Three questions with…. DeDe!

Our lab is growing! In our Three Questions series, we're profiling each of our members and the amazing work they're doing—starting with DeDe Dawson. An Associate Librarian at the University of Saskatchewan, DeDe is a visiting scholar with the lab who is passionate about scholarly communication, open access, and advocating for a transition to more equitable and sustainable journal publishing models.

In this post, she tells us a bit about what she's up to—within and outside of the lab.

Q#1 What are you working on at the lab?

I am working with Juan on further analyses of the data from the review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) project. In an earlier phase of the project, the team surveyed more than 300 faculty members across the US and Canada about their perceptions of the RPT process, and what motivates them to publish their work in some venues over others. When reviewing the open-ended questions on that survey, we noticed some interesting responses to a question about what other things (besides the typical triumvirate of research, teaching, and service) are considered in RPT processes. Many people said collegiality was a factor!

We were really surprised by this and found that there is quite a debate in the literature about whether collegiality should be considered in RPT processes. Some scholars have even proposed that it should be a fourth criterion after research, teaching, and service, but the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) strongly advises against this. We decided to analyze the RPT dataset to see the extent to which the concept of collegiality (and related terms, like professionalism and citizenship) are present in documents related to the RPT process. We are currently in the final stages of analysis and writing up our results.

Q#2 Tell us about a recent paper, presentation, or project you’re proud of.

I just finished a two-phase, multi-year project with two colleagues looking at how academic libraries in Canada communicate to their campus communities about big deal journal cancellations. Many libraries have had years of flat or declining budgets, this combined with the hyperinflationary pricing of journal packages means that libraries are having to make major collections cancellations now. It is challenging to communicate this effectively so that faculty and students understand the complex situation and support the library in making these decisions. A paper on our findings has recently been accepted in College & Research Libraries! It will come out in the January 2021 issue, but, in the meantime, you can read the postprint here.

Q#3 What’s the best (or worst) piece of advice you’ve ever received?

I have a mug that says “Sometimes all you need is a good book and a cup of tea”—so true! I would only add “and a purring kitty on your lap.”

Find DeDe on Twitter at @dededawson.

Managing research data: A beginner's guide

Data management is a core aspect of the research process, helping scholars organize their work, share it with others, and collaborate effectively. But data management often comes as an afterthought in the research process, perhaps because so few researchers receive formal training in how to do it. As Canada’s national funding bodies prepare to launch a new policy “promoting sound data management and data stewardship practices,” federally funded grant holders are going to have to brush up on their data management skills—and brush up fast.

“You essentially won't get funding if your research proposal doesn't address how you will be storing and managing your data,” says Lina Harper, a student policy analyst at the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and a researcher on the ScholCommLab’s Meaningful Data Counts (MDC) project. “Also, it’s tied to the larger trend of open science—opening and publishing your data means that your work can be verified, and that your scientific output is transparent and reproducible. If you want to be a researcher and a scholar, then research data management is going to be your new reality.”

But what should a research data management plan actually look like? And what does it take to create one? In this post, Lina offers guidance from her own experiences crafting a Research Data Management Plan (RDMP) for the MDC project, as well her master’s research on digital humanities scholars and their data reuse practices.

What is a Research Data Management Plan?

“The Research Data Management Plan is a relatively new product in the scholarly research landscape,” Lina explains. “We're still taking baby steps, especially the Canadian community.” The novelty of this product—as well as the wide range of data collection methods and research practices that scholars use—means that RDMPs can take many shapes and forms. At the core of any RDMP, however, are two basic components: research data, “the data that researchers collect as they embark on scholarly research,” and management, “the process of making your research data transparent and reproducible.” Simply put, an RDMP is a document that helps researchers navigate that process by addressing the key ethical, legal, and technical considerations involved in their project.

To create an RDMP, researchers must think through questions like: What kind of data will we collect? Where will we store it? How will we coordinate as a team? Do we have permissions to access all of the resources we’ll need? By laying out a clear plan for how to tackle these and other potential hurdles in the research process, RDMPs give research teams a common language and shared strategy for ensuring their project will succeed.

While this may sound like a lot of additional work, Lina says many of these steps likely already take place informally in most research projects. “The RDMP verbalizes what's already in your head, the conversations that you are having internally with the PIs, the co-PIs, the research associates,” Lina explains. “In French we say concrétiser—it’s what makes something tangible, translates the knowledge from your brain to a record."

“The RDMP verbalizes what's already in your head, the conversations that you are having internally with the PIs, the co-PIs, the research associates... In French we say concrétiser—it’s what makes something tangible, translates the knowledge from your brain to a record."

Lina Harper

Why Research Data Management Plans matter

At the most basic level, RDMPs help researchers stay organized and coordinated throughout the research process. By laying out a clear plan of action, they make it possible to address potential challenges and snags before they come up, and ensure that project work flows are organized in a way that will work well for the entire team. But RDMPs, Lina says, offer other important benefits too.

First, RDMPs provide a clear outline of how research data was collected, manipulated, and stored. This information—when paired with open scholarship practices, like open data—makes it possible for peer reviewers and other researchers to evaluate study findings. “Especially given ongoing concerns about research replicability, making data easy to access and use is a step in the right direction,” Lina says.

In addition, any good RDMP will include a strategy for how to maintain data in the long term, which can help other scholars build on and extend earlier work. Studies have found that secondary analyses of existing data are becoming more common, offering new insights into important issues like health and poverty. “There’s lots of evidence that data sharing and open access and open data are good things,” Lina says. “Even just taking a slightly different perspective or asking a different research question using the same data can reveal interesting new things.” Creating an RDMP is an important first step towards making that possible.

How to create your first Research Data Management Plan

So what does it take to craft a strong RDMP? Here are a few tips to point you in the right direction:

Tip #1. Talk to your librarian!

“Never underestimate the awesomeness of your library or your scholarly data librarian,” Lina says. These highly specialized librarians are experts in all aspects of data management, and can be a rich resource as you create your RDMP.

Data librarians can go by different names and titles, like Data Services Librarian, Scholarly Communications Librarian, Research Data Management Librarian, or Data Librarian. If you’re at a university, there will likely be a library staff member with one of these titles who can support you. But there are other options too: “If you don't have one at your library, go on Twitter and reach out,” says Lina. “There's a community of librarians who are excited about open science and good research data management. They are passionate about accessibility, transparency, and data reuse — and they want to talk about it.”

“There's a community of librarians who are excited about open science and good research data management. They are passionate about accessibility, transparency, and data reuse — and they want to talk about it.”

