Studying “Pre-Truth” Science: The 2023 Scholarly Communications Institute

By Alice Fleerackers, with input from Yao-Hua Law, Mario Malički, Luisa Massarani, Chelsea Ratcliff, and François van Schalkwyk

The annual Scholarly Communications Institute (SCI) offers opportunities for interdisciplinary and international teams to come together to pursue complex projects related to a common theme. In this blog post, lab member Alice Fleerackers reflects on her experiences collaborating with scholars and journalists to understand and improve the ways preprints are reported in the news.

Over the last four and a half years, I have become deeply obsessed with something I never would have expected: preprints.

If this term is unfamiliar to you, don’t worry: You’re not alone. When I started my PhD back in 2019, I, too, had no idea what a ‘preprint’ was. I started to understand while editing a series of (very technical) blog posts written by Mario Malički, Maria Janina Sarol, and Juan Pablo Alperin. But this was just the beginning of what would turn into a strange romance with preprints.

Through multiple rounds of frantic googling, I learned that preprints are papers that researchers make publicly available so that others can see and comment on their work. They differ from traditional academic articles, which are first submitted to a journal and are only published if they pass peer review. As a free way to make research publicly available, they are a core part of open science. They also let researchers get their results out into the world immediately—without having to wait months (or years) for their work to go through peer review and journal editing.

![An inlet popping out of the computer screen, reading "This article is a preprint and has not been certified by peer review [what does this mean]?"](https://www.scholcommlab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Preprint-disclaimer-2-1024x538.png)

My true obsession began a few months later, when COVID-19 preprints started to make headlines. From research on how the virus spread to whether the controversial hydroxychloroquine drug was effective, un-peer-reviewed studies became a mainstay of pandemic media coverage.

These news stories fascinated and perplexed me. They raised so many questions that I couldn’t find answers to: Why do journalists use preprints? How do they vet these studies without the ‘safeguards’ of peer review? How do they make it clear to audiences that these papers are still unreviewed? Have preprints always been a part of journalism, or was the pandemic an exception? These questions became the basis of my dissertation—which I will defend just a few weeks from now.

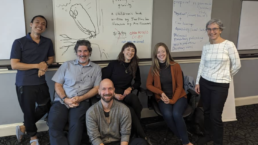

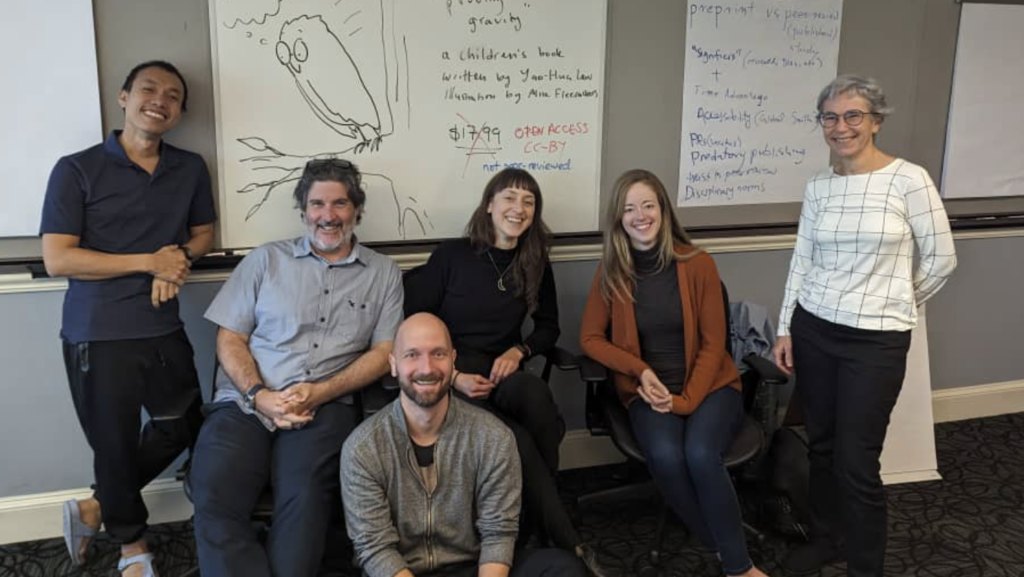

But just as I thought my love affair with preprints was finally coming to a close, I was offered an opportunity to spend four days obsessing about them just a little more. With generous support from the Mellon Foundation—and an incredible team to keep me company—I made my way to Chapel Hill, NC, to attend the 2023 Scholarly Communications Institute (SCI).

