduction to the field. Now that I have this formal education to build off of, I’m really looking forward to learning more about some of the research that’s being done in this area: seeing the projects and the people doing the work, and really getting a sense of what’s going on in the field.

Let’s end with one fun question: is there anything you’re really looking forward to doing in the lovely city of Leiden?

I guess what I want to do is go on a proper pub crawl: finding a few bars, trying a few beers. The first time I was there, I didn’t know the city, I didn’t know the people. But now that I’ve already been there once, I feel like I’m familiar with the basics of the city. This time, it will be different. This time I’m ready.

For more information about the conference, visit sti2018.cwts.nl. Read more about Enkhbayar’s research at arXiv.org.

President's Dream Colloquium on Making Knowledge Public

How is public policy shaped by research? How is the public already actively involved in science? How is research and scholarship taken up by the public?

In today’s climate, it is more important than ever for universities and researchers to assert themselves in the public sphere in more purposeful ways. The President's Dream Colloquium on Making Knowledge Public is part of that effort.

A collaboration between SFU Graduate Studies, the Publishing Program, Public Knowledge Project, and the ScholCommLab, this colloquium seeks to create a conversation between the SFU community and the citizens of Metro Vancouver on the value of university-based research. Through public lectures, readings, and discussions, it will offer a broad overview of the ways in which research makes its way into society, providing a unique opportunity to gain exposure to a cross-disciplinary network of academics, citizen scholars and government officials.

Confirmed Speakers

Most lectures will take place at SFU's Burnaby campus, a couple of lectures taking place at SFU Vancouver. There will be a reception and networking session following each talk.

- Jevin West, Co-creator of Calling Bullshit Course, University of Washington, Calling Bullshit on Fake News.

Thursday, September 13, 5:30–7 pm, reception to follow, SFU Vancouver. - Mario Pinto, President of Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Knowledge Sharing and Social Responsibility.

October 1, 5:30–7 pm, reception to follow, SFU Burnaby. - John Borrows, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law, Collaborating with Indigenous Communities in Research.

Wednesday, October 10, 5:30–7 pm, reception to follow, SFU Burnaby. - Shannon Dosemagen, Executive Director of the Public Lab, Citizen Science.

Thursday, October 25, 5:30–7 pm, reception to follow, SFU Burnaby. - Hebe Vessuri, social anthropologist, Global Participation in Knowledge Production.

Thursday, November 8, 5:30–7 pm, reception to follow, SFU Burnaby. - Robin DeRosa, Professor and Director of Interdisciplinary Studies at Plymouth State University, The Future of Public Mission of Universities.

Thursday, November 22, 5:30–7 pm, reception to follow, SFU Burnaby.

Making Knowledge Public is both a public speaker series with leading thinkers and a graduate seminar course open to students from the across the university. For more information, or to register, visit the SFU website.

Highlights from the Brazilian Meeting on Bibliometrics and Scientometrics

This July, ScholCommLab’s Stefanie Haustein attended the sixth ever Brazilian Meeting on Bibliometrics and Scientometrics in Rio de Janeiro. In this short Q&A, she shares highlights from the event, including a keynote presentation about her work on Twitter and scholarly communication, connections with researchers from around the world, and a healthy dose of delicious Brazilian cocktails.

Tell me about the Brazilian Meeting on Bibliometrics and Scientometrics. What’s the conference about? Who attends?

Tell me about the Brazilian Meeting on Bibliometrics and Scientometrics. What’s the conference about? Who attends?

The EBBC is a biannual national conference, where researchers and students from all over Brazil meet to present and discuss their findings on bibliometric and altmetrics research. This year was the sixth time EBBC took place, and it returned to Rio de Janeiro, where the inaugural conference was held in 2008. The conference language is Portuguese with guest speakers presenting in English. I was quite impressed by the number of presentations and the size of the Brazilian scholarly metrics community.

The theme of this year’s conference was “Science in Network.” In your view, how do networks affect or enable the way research is done?

Networks are essential to do research. We’ve come a long way from the lone scholar and most research now is carried out by groups of scholars, which often involve national and international partners. I personally think that any analysis or publication gets better when it is done in collaboration, particularly if collaborators come from different backgrounds and are equipped with different skill sets.