Lina Harper

Tip #2. See data management as core to your project

“As a researcher, whether PI, co-PI or a research assistant, you should try to view the RDMP planning process as part of your overall project management,” says Lina. “Start thinking about it on day one.” By considering data management questions at the outset of your project, you’ll be better positioned for success at every other stage, from writing up the methods to publishing the paper. Plus, it means you’ll have more time to work through potential data management challenges, rather than having to troubleshoot in the middle of your study.

For the Meaningful Data Counts project, the RDMP was built into the larger project plan from the beginning. The research team met regularly to work on the RDMP together, with all members sharing responsibility in chairing and organizing meetings and writing the document collaboratively. Throughout, Lina worked closely on developing DMP sections with another research assistant, Erica Morissette, with feedback from PI Stefanie Haustein, Co-PI Isabella Peters, and collaborator Felicity Tayler, the University of Ottawa's RDM Librarian. Felicity's expertise and editorial guidance helped ensure that the RDMP would be useful to the project team, and also be recognized and promoted as a DMP Exemplar in the national RDM training resources published by the Portage Network.

Tip #3. Plan for the long run

Lina emphasizes the importance of considering succession plans as you craft your RDMP. Who’s going to take over the data management if the lead researcher is no longer able to do so? What happens if the team member overseeing data collection leaves academia, becomes ill, or passes away? “It's a hard question to ask yourself or to ask others,” Lina says. “But you might want to think about it. Your data is part of your legacy as a scholar.”

“Your data is part of your legacy as a scholar.”

Lina Harper

Tip #4. Edit collaboratively and iteratively

“Find a way to collaborate on the same document,” says Lina. “Don't do too much versioning—labelling drafts v1, v2, and v3—because you'll get bogged down. People will have the wrong link to the document, and things will get lost.”

Using version control resources, like the UCSD Library’s Version Control Guide, can help not only for the RDMP but also for managing versions of research data itself, especially when paired with clear communication channels. For the MDC project, the team used Google Docs to craft their RDMP. This mode of communication, along with web meetings and quick questions over Slack, allowed them to collaborate and make changes to their plan with minimal coordination effort. Following the team's open science approach, the RDMP is now published on Zenodo, so that other researchers can reuse and remix it.

Working in a collaborative workspace also helped the team see their plan as a “living document” rather than a static resource. “You're going to have to be revisiting the plan all the time,” Lina explains. Maybe your data storage platform changes its terms and services, or you end up collecting a form of data you haven’t planned for. Using a document editing software that allows for continuous change can help your team pivot quickly.

Tip #5. Break it down into smaller chunks and use existing templates

“Take it step by step,” Lina suggests. “While we were working on our RDMP, both me and the other research assistant had full-time jobs, during a pandemic. We just had to take it slowly and work on it bit by bit.”

Ideally, your plan should include the following sections: Responsibilities and Resources, Data Collection, Documentation and Metadata, Storage and Backup, Data Sharing and Reuse, and Ethical and Legal Compliance. Tackling each one in turn is a simple way to make the workload more manageable—especially if you have help: “People think it's going to be a ton of work, but there are so many wizards and DMP assistants out there that prompt you about the sections.” While there are lots of options to choose from, free resources like Portage's DMP Assistant and the DCC's Curation Lifecycle Model are a good starting place.

Tip #6. Make it fun

Finally, remember that you’ll likely be referencing this plan for months, years, or even decades to come. Put the time in to make it appealing and easy to use. Your entire team will thank you for it.

“Put things into tables, use different colors, make it jazzy.” Lina suggests. “Format it well, so that when you look at it, it looks nice. Your plan should make you feel excited about your project—whatever that looks like to you.”

“Your plan should make you feel excited about your project—whatever that looks like to you.”

Lina Harper

A last word on research data management

Of course, managing research data efficiently and ethically is a complex process—one that will look different for every project. The tips in this post are just a few recommendations that helped the MDC team create their RDMP, but there are many, many more. For other suggestions (and helpful examples), you can download the team's plan on Zenodo, check out the Portage Network’s list of Tools and Resources, or reach out to your institution’s RDM specialist.

Learn more about the Meaningful Data Counts project at the ScholCommLab website.

Stefanie Haustein wins uOttawa Library Open Scholarship Award

“I am convinced that openness and transparency make research outputs and outcomes better,” says Stefanie Haustein when asked what motivates her to practice open scholarship. “Knowledge produced by the scholarly community should be open to all, not hidden behind paywalls.”

The ScholCommLab co-director has been practising open research just after finishing her PhD, when she began posting her journal articles on arXiv and publishing in gold OA journals such as PLOS ONE. Since then, she’s incorporated more and more openness into her work, both in her research and in her teaching as an assistant professor at the School of Information Studies at the University of Ottawa. Last winter, Stefanie’s students produced and shared their own online educational resources on information literacy, which have collectively been downloaded about 150 times to date. “It’s just great to share the students’ amazing work beyond the classroom!” she says.

In celebration of her ongoing dedication to openness, Stefanie is this year’s proud recipient of the University of Ottawa Library Open Scholarship Award. Established in 2016, the award “recognizes faculty members and instructional staff who are committed to exploring the opportunities afforded by the global shift toward an open ecosystem of scholarly research and teaching.”

In this short video, Stefanie sits down with Jeanette Hatherill, uOttawa Scholarly Communication Librarian, to discuss open access, research, education, and more.

Find out more about the Open Scholarship Award on the uOttawa website, or check out the ScholCommLab’s research into open access, open education, and open data.

Preprint comments: A place for praise, critique, and everything in between

Once all but unknown to anyone but economics or high energy physics researchers, preprints are becoming more popular across the disciplinary spectrum. These unreviewed reports allow scholars to share their work with the wider research community as soon as it is finished, without having to navigate what can sometimes become a lengthy peer review process. This ability to receive almost-instant feedback may be the preprint’s greatest strength — or, at least, it could be, if we knew that this feedback process were truly taking place. Until recently, no one had ever systematically analyzed whether preprint server comment sections contain useful commentary of any kind.