This year’s institute brought together five teams of scholars and practitioners to work on projects broadly related to the theme of trust. Our team was led by François van Schalkwyk and included Yao-Hua Law, Mario Malički, Luisa Massarani, Chelsea Ratcliff, and myself. I was excited to collaborate with such a diverse group of journalists and researchers. Our project drew on our experiences working and living in six countries, as well as our shared expertise in scholarly communication, journalism, health communication, meta-research, and (of course) preprints.

Guidelines for Journalists: How to Report on Preprints

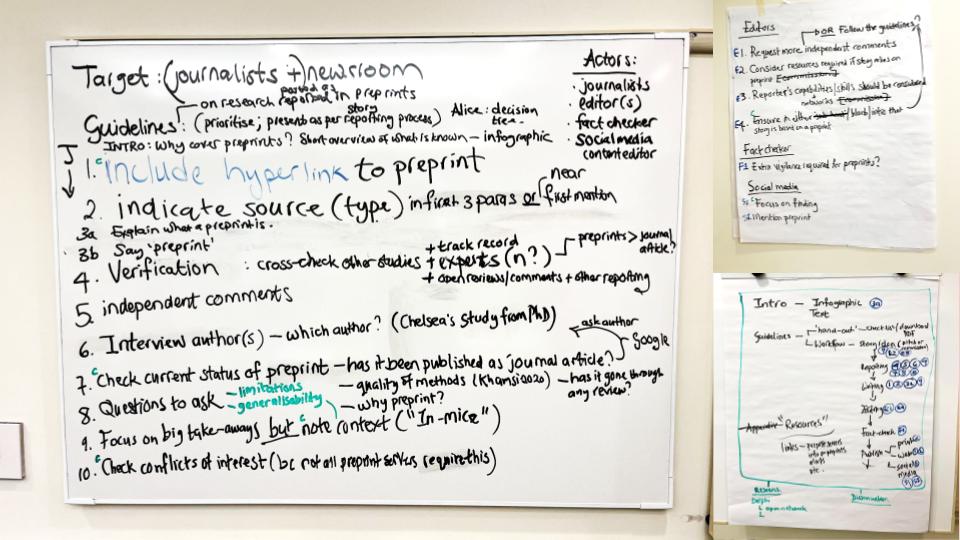

One of our team’s goals for the institute was to develop useful, evidence-based guidelines for reporting on preprints. We began by brainstorming guidelines based on our own research and experiences with preprints, peer review, scholarly communication, and journalism. We then compared this initial set of guidelines to existing recommendations for communicating about preprints. This helped us identify key tips that we might have missed and make sure we were adding something new—not just reinventing the wheel.

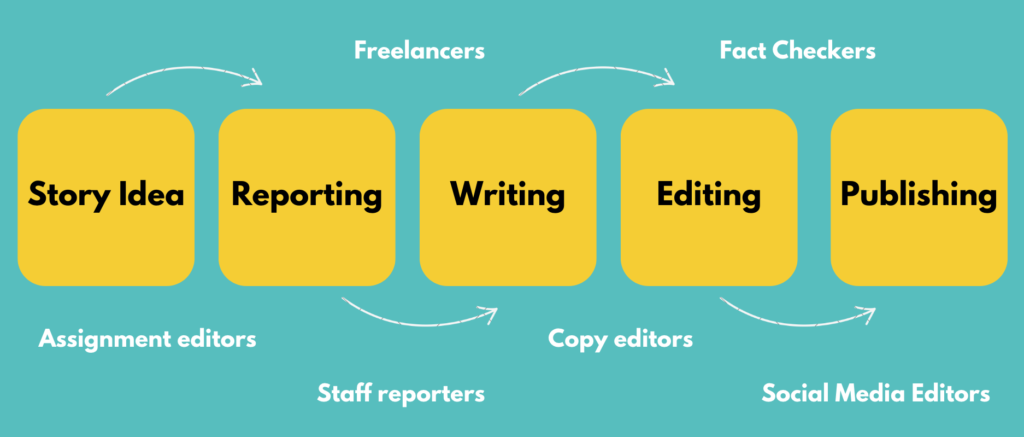

During our review, we noted that some existing recommendations were unrealistic for journalists working in fast-paced newsrooms or without deep expertise in science. We also found that guidelines focused solely on the work of journalists, and not on the editors, fact-checkers, and social media professionals who support (and sometimes control) their work.