You gave one of the keynote speech at the conference. Can you tell me, briefly, what it was about? Did your work at the ScholCommLab inform your talk?

EBBC invited three international speakers. Cassidy Sugimoto opened the workshop on Tuesday with a talk on science in a global society. Cameron Neylon and I presented on Wednesday. My talk was entitled How, when and what does the Twittersphere tweet about science? and summarized findings from my work on scholarly Twitter metrics. It was based on this book chapter (which I also blogged about here) and provided data on tweets linking to scientific articles published by Brazilian authors. Having cleaned geographical data for all tweets from Brazil (with a view of Copacabana), I could show that the majority of tweets came from the South and Southeast of Brazil, where most large cities are located. For the first time I also analyzed emojis used in those tweets. Juan Alperin helped me to extract those from the tweet text using an emoji Python library. At less than 1%, only a small share of tweets contained emojis, but it was nevertheless interesting to explore differences between countries.

What was the highlight of the conference for you?

The whole week was a highlight so it is hard for me to pick one. Since I do not speak Portuguese I probably missed a lot of interesting talks by local presenters, but I had really interesting discussions over coffee during breaks and over caipirinhas during a social event in a salsa bar. I particularly enjoyed meeting people in person who I had previously been connected to on Twitter, sometimes for years. I also managed to take a day off to go snorkeling in Búzios.

What did you take away from the event?

I made a number of new connections at EBBC6, which will hopefully lead to new collaborations and might even bring new visiting scholars to the ScholCommLab. After Germana Barata left SFU last month, it would be great to have another scholar from Brazil come work with us!

I also came home from Rio with a concrete plan to publish the results from the Brazilian Twitter analysis together with Iara Vidal and Fábio Castro Gouveia on the Scielo blog. I am pretty excited about the potential audience, as the blog publishes all posts in English, Portuguese, and Spanish.

For more information about the conference, visit ebbc.inf.br.

Preview: David Moscrop at TEDxYYC

Why do we make bad political decisions, and how do we make better ones?

On Thursday, June 21, ScholCommLabber David Moscrop will unpack these questions and more on the TEDxYYC stage. Drawing from his own and others’ research, as well as from his personal experiences as a media commentator, he’ll examine the way our current democratic system functions—or, rather, dysfunctions—and how it could be improved in the future.

To give you a taste of what to expect, we chatted with Moscrop about his upcoming talk, the research that informed it, and the struggles of not swearing on live TV.

The theme of your upcoming TEDx talk is “Are we too dumb for democracy?” What got you interested in this topic?

Years ago I came across a book by the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, who wrote that social scientists need to understand brain and behaviour to improve people's lives. That was enough for me. I look at a lot of research and wonder what the point is. Maybe it'll go somewhere, maybe it won't. And I get why we need to support research wherever it may go, but I like to try to direct mine as much as I can towards producing something that will improve some bit of someone's life. So, I wanted to know whether and how we could make decisions individually and collectively that empower people to get what they want based on rationality and autonomy rather than buried impulses and whatever they’ve been manipulated into thinking they wanted—whether by politicians or business interests or whomever.

You’re about to publish some very exciting research about political pundits and how—or perhaps whether—they share knowledge online. How will this work inform your talk?

Part of making a good political decision is having good, reliable information. And trustworthy information. Today, more than ever, there are a lot of false or misleading “facts” out there. A lot. So knowing that sometimes pundits rely on good academic information and share it with the public is encouraging, even if they don't do it nearly often enough. I'll be calling for more of that. The future of good political decision making is partly contingent on researchers being able to circulate their work. I'm slightly encouraged to see a new generation of publicly engaged scholars emerging. I hope to see more.

You’re an academic, but you’re also a journalist and a media commentator. How do you see your role(s) as a communicator?

I try to use my training to help give people some context for what's going on and perhaps even some tools to think critically about who's trying to get what and from whom. I also try to share research and amplify the work of others. So, basically, I’m a loudspeaker. I try to be accessible with my work and, to the extent that it's possible, entertaining. You educate folks while also entertaining them if you have the guts to loosen your collar for a few minutes. It helps that I don't care if I ever get a permanent academic job, because I can say whatever I want without too much concern.