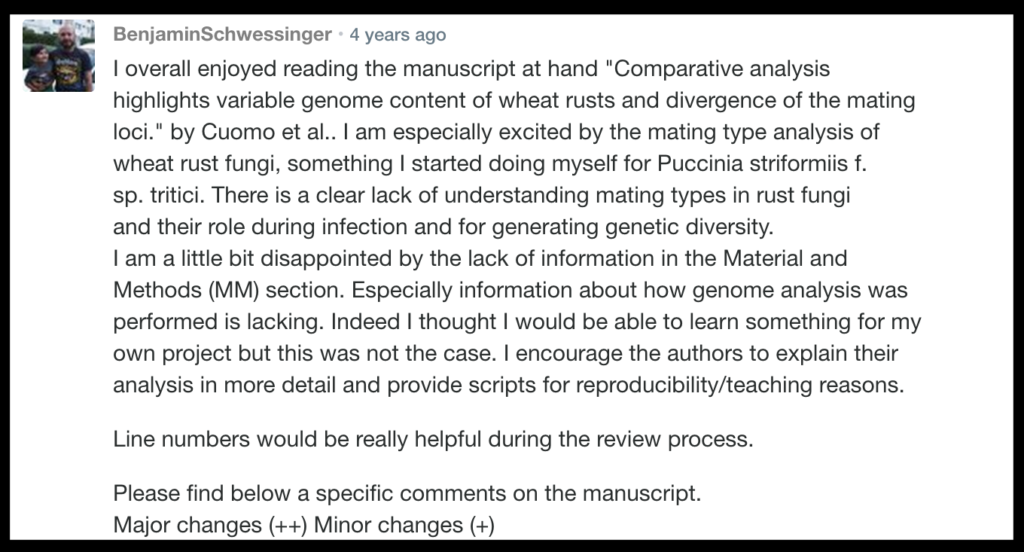

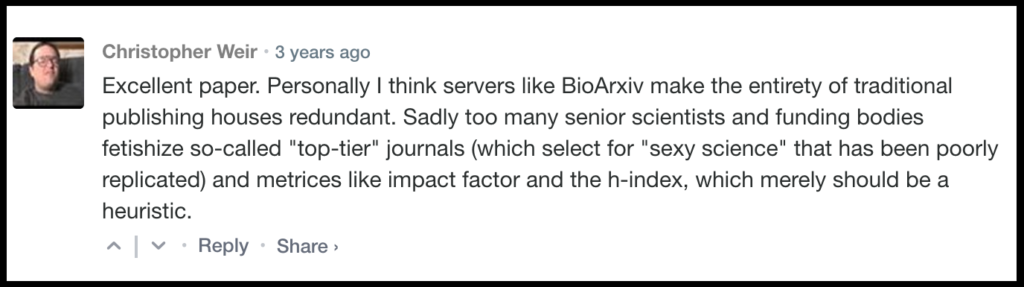

That’s where new research by Mario Malički, Joseph Costello, Juan Pablo Alperin, and Lauren Maggio comes in. The study, which is (appropriately) available in preprint, collected all comments posted to bioRxiv preprints between May 2015 and September 2019. The team filtered this data set to include only the comments that had not received any replies, then carefully read and classified them. For each of the almost 2000 comments, they assessed whether the commenter was an author of the preprint or someone else. They also analyzed the text itself, categorizing it as a praise, critique, question, or something else entirely.

In this interview, Mario shares key insights from the study, touching on peer review reports, compliment sandwiches, and everything in between.

Why was it important to look at preprint comments?

I think the biggest criticism about preprints has been the fact that they are not peer reviewed. Comments could potentially be a way to deal with that criticism, as they enable other scholars to look at what other researchers have said about it.

When you were analyzing these comments, did you find any evidence of that actually happening — of people reviewing preprints?

For me, there were two big surprises in this study. The first was that a lot of the comments (31%) were actually made by the authors themselves. I would have thought that all of the author comments would be replies to other comments on certain aspects of the preprint.

The second surprise was that 12% of comments were full peer review reports. I thought that the majority of people would write maybe one or two comments or just a simple question, but there were full peer review reports in our sample, which was very nice to see. I think that shows how people approach things. As a commenter, you have a choice: Will you ask all the questions at once — everything that bugs you — or are you just going to ask the one thing that intrigues you? We found evidence of both of those practices.

When you say commenters were posting full peer review reports, what did that actually look like?

To me, they look exactly like the ones that I get when I invite experts to review papers for my journal. They usually start with “Dear authors, thank you for the opportunity to look at your paper. I found it interesting but there are some things that I would like to address.” Then they typically create a list of bullet points to raise more issues, and add something like, “Hopefully this will help you make your paper better.”

Basically, it’s a compliment sandwich.

He he, yes. We actually found the compliment sandwich in a lot of all our comments. Sometimes in the full peer review reports, and sometimes they were just included in a question or two. Around 50% of those less formal comments had little positive comments mixed in between criticisms or questions. Maybe it's just the way that we communicate: first a little praise, and then attack.

“We actually found the compliment sandwich in a lot of our comments… Maybe it's just the way that we communicate: first a little praise, and then attack.”

Mario Malički

Tell me more about those more casual one-off comments—the other 88% of your sample. What did those look like?

We found all sorts of things. There would sometimes just be a simple “thank you.” But there were also questions from patients about diseases that they had that the paper was dealing with, or mentions along the lines of, “We did a similar study, you might be interested in it.” Then there were questions like, “I see maybe a problem in your figure. Am I interpreting this right?” Or, “Do you know if anyone else is working on this?” Or, “What happens next?”

When we classified them, the majority of these non-author comments were either suggestions or criticisms. We did not, however, count how many different critiques or how many different questions they raised. Still, it was interesting to see that, even in these comments that were not full peer review reports, there were lots of readers providing feedback or critique on a specific aspect of the preprint.

What’s the main takeaway of this research for the scholarly community?

It’s a tricky one to answer, because we looked at just those preprints that had received only a single comment. Sixty percent of those we analyzed were comments not by the authors but by someone out there commenting on the paper. None of them got a reply, but none, to us, looked like comments that couldn't be replied to.

Now, we know that bioRxiv doesn't prompt authors when a comment has been made to their preprint, so it is possible that authors were maybe not aware of the comments that were raised. But I think it may be a similar situation as the one we find with platforms like PubPeer, where anyone can comment on papers after they’ve been published in a journal. We know from these platforms that often authors will not reply. Of course, there is no international law or regulation that forces you to reply to a critique or even a question that someone raises out there in the world. You have no obligations, except maybe your own personal interest. But I'm always thinking that, if it was me, I would want to try to answer.

Do you think we can improve comment sections? It sounds like there's potential for some really meaningful conversations to take place there.

Yes, I really think there is. Maybe the corresponding author should get at least an option to receive some sort of notification when a comment is made to their preprint. Because I feel that, unless this is done, people may stop using this public platform to reach authors; they will just write a personal email instead. While a personal email may be beneficial to you—the person who asked the questions—it’s only when the public can see your questions that others can benefit from them, too.