With this in mind, we restructured our guidelines to reflect the multiple stages of news production: from generating the idea for a story through to publishing the final version. We plan to refine these working guidelines further by getting feedback from professional journalists, editors, and news professionals in the coming months.

Unanswered Questions and Future Directions: What Else Can We Learn About Preprints in Journalism?

During the institute, we spent a lot of time talking and brainstorming, both within our own team and with other SCI participants. Together, we explored questions about the state of science journalism, the (in)effectiveness of peer review, the future of preprints, the intersections of public engagement and scholarly communication, and more.

Some of these conversations were challenging, but they were also incredibly valuable. As Mario reflected, “It is so incredibly rare in today’s world that you are given an opportunity and support to spend several days in a row with a group of experts around the world to discuss a single topic.” François agreed: “In the hustle and bustle of academic life, the time afforded us was precious and necessary to advance our understanding of scholarly communication.” Luisa noted that the open-ended nature of the discussions was one of the most powerful aspects of the institute.

During our last day together, we reflected on these conversations and the many questions they had raised. We reviewed them as a team and created a list of those we felt were most important to explore in future research, including:

- Does explaining what preprints and peer review are make a difference for how public audiences understand preprint research?

- How does the public understand peer review? Do they trust research more if it has been peer reviewed?

- Are journalists using preprints to cover climate change? Can the patterns we saw during COVID-19 also be seen in the environmental media coverage of preprints?

- What do newsroom editorial policies say about preprints? Do these policies align with what their journalists or editors do in practice?

- What has changed since COVID-19, with respect to how journalists report on preprints?

With about 60 preprint servers, all of which describe and advise preprint use slightly differently, it’s clear that the field needs some unifying guidance. While our team plans to take on some of these questions to support that guidance, we also hope they inspire other scholars to join us. The use of preprints in journalism and scholarly communication continues to grow and change, and I know that our team will be along for the ride.

This blog post may be republished. Please do no edit the piece, and ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on the ScholCommLab blog.

Not “collegial” enough: New study examines unsaid criteria in the tenure process

“Denying a professor tenure, Harvard sparks a debate over ethnic studies,” reads a New York Times story published in January 2020. “After twice being denied tenure, this Naval Academy professor says she is seeking justice,” a more recent headline proclaims. “Academic tenure: In desperate need of reform or of defenders?” asks another.

These headlines offer a taste of the debate that has played out about academic review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) process over the last two years. In the wake of several high-profile cases—most of which involve women or BIPOC scholars who were denied tenure without any clear cause—institutions are under pressure to reevaluate the way in which they make decisions about who gets to stay “in” and who is ultimately pushed out. At the heart of this reckoning are questions about the hidden, implicit values and biases that shape the nature of RPT decisions. In the system that ultimately has the final say about faculty careers, these factors are too often left unsaid.

Over the past 5 years, the ScholCommLab has worked to shed light on these factors and build critical understanding of the nature of the RPT process. Through a series of mixed-method studies, the research team analyzed RPT documents and surveyed scholars from 129 institutions across Canada and the US. Their work has already shed light on many problematic aspects of the RPT process, including an overreliance on flawed metrics, an undervaluation of public forms of scholarship, and unclear and circular definitions of important terms like “impact” and “prestige.”

Now, in its sixth and final study, the research team has turned its attention to another controversial aspect of the RPT process: collegiality.

Collegiality: a double-edged sword in tenure decisions

“Collegiality can be a bit of a double-edged sword,” explains DeDe Dawson, an Associate Librarian at the University of Saskatchewan and lead author of the new study. “It is difficult to assess fairly because it is amorphous and subjective in nature, but if it is not defined it has the potential to be misused to enforce homogeneity, stifle dissent, or as a cover for discrimination.”