"I try to be accessible with my work and, to the extent that it's possible, entertaining. You educate folks while also entertaining them if you have the guts to loosen your collar for a few minutes."

Do you consider yourself to be a political pundit?

For better or for worse, technically that's what I am! It's a fun gig. I get to share my thoughts with the world and get paid for it. Then I get criticized and even name-called by anonymous bozos, which always reveals something about the human condition. But best of all, the gig forces me to be clear and concise and real, which is something many academics could learn to do better.

Not that you asked, but for what it's worth, the hardest part of the job is not swearing on live TV or radio. With the current state of things, I'm always a syllable away from saying something I’d regret.

What do you hope to leave TEDx audiences with?

Very simply: You can—or perhaps "You can"—make good political decisions, and it's important that you do, since the future of democracy may depend upon it. Now, let's have a good old chat about how individuals can get better at that, and how governments can and must support these efforts by offering opportunities for meaningful engagement that produce outcomes that matter.

David Moscrop’s talk takes place on Thursday, June 21, 2018. For more information, visit the TEDxYYC website.

Stefanie Haustein on the Altmetric Blog

Starting this week, ScholCommLab co-director Stefanie Haustein is publishing a series of guest posts on the Altmetric Blog about the role of Twitter in scholarly communication. Read on for a small taste of what to expect, and find the whole series at at altmetric.com/blog/.

It’s almost been a decade since altmetrics and social media-based metrics were introduced. Since those early days they have been heralded as indicators of the societal impact of research—after all we all like, comment and share things on social media. An early study had seen tweets to predict citation impact shortly after an article was published, which got hopes up that Twitter activity could serve as an early indicator of research impact. However, the analysis was soon followed by several large-scale correlation studies, which showed that there is hardly any connection between tweet and citation counts. But other than proving that Twitter activity did not measure the same type of impact as those reflected by citations, low correlations did not help to understand what tweets linking to scholarly publications did actually measure.

It’s almost been a decade since altmetrics and social media-based metrics were introduced. Since those early days they have been heralded as indicators of the societal impact of research—after all we all like, comment and share things on social media. An early study had seen tweets to predict citation impact shortly after an article was published, which got hopes up that Twitter activity could serve as an early indicator of research impact. However, the analysis was soon followed by several large-scale correlation studies, which showed that there is hardly any connection between tweet and citation counts. But other than proving that Twitter activity did not measure the same type of impact as those reflected by citations, low correlations did not help to understand what tweets linking to scholarly publications did actually measure.

This mini series on scholarly Twitter metrics, to be published on the Altmetric blog over the next five weeks, will explore the What,Where, How, When and Who of academic Twitter, to shed some light on the significance of tweets in the context of social media metrics. The blog posts are based on a book chapter [1] for the Handbook of Quantitative Science and Technology Indicators edited by Wolfgang Glänzel, Henk Moed, Ulrich Schmoch and Mike Thelwall, which will be published later this year. A preprint of the chapter is available on arXiv.

[1] The blog posts focus on the two datasets used in the chapter: all 24 million tweets captured by Altmetric and a subset of 3.9 million tweets linking to papers published 2012 and covered by the Web of Science. For detailed descriptions of methods and related literature refer to the chapter.

Preliminary Findings from the Review, Promotion, and Tenure Study

Support for the open access movement has grown in recent years, and today more than a quarter of scholarly literature is freely available. Yet, despite years of advocacy work and countless policies and mandates promoting openness, the majority of researchers are still not compelled to make their research outputs publicly available. Why is this the case? What barriers stand in the way of creating real change?

In a study by the ScholCommLab, Juan Pablo Alperin, Carol Muñoz Nieves, Lesley Schimanski, Erin McKiernan, and Meredith Niles suggest one possible explanation: the state of the review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) protocols at today’s research institutions. These documents, which are meant to provide faculty with the guidelines needed to achieve career success, are among the key incentive structures that drive their research dissemination strategies. But as the team’s findings reveal, surprisingly few of them mention open access at all—and even fewer provide the tools needed to pursue it.