While a personal email may be beneficial to you—the person who asked the questions—it’s only when the public can see your questions that others can benefit from them, too.

Mario Malički

In another (upcoming) study, we actually found that 70% of all preprint servers have comment sections. But none of these servers have yet come out with studies on the frequency of use, the outcomes, or what the users want. So I think that we need a little bit more research. We need to see, in the long term, how sustainable preprint server comment sections are and how their role in scholarly publishing might evolve. There is more research coming out on the effects of open peer review in scholarly journals, and more and more journals embracing open review practices. As comments, in a way, resemble open scholarly communication, I expect we will see both more research and more use of public commenting in the near future.

For more information, check out the Preprints Uptake and Use Project Page or read the full preprint at bioRxiv.

New study: Tracking opioid science in the news

As governments across the world grapple with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, several other urgent crises have taken a back seat.

Among them is the opioid epidemic. Here in Vancouver, BC, where almost half of our team is based, the effects of this second, fatal crisis are visible every day. Just this May, our province reported a record-breaking number of overdose-related deaths: 170 in a single month, or about 5.5 a day. But the consequences of opioid addiction extend far beyond our city’s limits. In the US, annual death counts have also reached record highs — and appear to be rising with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In light of this pressing issue, we decided to research the crisis from a communications perspective, analyzing more than 150 news stories to understand how online journalists report on scientific studies about opioid-related disorders. The results of analysis (published this week in Frontiers in Communication) suggest that, while the epidemic itself may remain controversial, news coverage of opioid-related science has not followed suit.

Opioid studies rarely receive online news coverage

“Solving the opioid crisis will involve confronting several big issues, including the causes underlying substance misuse and addiction as well as the social stigma surrounding addiction and mental illness,” says Lisa Matthias, a visiting scholar at the ScholCommLab and lead author of the study. “But I think at the bottom of these issues are larger questions of deservingness and credibility. Who deserves help? And what information do we trust when deciding how to provide that help?”

Our study focuses on that second question, recognizing the critical role the news media can play in shaping how we approach health and social problems and possible solutions. Using data from Altmetric — a data science company that tracks online mentions of scholarly publications — our team analyzed how often opioid-related research was mentioned by top Canadian and US online news outlets between 2017 and 2018. While the crisis itself received extensive news coverage at the time — more than 8,500 stories across the nine outlets we analyzed — less than 2% of those stories mentioned any relevant research.

These results are surprising, especially given continued calls for evidence-based responses to the crisis. “I would have expected journalists covering the crisis to bring in more opioid science,” Lisa remarks. “In my opinion, scientific research can help guide the way forward.”

Few news stories provide context about the opioid research they cover

Our team performed a detailed analysis of the news stories that did mention opioid research to understand how that science had been communicated to audiences. We found that most stories portrayed the opioid research they covered as being valid and credible — trustworthy information that audiences could rely on.

In some ways, this finding offers hope, especially given that news coverage of other controversial topics, like climate change or vaccination safety, have historically framed scientific findings as more controversial or uncertain than they really are. But there are also drawbacks to portraying research findings as established facts, especially when the science behind them is still preliminary or emerging.

“Importantly, we found that this framing of science as trustworthy was usually done by omitting details about the study rather than emphasizing the credibility or validity of the research,” Lisa explains. “Science was usually mentioned in passing, in the context of some larger issue. So there was rarely much discussion about the methods or limitations behind the results.”

Covering science in a changing media landscape

Of course, there may be practical reasons for this lack of context in science coverage. Attention spans are limited online, and journalists sometimes have to cut details to keep readers engaged. Our media landscape is also changing as reading habits and funding models evolve. As publishers struggle to keep up with the 24-7 news cycle amid shrinking revenue streams, not every journalist will have the space, time, or resources to provide lengthy discussion of scientific methods in their stories. But by leaving out key information about the research design, these stories offer few opportunities for audiences to critically engage with the research presented to them.

"for citizens and policy makers to be able to make well-informed decisions, we have to find ways to communicate study results effectively"

Identifying how these journalistic choices might affect readers and policy makers is a task for another research study, but our findings raise important considerations about the nature of opioid news coverage — and of science news more generally: “Scientific research is one critical puzzle piece in solving many of the issues we face today,” says Lisa. “But for citizens and policy makers to be able to make well-informed decisions, we have to find ways to communicate study results effectively, without misrepresenting the science behind them.”

"Framing science: How opioid research is presented in online news media" is a collaboration between Lisa Matthias, Alice Fleerackers, and Juan Pablo Alperin. Read the full study at Frontiers in Communication.

How to use social annotation in the classroom

Want to make online readings a little more engaging? Social annotation (SA) may offer one solution.

SA tools allow students to highlight and comment on online course materials, sharing questions and ideas with each other as they read. When used effectively, they can help boost student motivation, reading comprehension, and more. And students seem to like them: our lab's research suggests they see these tools as useful for learning and for building community in the classroom.

If you're curious to try social annotation but unsure how to start, check out these two introductory videos. The first is a basic introduction to social annotation: what it is, how it works, and how to use it to enhance learning. The second offers simple instructions for how to use Hypothesis—a popular SA tool—for online reading.

Introducing Social Online Annotation

A basic overview of what social annotation is and how it works. To skip ahead to what you should do with SA, jump ahead to min 10:45.

How to use Hypothes.is for Social Online Annotations

An overview of how to use one popular SA tool: Hypothesis. Watch the whole video or skip ahead to a specific section:

- Creating an account - 0:40

- Add Hypothes.is to your browser - 1:20

- Add Hypothes.is to Google Chrome - 2:17

- Joining a Group - 3:35

- Making an annotation - 4:00

- Formatting annotations - 5:24

- Adding a hyperlink - 6:30

- Adding an image - 8:08

- Adding a video - 9:28

- Replying to an annotation - 9:57

- Annotating PDFs - 11:07

- Annotating PDFs that are on your computer - 12:30

Find out more about social annotation on our blog or check out the research study here.

Communicating science: New book explores science communication across the globe

How did modern science communication begin? How has it evolved from one country to the next? What social, political, and economic forces inspired those changes?

Published this week by ANU Press, Communicating Science: A Global Perspective explores all of these questions and more. The impressive volume is a collaboration between seven editors and more than 100 authors, including the ScholCommLab’s own Michelle Riedlinger (Queensland University of Technology) and Germana Barata (Universidade Estadual de Campinas). Featuring stories from 39 countries, it charts the development of modern science communication across the world, from Uganda to Singapore, Pakistan to Estonia.