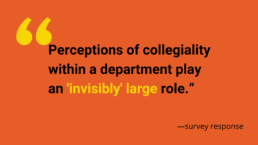

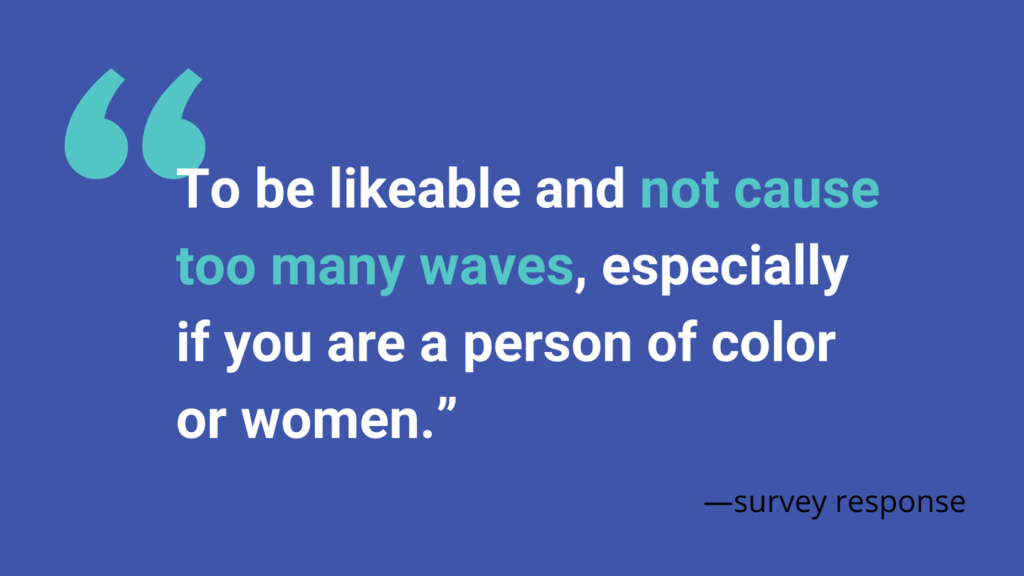

People define the term “collegiality” differently, but at its most basic level, it relates to the quality of relationships. In academic contexts, it’s usually used to describe the ways in which faculty members interact, collaborate, and share responsibilities with each other. Whether collegiality should be formally included in RPT processes is an ongoing controversy that has intensified following the recent high-profile tenure-denial cases. Even when collegiality is not formally included in the RPT process, however, survey data suggests that faculty members consider it to be a factor shaping the RPT decisions at their institutions.

To better understand this apparent contradiction, DeDe worked with Esteban Morales, Erin McKiernan, Lesley Schimanski, Meredith Niles, and Juan Pablo Alperin to examine whether and how “collegiality” featured in a sample of more than 850 RPT documents. The results, published April 6th in PLOS ONE, suggest that collegiality and related terms do appear in at least some RPT documents, particularly those at research-focused universities. When these terms are mentioned, however, the team found that the descriptions tend to be brief at best, providing little information about what “collegiality” actually means or how it would be formally assessed.

Reimagining the future of the RPT process

For DeDe, the lack of clarity surrounding collegiality is concerning: “If this term is left undefined, it could be weaponized to punish those who don’t ‘fit in,’” she says. “It opens it up to be an informal criterion for excluding people based on personal biases.”

But while the findings are bleak, DeDe is not. “I hope our results will motivate departments to begin discussing how best to handle these situations in their own RPT documents and processes,” she says. “Individual faculty members also have a role to play: call out the biases you see playing out on tenure committees. Suggest changes to your RPT standards to recognize and reward collegial behaviours. Work with your colleagues to ensure your department’s RPT documents include clear, equitable reflections of what you value.”

Want to learn more about the RPT project? Read the full study at PLOS ONE or visit the ScholCommLab website to learn more about the RPT project.