In this interview, the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Alperin, shares some of the preliminary results and what they could mean for the future of scholarly research.

Tell me a bit about the study. What did you investigate and where are you at now?

We’ve recently finished the first phase of the research: we collected more than 850 RPT guidelines from colleges and universities across the United States and Canada and assessed the degree to which they included guidelines specific to open access, research metrics, and forms of research dissemination. Basically, we found that only about 5% of the institutions studied made explicit mention of open access in their guidelines, and, in several of those few cases, the mention was done to call attention to the potential problematic nature of these journals, which are sometimes incorrectly seen as being of lower quality than subscription journals. We have submitted a comprehensive literature review of these issues for publication, and are about to submit another manuscript with these and other results. While we wait for these to come out, we have published the dataset containing the analysis of terms and concepts. We’ve also started a second phase in which we will survey faculty at each of the institutions in our study to find out more about their perceptions of the guidelines and how they use them to inform their work.

Why did you decide to study RPT guidelines? How do they factor into the question of openness?

We spend a lot of time at events related to open access and scholarly communications and it seemed that everywhere we went the role of incentives kept coming up as the biggest barrier to openness. Since the RPT process is one of the places where these incentives are formalized, it made sense to study them. As we did a review of the literature, we found that people at every level of universities—faculty, deans, and vice provosts—have all called for changes in the process to incentivize different forms of scholarship.

"People at every level of universities—faculty, deans, and vice provosts—have all called for changes in the process to incentivize different forms of scholarship."

Are you surprised by what you found so far?

I was surprised to see that mentions of “open access” were almost non-existent. We knew we weren’t going to find it everywhere, but to find it mentioned by only six institutions out of a hundred-and-twenty-something? And to see that most of mentions only discussed open access as a word of caution against predatory and low quality publishing? That was disappointing. It shows that there’s room to do better.

Another thing that surprised me was how little the term “impact factor” was mentioned in the documents. In the open access world, we talk about the impact factor as acting like a sort of boogieman, but in our study, we found that the actual term was used by only 20% of the institutions—much less than you would think given how often it is discussed as the source of all research evaluation problems. It was unsurprising, however, to see that it was present in a higher proportion of documents from research-intensive institutions (the so-called “R-types”), where it appeared in about one third of the documents. This shows us that we need to be cautious of how the discourse of research-intensive universities dominates our thinking about incentive structures across all institutions.

Although impact factor was not so pervasive, words related to metrics (such as citations, h-index, rejection rates) appeared a little more often—in the documents of almost half the institutions. Again, this varied by institution type, with metrics being mentioned in almost three quarters of those R-type institutions. Similarly, we found them to be much more present in the documents of physical science and mathematics departments than in those of the social sciences and humanities.

So, while it was not surprising to see the RPT documents of research-intensive institutions and physical sciences and math departments included more mentions of impact factors and metrics than others, we were surprised to see the extent to which this difference dominates the narrative across the board.

Tell me a bit more about the second phase of the study. What do you hope to achieve in the coming months?

It’s still unclear to what extent people are actually using these documents to make decisions around what they should do for their career. After spending a lot of time with these documents, we have a sense that there’s a lot of culture that happens around them, rather than in the documents themselves. That’s why we’re doing the second part of the study.

"After spending a lot of time with these documents, we have a sense that there's a lot of culture that happen around them, rather than in the documents themselves. That's why we're doing the second part of the study."

The documents use a lot of vague language that allows for many different interpretations, including a large majority that mention the words “public” and “community”. At the same time, around 90% of them specifically mention peer review, concrete output types like articles and books, and publication venues like journals and university presses. So, while the documents leave room for interpretation when it comes to openness, they also provide specifics around traditional output types. We know from everything we hear day to day, as well as from the literature, that researchers still don’t feel they should be more open or more public. So we’re trying to better understand people’s relationships to the documents: Are they using them as guides? Are they really consulting them?

Are all aspects of the guidelines pretty vague? Or just the parts that discuss openness?

This is the part that’s interesting. The trifecta that normally gets valued in the RPT process is teaching, research, and service. But it’s known, both in the literature and in what we hear anecdotally, that research is really the core.