In celebration of the book’s launch, the ScholCommLab spoke with Michelle and Germana about what Communicating Science can tell us about the past, present, and future of science communication.

You’re both co-authors (with Alexandre Schiele) of the Canadian chapter. Tell me about the mapping research you did at the ScholCommLab and how it relates to the book.

Michelle Riedlinger: I was a member of the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada and I was helping to organize some local SWCC events in British Columbia. One of the other event organizers was a member of the SWCC Board and she talked about the recent name change of the organization from the Canadian Science Writers Association to the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada. She said that the organization was seeing changes in membership, and also seeing that science communication was exploding online. We got together with the SWCC President at the time, Tim Lougheed, and decided, with Germana—who was already focused on mapping work and was a visiting scholar in the ScholCommLab at the time—that it might be a good idea to map online science communication in Canada.

Where do we see science communication online? Who's doing it, how are they doing it, and what are their values? These initial questions sparked what would become a three-year-long project exploring online science communicators in Canada—and eventually this helped us write the Canadian chapter. We’d already been looking at science communication in Canada, so it was a nice easy step to then think: Alright, this is where we are. Now, where did we come from?

Germana Barata: The project was a great opportunity to use altmetrics—social media metrics or the social attention to scientific content on online platforms—as a tool to track self-identified science communicators on Twitter. We located science papers shared by Twitter users geolocated in Canada who used keywords related to science communication on their mini-bios, in either English or French. It is interesting that a mere translation of keywords wasn’t enough to find science communicators in French and English, so we had to define specific keywords for each group and the keywords related to different concepts of science communication. Although limited, the method appeared to work well to locate active science communicators on social media.

What did the project teach you about Canada’s science communication landscape?

GB: The mapping project showed us that there is an enriching community of science communicators using social media to communicate science to society—most of whom are self-taught and do not earn a living with science communication but believe that is it important to reach broader audiences. The majority were engaged women, which was a positive result. I was also impressed with the quality and variety of strategies that everyone is practising, with a strong presence of environmental and health issues, as well as science and art approaches.

"social media is a place where originality, culture, and regionality stands out and where everyone may find a niche for their communication efforts."

Germana Barata

My home, Brazil, is a huge country with intense, creative activities in science communication. My work in Canada made me realize that social media is a place where originality, culture, and regionality stands out and where everyone may find a niche for their communication efforts. It made me look to my country with more optimism.

Tell me more about the Canadian chapter. What makes our science communication story unique?

MR: Canada's really interesting to write about. It’s an unusual country in terms of being bilingual, with the US as its closest neighbor and also having colonial influences. A lot of Canadian science communication activities and processes have been influenced by what is happening in the US, but with a distinct Canadian flavor. For example, the SWCC came out of a branch of the US: The National Association of Science Writers (NASW). That US group started in 1934 and is still going strong today. Canadians could be members of the NASW, but in the late 60s they decided that they wanted to have their own association. In fact, it is SWCC’s 50th anniversary this year. Like NASW, SWCC maintains a focus on advocating for quality science writing but they also recognize that a huge range of professionals communicate about science and also need a professional networking organization. In other countries, professional science communication groups have always included press officers and science outreach professionals—they didn’t start exclusively as science journalism associations.

You mentioned Canada’s bilingualism. How has that influenced its science communication story?

MR: Quebec has a substantial section of its own in our chapter because they have their own science communication story to tell. We didn't see a lot of overlap of cultural institutions. We see Canada’s two cultures distinctly in the history of its science communication. English-speaking Canada definitely has colonial UK influences: ideas around science participation and dialogic communication. But in French Canada, to be a cultural citizen means being cultured in science—so a lot of Canada science communication “firsts” happened in Quebec. The first radio program focused on science, the first Masters and PhD graduates in science communication, and the first national conference on science communication all happened there. Canada’s National Science Week also started in Quebec. So, over the years, we see this strong connection between science and culture, or science and society, heavily supported by the Quebec government. I think that is a really interesting difference.

How has Canada’s science communication landscape evolved over time?

GB: Science communication used to be dominated by men—by scientists, at first, but increasingly by science journalists. Fortunately, the internet and social media have opened windows of opportunity to a more varied, multidisciplinary, and multimedia community that has dropped the need for mediators to bridge science and society. Fighting denialism and fake news have shown us that we need a growing active community of science communicators and that to empower them we should be able to provide them with more training, funds, and visibility. They are doing an amazing job.

"Fighting denialism and fake news have shown us that we need a growing active community of science communicators and that to empower them we should be able to provide them with more training, funds, and visibility."

Germana Barata

Michelle, you were also an editor for the book itself. Did that process reveal a lot of similarities in terms of how science communication stories developed in different countries?

MR: As an editor, I was excited to read about science communication happening in the other countries and how diverse it was—but also to get a sense of where there was cohesiveness. One common thread was government support and funding. This has always been a driver of science communication. For example, after World War II we saw a big push for science by governments in many countries. And science communication has followed this government or national investment in science and technology in many instances.

I was also interested in the political, cultural, economic forces in different countries and what those forces meant in terms of driving science communication. In places like the Netherlands, for example, the idea of a collective social system really shaped how science communication developed. Ideas around participatory science communication have been imported from the Netherlands to the UK and then carried on into many other countries.

It’s a strange time for science, and for science communication. Does the book offer a sense of where science communication might be headed next?

MR: I hear people in the science communication community talk about how science communication has “failed” us or that science communication is in “crisis.” But what's really lovely about reading this book is seeing that science communication is always innovating. There have been crises throughout our modern history, but science communication is always changing, bringing in new people and skills, and responding to the social, political, and economic circumstances that we're in. There’s no endpoint.

Another thing that this project confirmed for me was the importance of online science communication for the field. A lot of people are doing online work with very few resources, and I think one of the things that governments, professional associations, and research organizations can do is to better support them. If we're keen to celebrate good science communication in the field, then we need to look at what people in the community value—and it’s happening online.

"There have been crises throughout our modern history, but science communication is always changing, bringing in new people and skills, and responding to the social, political, and economic circumstances that we're in. There’s no endpoint."

Michelle Riedlinger

What are some takeaways you hope the book leaves readers with?

GB: I'm happy that this important book is open access, so that it may impact the science communication community worldwide. With access to all chapters, we can be inspired by different practices but also value the particularities of every nation. Science communication efforts can involve different motivations, publics, and actions according to the scenario, culture, and policy it is exposed to. It is an important publication for students and practitioners of science communication—a resource to help communicators identify with our huge, international community as well as better understand the influences of our practice.