Turning policy into practice: The Biomedical Research Open Science Dashboard project

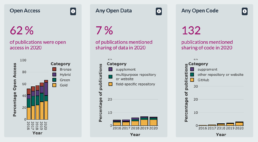

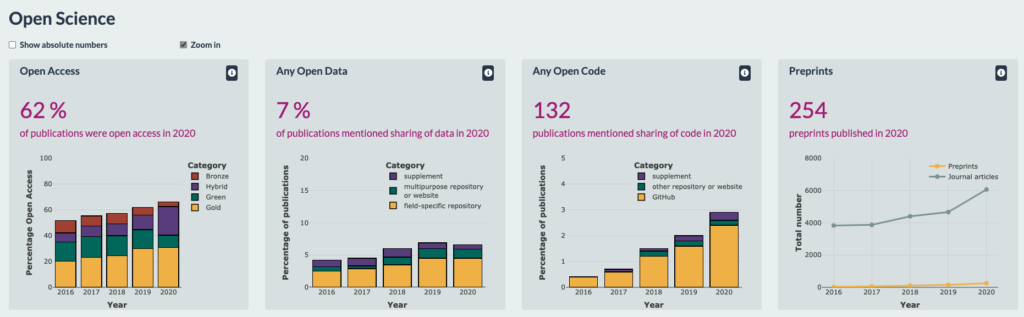

From data sharing mandates to clinical trial registration, Open Science (OS) policies for biomedical research are in no short supply. But ensuring those policies become real-world practices can be a challenge—particularly when there’s no simple way to measure success. Launched in Fall 2021, the Biomedical Research OS Dashboard project hopes to overcome this barrier by helping research organizations track the use of the OS practices that matter most to their communities.

“The reality is that just creating a policy for an open science practice isn't sufficient in terms of its actual implementation,” explains Kelly Cobey, a Scientist at University of Ottawa Heart Institute and primary investigator on the project. “A policy is only as good as the adherence to it, so we want to make sure that we have a way for organizations to actually monitor that compliance.”

The Wellcome-funded project is a collaboration involving 80 researchers and stakeholder participants from 20 institutions around the world. It is led by an international team of researchers that includes ScholCommLab co-directors Stefanie Haustein and Juan Pablo Alperin, as well as leading scholars such as David Moher, Cameron Neylon, Emily Sena, Justin Presseau, Lars Hemkens, Rodrigo Costas, Thed van Leeuwen, Ulrich Dirnagl, and Daniel Strech. The project takes a novel approach that is part research, part action. The goal is to create a community-informed automatic dashboard that will allow institutions to track how consistently members are using recommended OS practices. Beyond measuring progress, the dashboard could be used to identify areas in which more support or training is needed.

“Right now it seems like funders or policymakers come up with a policy and then tell institutions: ‘Okay, you have to do this now.’ Then institutions say: ‘Okay, researchers, you have to do this now.’ But the researchers are left in a situation where they may not be aware of why or how to comply with the OS practice and may not feel supported,” Cobey explains, “No one coaches them through it. That's why you see the gap between policy and implementation.”

The project builds on the foundations laid out by Charité’s custom OS dashboard and Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative’s (COKI) open access (OA) dashboard. It will monitor a range of OS practices, much like the Charité dashboard, but will be developed, tested, and refined to reflect those practices that are seen as most valuable to stakeholders at biomedical institutions across the world. It’s being created by the community, for the community.

“A lot of times people just get an idea and make a prototype, but after investing all that time and money and funding, they find that the tool doesn't resonate with the community,” Cobey says, “We're trying to circumvent that by involving them in the process and the user-design.”

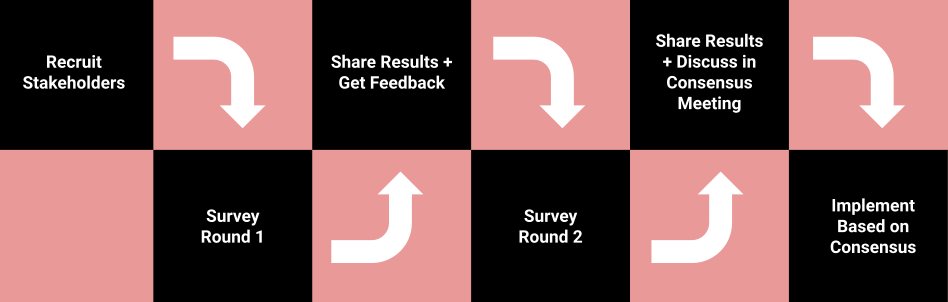

To identify the OS practices that should be included in the final dashboard, the project employs what Cobey calls an "integrated knowledge mobilization" approach. This includes using the Delphi survey method, which allows researchers to iteratively gather and integrate feedback from stakeholders throughout the research and prototyping process. This process involves a cycle of surveying stakeholders, synthesizing key findings and presenting them to participants, gathering feedback, and finally integrating that feedback into the next set of survey questions. The Biomedical Research OS Dashboard project team is currently knee-deep in the survey cycle, but hopes to publish a preprint of the final results in summer 2022.