We’ve been analyzing and looking for the presence of terms like “public,” “community,” and “quality,” and we found them used in a very large percentage of the documents. But when we looked at the words around them, we found that they’re nonspecific qualifiers, words like “significant”, “substantial”, “demonstrable”. The guidelines have nonspecifics around what openness looks like. But the documents do have specifics around research outputs, around how to succeed in that realm. We see terms like “article,” “book,” and “refereed,” specific terms that guide what research should look like.

"The trifecta that normally gets valued in the RPT process is teaching, research, and service. But it’s known, both in the literature and in what we hear anecdotally, that research is really the core."

But isn’t the number of research institutions with open access policies increasing? Where is that support actually playing out, then, if not within the RPT protocols themselves?

This is another reason why we thought it was important to tackle incentives. There has been an uptick in the number of universities with open access policies. But even still, there’s been little uptake among researchers. They don’t really see the value of openness yet, or they don’t prioritize it. To me, that means something else needs to change. Policies alone may not be enough. Tackling incentives might be a way of pushing academics to really think about these issues.

So where does this leave us? What’s next for you?

I want our research to inform conversations and actions about shifting the way we value open research and public engagement for greater openness. I’m hoping that our work can provide some evidence for the vice presidents, provosts, deans, and faculty who feel incentives are impeding change. I want it to provide the information that’s needed to make effective change happen. That is, I want to see this work being taken up by the people who are trying to make a difference.

Want to learn more about the RPT project? Data from the study can be found at Harvard Dataverse and a preprint is available at Humanities Commons. Or, sign up for our newsletter for ScholCommLab news, research updates, and more.

Key Takeaways from RightsCon Toronto 2018

From May 16 to 18, the ScholCommLab’s Research Associate Dr. Katherine Reilly and Carol Muñoz Nieves attended RightsCon Toronto, an international event that brought together policy makers, human rights advocates, business leaders, scholars, and others to tackle leading human rights issues in the digital age.

Reilly and Muñoz are collaborating with researchers from across the world in an ambitious project titled “Policy Frameworks for Digital Platforms: Moving from Openness to Inclusion". Coordinated by the NGO IT for Change and funded by IDRC, the project aims to investigate some of the most pressing questions around the platform economy. At this year’s RightsCon, Reilly joined researchers from Brazil and India in a thought-provoking panel titled "Platform Politick: Redefining Digital Rights for the Platform Generation".

Throughout the session, panelists examined the multiple economic and social impacts of platformization—from labor rights and consumer privacy to equitable trade for countries at the margins of capitalism—and what they mean for the larger questions of openness, diversity and inclusion. By exploring the bigger picture of the political economy of digital rights in the platform economy, this panel stood out from others at the conference, many of which were focused on how to secure the privacy of individuals through legal and technological processes.

For those who missed it, we’re sharing some of the key highlights from the talk, right here on the ScholCommLab blog:

- Reilly discussed her research about goods sharing platforms in Vancouver, BC. Along with Muñoz, she is investigating what type of data these platforms are gathering and how their use of the data could influence the marketplace—a primary social justice concern associated with this new digital economy. She also spoke to the complexity of the policy landscape and how best to regulate platforms that intermediate transactions in the marketplace.

- The presenter from the Brazil-based project, Mariana Valente, discussed her team’s work with Netflix. The second country to adopt Netflix, Brazil is currently the 8th largest market for the platform worldwide, presenting major concerns about access to content, cultural diversity, and regulation. Valente explained that Netflix does not currently pay the same taxes as other media companies and proposed some ideas for how to better regulate the platform, as well as how to enable more inclusion of Brazilian content.

- Finally, India-based investigator Deepti Bharthur shared her team’s work on the platformization of agriculture in her home country. Rather than studying at platforms themselves, Barthur’s research aims to understand platformization as a process that transforms cultural environments and markets. Specifically, her team is investigating the value chain of agriculture. On one end of the value chain, India has seen immense growth of agri-tech platforms; on the other, the country is experiencing a rise in platform-based services for consumption, such as online grocery shopping.

For more information about the RightsCon Summit Series, visit rightscon.org.