MR: I don’t think this is the kind of book that readers will read from cover to cover. I think they will dip in and out of it. But I’d like to think that readers will leave this book thinking about what they might do within their own sphere of influence to support innovative science communication. I’m thinking about governance, government and commercial support, and community action. I think this book also highlights science communication’s roles in benefiting communities, because science communication isn't an end in itself. It does work for our communities and societies. For me, the stories of collective action in this book are something to celebrate. I'd say they might inspire a way forward.

Another thing I love in this book is the focus on the interaction between scientific knowledge and Indigenous knowledge in many nations. The New Zealand chapter is a wonderful example, with stories about Maori science and what researchers are learning through it. But there are big challenges too. For example, the South African chapter describes the challenges associated with creating a scientifically literate society while juggling government priorities, Indigenous knowledge systems, and modern science. I think a focus on diversity, of values and peoples, will only increase for science communication. This is one of the things that came out of the mapping work: many young science communicators working online are advocating for a more diverse science and technology community, and this includes a more diverse science communication field. I think that's a wonderful direction for our community.

Communicating Science: A Global Perspective (2020) is available for purchase or free download from ANU Press. Celebrate its digital launch on September 15 (1-2 PM London UK time).

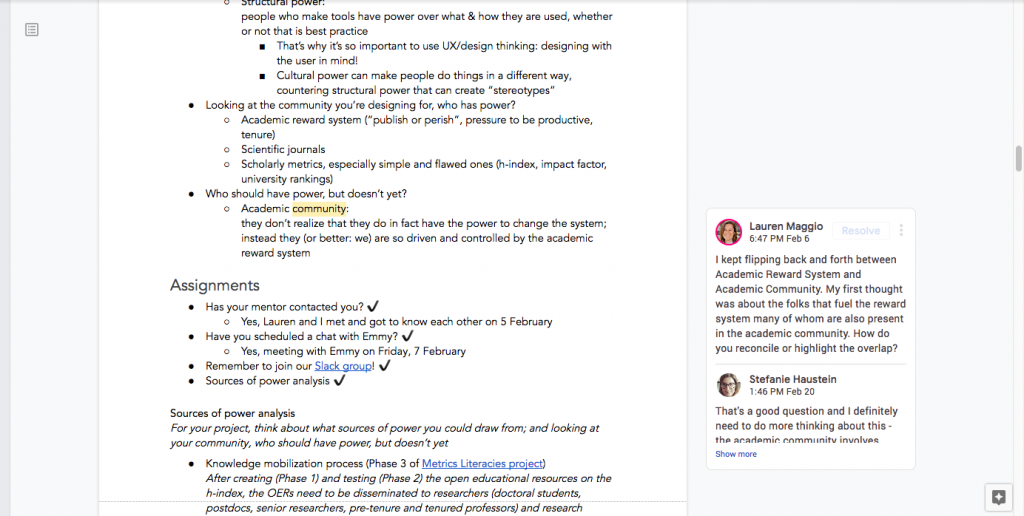

ScholCommLab Co-director Goes Back to School: Open Innovation Leaders 2020

Stefanie Haustein was scrolling through her feed when she stumbled on it. A tweet from eLife Innovation promoting a program called “Open Innovation Leaders.” It promised design thinking, open communications, and sustainability—all with only a two hour per week time commitment. Intrigued, she clicked through.

Three months later, Stefanie is five weeks deep into what is fast becoming a favourite part of her work week. Designed to support “innovators developing prototypes or community projects to improve open science and research communication,” the eLife Innovation Program offers a mix of expert advice, presentations by guest speakers, collaborative workshopping, homework assignments, mentorship, and more.

“The idea stemmed from running the eLife Innovation Sprint, a collaborative hackathon where we bring together technologists and researchers to develop open prototypes for open science,” explains Emmy Tsang, eLife’s Innovation Community Manager and organizer of the Innovation Leaders program. “We saw so many creative ideas for tools to change the ways we do and share research, but most were not continued beyond the event.”

To help those creative ideas flourish, eLife started Innovation Leaders. “We want participants to feel empowered and prepared to lead their own open projects for open research,” says Emmy. “We thought about what achieving that would require—skills and training…, connections to people [who] can help..., funding opportunities—and we hope to provide all of those with the programme!”

Each week, the group meets via Zoom to discuss their projects and receive training in everything from problem definition to vision statement development. They also meet one-on-one with their mentors—researchers, programmers, and others who have volunteered to share their expertise with the innovators-in-training. All of the materials, notes, and even recordings of the calls are openly available so that others can learn from them too.

“Emmy is doing such a fantastic job of preparing everything,” says Stefanie. “We have guest speakers every week. There’s lots of content and all of the materials are open for anyone to reuse.” The assignments are very helpful, even if they are quite a bit of work. “I really like the whole setup of having weekly calls and doing a little homework to push yourself to move forward,” she says. “It almost feels like I’m back in school!”

But the best part of the program, Stefanie says, is the mentorship aspect. By a stroke of coincidence, she was paired with Lauren Maggio, an Associate Professor of Medicine at Uniformed Services University and a ScholCommLab collaborator.

“I meet with her every two weeks for half an hour to an hour, and I ping her in my notes document if I have a specific question and need feedback,” says Stefanie. “It’s really helpful.”

Stefanie sees Open Innovation Leaders as the perfect opportunity to make progress on the ScholCommLab’s Metrics Literacies project. The project team is working on developing open educational resources aimed at improving the understanding and appropriate use of scholarly metrics in academia.

“We’ll use different types of audiovisual media, like stop motion animation, podcasts, or even video games,” explains Stefanie. “Researchers who are already overwhelmed with keeping up with their own fields shouldn’t have to add to their long reading list. Instead, they could watch a fun five-minute video and know everything about the h-index.”

The research will involve aspects that are unfamiliar to Stefanie, so she’s grateful for the support. “I'm still an early career researcher, and Lauren is applying for full professorship now,” she says. “It’s really nice to have a senior scholar look over my shoulder and give me some advice.”

While there’s still a long way to go in the program, Stefanie is excited by what she’s learned so far. “All of the exercises that we're doing during the calls and assignments help to shape the project in different ways,” she says. “For example, our team hadn't thought about having a vision statement, because that's not something that’s usually put into a research project, per se. But I think it's really helpful.”

Her latest assignment was to develop a roadmap, a path to understanding the problem and how she can solve it. “Looking at the project again and again, from different perspectives with different questions, is really making it better,” she says. “It feels more solid.”

As she moves into her sixth week in Open Innovation Leaders, Stefanie is already thinking about how she could use the strategies she’s developed in future projects. “I think the program offers a nice scaffolding to approach something new,” she says. “It’s a great way to move beyond the research and think about the bigger picture.”

To find out more about Open Innovation Leaders 2020, check out the program webpage or follow along at Stefanie’s open notebook.

Celebrating one year of Open Science Beers

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

"It all started with a pang of jealousy," says Asura Enkhbayar when asked what inspired him to start Open Science Beers YVR. Stefanie Haustein had pointed out that Montreal hosted a regular open science meetup every Wednesday. But Vancouver, Asura realized, had nothing of the sort.

"I had always found it quite amazing that Vancouver was the home of so many amazing folks involved in Open Science, Open Access, Open Data without offering the opportunity to bring all of them together on a regular basis," he says. "I guess that is why we started Open Science Beers YVR, and why we're now in our second season."

Throughout 2019, the monthly events brought together scholars, students, industry professionals, advocates, and others interested in all forms of open scholarship. Conversations meandered from serious to lighthearted, covering everything from open data protocols to bowling.

"I think that it's really giving faces to open science," says Asura. "We talk open science, OA, Elsevier, and corporate greed all the time anyways. But it's super nice that all the people involved sometimes just might want to get together and chat about life and a have a drink."

As we gear up for our second season, we're sharing some reflections (and, of course, some corny selfies!) from the year gone by.

Here's what past attendees have to say about Open Science Beers:

"I like attending OSB because I like hanging out with conscientious and quirky people who are anti-establishment and mutually interested in the destruction of paywalls," says Michelle La, a master's candidate in Anthropology at Simon Fraser University.

Carina Albrecht, also a master's student at SFU, agrees. "Open Science Beers is a great way to have fun conversations with the most interesting people and connect to students or scholars from around the area and many places of the world," she says. "Almost every time I go to one event I have the opportunity to meet someone new."

"In the spirit of the open movement, open science beers provides an inclusive, accessible opportunity to discuss ideas across scientific disciplines in a way that academia always strives to but never quite achieves," adds Erfan Rezaie, a physics instructor at Langara College and Capilano University.

Thanks for an amazing year of Open Science Beers. We're looking forward to seeing you again in 2020!

Join us at the next Open Science Beers YVR at the Alibi Room on Thursday, January 30 at 6 pm. Or, sign up for our mailing list for a monthly invitation.

FORCE2019: Establishing a shared vision for preprints

This blog is cross-posted from ASAPbio and reused under CC-BY 4.0 license. Please add any comments and annotations on the original post on the ASAPbio blog.

Following a panel discussion about “Who will influence the success of preprints in biology and to what end?” at FORCE2019 (summarized here), we continued the discussion over dinner with the panelists and other community stakeholders:

On table 1:

- Emmy Tsang (facilitator), eLife

- Theo Bloom, BMJ and medRxiv

- Andrea Chiarelli, Research Consulting

- Scott Edmunds, GigaScience

- Amye Kenall, Springer Nature

- Fiona Murphy, independent consultant

- Michael Parkin, EMBL-EBI (EuropePMC)

- Alex Wade, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

On table 2:

- Naomi Penfold (facilitator), ASAPbio

- Juan Pablo Alperin, ScholCommLab/Public Knowledge Project

- Humberto Debat, National Institute of Agricultural Technology (Argentina)

- Jo Havemann, AfricArXiv

- Maria Levchenko, Europe PMC, EMBL-EBI

- Lucia Loffreda, Research Consulting

- Claire Rawlinson, BMJ and medRxiv

- Dario Taraborelli, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

To tackle some tricky issues as a group with diverse perspectives, we discussed five straw-man statements about how preprints may or may not function. Emmy’s table discussed:

- The level of editorial checks and/or peer review that a preprint has been through should be transparently communicated at the point of access to the preprint

- It should always be free for an author to post a preprint

- Preprints should not be used to establish priority of discovery

- Preprint servers should be agnostic to upstream and downstream tools and processes

Meanwhile Naomi’s table (pictured below) discussed “preprint servers should not be supported by research funders and policymakers unless they demonstrate community governance”, before exchanging different visions for what preprints could be.

Straw-man statement 1: The level of editorial checks and/or peer review that a preprint has been through should be transparently communicated at the point of access to the preprint.

While we generally agreed that editorial checks and any reviewing done on a preprint should be transparently communicated, we quickly realised we have different visions for what transparency means in this context. It is important that we take readers’ needs and experiences into consideration: a researcher who is casually browsing may just need to know the level of scrutiny a preprint has been through (none? Pre-screening for compliance with ethical and legal requirements and of scientific relevance? Some level of deeper peer review?), while a researcher who is digging deep into that research topic or method may find peer-review comments and version histories useful. Some information, such as retractions, should be communicated clearly to all readers. For effective curation, it will also be crucial that information on the checks and reviews be adequately captured using a well-defined and agreed-upon metadata schema. But how can such data be practically captured across a distributed set of servers? Peer-review and editorial processes nowadays vary hugely between journals and preprint servers, so to what extent can we effectively schematize these processes?

Straw-man statement 2: It should always be free for an author to post a preprint.

We unanimously agreed that preprints should be free at the point of use.

Straw-man statement 3: Preprints should not be used to establish priority of discovery.

Ideally, the priority of discovery should not matter, but we recognised that, in the current research climate, this issue should be addressed. Once a preprint is published in the public domain, scientific priority of the work described in the preprint is established. We recognize that current legal instruments may not act in line with this: for example, US patent law still establishes priority based on the filing of the patent application, and any public disclosure – by preprint or informal meeting – can undermine this. Further consideration and clarity is needed for how posting a preprint intersects with priority claims and what this means for discovery and intellectual property.

Straw-man statement 4: Preprint servers should be agnostic to upstream and downstream tools and processes.

To use preprints to their full potential, we think preprint servers should be compatible and interoperable with upstream and downstream tools, software and partners, and at the same time not indifferent to information or pointers towards emerging practices, community standards and so on. For example, upstream processes to capture and curate metadata can be invaluable for discovery. Community preprint servers can also advise on best practices for downstream workflows, adding value to the work and facilitating reuse and further contributions.

Straw-man statement 5: Preprint servers should not be supported by research funders and policymakers unless they demonstrate community governance.

What do we mean by community governance and why is this important?

We discussed that a major motivation behind the push for community-led infrastructure is to minimize the chance of commercial interests being prioritized over benefit to science, as has happened with the loss of ownership and access to peer-reviewed manuscripts (by the collective) due to the profit imperative of commercial publishers. Here, we may be asking: are commercial interests prioritized over the purpose of sharing knowledge and facilitating discourse, and how might we ensure this isn’t the case for preprint servers?

Beyond commercial drivers, we acknowledged that service/infrastructure providers (publishers, technologists) are making process and design choices that affect user behaviour. This was not raised as a criticism – instead, several of us agreed that the behaviour of individual researchers is often largely guided by their immediate individual needs and not collective gain, due in part to the pressure and constraints of the environment they are working within. People who work at publishing organizations bring professional skills and knowledge to the reporting of science that are complementary to academic editors, reviewers and authors. The question is how to ensure process and design choices are in line with what will most readily advance scholarship.

We discussed how no single stakeholder can represent the best interests of science, nor is there a single vision on how to best achieve it. Is advancing the growth of a particular server a boon for the whole community? Or should all decisions be made in the interests of the collective? Whose content should we pay attention to, and how do we know who to trust? How is any one group’s decision-making process accountable to the whole? We asked these questions with a shared understanding that many journals operate as a collaboration between members of the academic community and publishing staff, and that some preprint servers (such as bioRxiv) are operated along the same lines. However, whether and how this works may not be transparent, and the lack of transparency may be the central issue when it comes to trusting that decisions are in the collective best interests. Leaving the decision of who to trust to funders or policymakers may not reflect what the broader community wants, either.

So, how might decisions at a preprint server be made in a way that the broader community can trust? We looked to other examples of community-led governance – whether that’s the community having input into decisions or being able to hold decision-makers accountable for them, particularly to moderate any decisions influenced by commercial interests. One mechanism is to run an open request for comments (RFC; for example, see Wikimedia) so that anyone can provide inputs. However, there needs to be a transparent and fair process to decide whose input is acted upon, and a recognition that such processes do not guarantee better outcomes. Alternatively, projects could employ a combination of mechanisms to listen to different stakeholders: for example, the team behind Europe PMC listen to users through product research, to academics through a scientific advisory board, and to policymakers through a coalition of funders. This latter process can provide a resilient decision-making process, not easily directed by a single stakeholder (such as anyone representing the commercial bottom line), but it can be costly in terms of management resources.

User behaviour is influenced by social and technological decisions made at the infrastructure level, so how a preprint server is run, and by whom, will contribute to whose vision for preprints in biology will ultimately play out in reality. The discussion continued online after our dinner.

Can we establish a shared vision for preprints in biology?

Our experiences, spheres of knowledge and values all influence what we each envision preprints to be and become: from helping results to be shared in a timely manner, to disrupting the current commercial publishing enterprise.

Emmy’s table discussed how confusion around what constitutes a preprint (and what does not) creates difficulties when developing tools, policies and infrastructure for them. With different use cases for preprints, and where communities may want to share different pre-publication research outputs, it was proposed that narrowing the definition of preprints to "manuscripts ready for journal publication" could help simplify technological development, communication and advocacy work. Preprint servers would then have the sole purpose of housing and serving preprints. This may not capture all use cases of preprints, but it was seen as a worthwhile trade-off for increasing adoption at this moment in time. However, on Naomi’s table, we proposed it may be useful to be transparent about more complicated and/or extended visions for change, to avoid progress stalling once adoption of this simplified definition is stable.

Importantly, we discussed our concerns about preprints, sometimes envisioning situations we did not want to see materialize:

- Preprints may not always be free to post and read, depending on the financial models used to sustain the costs of preprint infrastructure – there was a word of caution about how the open-access movement in the US and Europe is currently pursuing the use of article processing charges (APCs) to pay for open access. This may be how preprints are paid for unless other options, such as direct support by funders and institutions (for example, through libraries), are used.

- With preprints available publicly, what if they are misunderstood or misinterpreted? What if incorrect science is spread like “fake news”? We discussed how some patient groups are able to critique the literature without formal science education and that peer review does not guarantee correctness. Offering readers greater transparency and information about whether and how the work has been reviewed by other experts would be helpful.

- Preprints may not disrupt scholarship – we may continue to operate in a world where rapid, open, equitable access to the production and consumption of knowledge is not optimized for. This may be seen today by the use of preprinting to claim priority of discovery without including access to the underlying datasets, and by the uptake of journal-integrated pre-publication where authors can show they have passed the triage stage at journal brands with prestigious reputations.

- Publisher platforms may generate lock-in, as authors post the preprint to their platform and are then directed to remain within that publisher’s peer-review channels.

- We briefly talked about the use of open resources to generate profit: do preprints need protecting from commercial exploitation through the use of licensing clauses, such as share alike (-SA)? Maybe not: profit generation on open resources may not be a problem, as long as the community agrees that the benefits of openness continue to outweigh any exploitation, as is currently seen to be the case for Wikipedia.

So what did we want to see happen? We concluded by sharing our own visions for preprints, including:

- The main venue for research dissemination, in a timely manner, which is free to authors and readers, and upon which peer review proceeds. This peer-review may be community-organized; it may be more efficient and timely when this is needed, for example during infectious disease outbreaks. The verification and validation of a preprint may change over time, and versioning enables the full history to be interrogable.

- A transparent record of scientific discourse that is a resource for learning accepted and/or preferred practices, within a discipline (for example, the appropriate statistical method to apply in a given experimental setup) or more broadly (for example, how to be a constructive peer reviewer and responsible author).

- Supporting faster and better advances in medicine, particularly in a world where patients have improved their own lives by hacking medical technologies (e.g. #WeAreNotWaiting) or showing their clinician(s) evidence from the literature.

- A vehicle through which researchers can connect and engage with other audiences (patients, policymakers), and learn how to do this well.

- A way for knowledge generation and use to be more equitable and inclusive, for example by increasing the visibility of researchers around the globe (as AfricArXiv and others are doing for researchers in or from Africa).

- A vehicle for scholarly discourse that does not necessitate in-person attendance at conferences, reducing the use of airplane travel and avoiding exclusion due to costs, visa issues and other exclusionary factors.

Moving forward, suggestions were to include different voices in the discussion, provide more thought leadership, develop a consensus vision for the future of preprints, develop best practice guidelines for preprint servers, and provide users with sufficient information and clarity to help them choose (through action) the future they wish to see.

What is the future you wish to see? We invite you to talk about this with your colleagues and leave a comment on the original version of this post.