To ensure the final dashboard is useful across multiple biomedical research contexts, Delphi participants were recruited to support broad representation of geographies, genders, and career stages. Cobey says that the diversity of participating stakeholders has already yielded important insights. “It's been really eye opening,” she says, “you have all these people with good intentions thinking about public accessibility, but not every intention is feasible in every local context.”

Take, for example, the question of whether to include Open Access (OA) publishing in the dashboard. While OA compliance seemed like an obvious activity to include, Cobey says deciding on the right metric to track was complicated by international differences in policies and resources. In line with the recommendations laid out in Plan S, many European participants indicated in round 1 and 2 surveys that they wanted to track Gold OA (i.e., publication of articles in openly available journals). But scholars from regions with different OA policies, such as Nigeria and Latin America, felt that this would be inequitable. In biomedicine, publishing Gold OA typically requires researchers to pay high Article Processing Charges (APCs), which can be inaccessible for scholars with fewer resources. Scholars from these regions made it clear that they would not want to be benchmarked against the European standard.

“Had I, from here in Canada, just come up with a metric, I might not have had that perspective,” Cobey reflects. “That's why I think it's so important to have a diversity of views.”

“As researchers and research institutions, there's the responsibility to maintain these best practices. We’re excited to provide a tool that makes that responsibility a little bit easier.”

Kelly Cobey

It’s still early days for the project, and there’s lots of work to be done. But Cobey is hopeful about what lies ahead. “We know that Open Science practices can increase the usability of research, support reproducibility, and reduce bias” she says. “At the end of the day, if we don't publish our results, or we report them in a way that's biased, it's unethical. As researchers and research institutions, there's the responsibility to maintain these best practices. We’re excited to provide a tool that makes that responsibility a little bit easier.”

To stay up to date with the Biomedical Research OS Dashboard project, sign up for the ScholCommLab newsletter.

Double tenure: ScholCommLab co-directors celebrate a career milestone together

Six years ago, Juan Pablo Alperin and Stefanie Haustein sat down at a bar in Amsterdam after a full day of participating in a conference. They came for a drink and an opportunity to connect over shared interests, but they left with an ambitious plan that would change both of their careers. On the backs of beer napkins, a project aimed at understanding the societal impact of research with the help of altmetrics started to take shape. The gin-and-tonic-inspired grant was successful, and, with that project, the ScholCommLab was born.

At the time, Juan was a newly minted Assistant Professor at Simon Fraser University and Stefanie was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Montreal. More than half a decade after embarking on that first journey together, the two lab co-directors are celebrating a second career-defining moment: tenure.

“Being tenured is a huge milestone,” says Stefanie, who became an Associate Professor at University of Ottawa, School of Information Studies (ÉSIS) on May 1, 2021. “I felt so much excitement and relief when I received the (anonymized) letters of the external reviewers—they were extremely generous and kind.”

“It is great to be unencumbered from expectations and from any sense of having to prove myself,” agrees Juan, an Associate Professor at Simon Fraser University’s Publishing Program as of September 1. “That feeling of freedom manifests itself whenever I decide to accept or turn down an invitation or opportunity. In the last few months, I have always been more certain that if I say yes or no, it is because of my own interests, and not out of a sense of what I should be doing.”

“That feeling of freedom manifests itself whenever I decide to accept or turn down an invitation or opportunity. In the last few months, I have always been more certain that if I say yes or no, it is because of my own interests, and not out of a sense of what I should be doing.”

Juan Pablo Alperin

The two co-directors celebrate this milestone from a place of transition—Stefanie returning from maternity leave, Juan preparing for his first sabbatical. Both look forward to reconnecting with friends and colleagues and continuing the work that has brought them to this moment.

“I am excited to continue working on existing grants on data citations (funded by Sloan) and metrics literacies (funded by SSHRC) and one on open science practices that we recently received from the Wellcome Trust,” Stefanie says. “But what I am most excited about is seeing the Ottawa team and students face to face again—it’s been way too long and I miss everyone!”

“I am using this opportunity to reconnect with my colleagues in Latin America,” Juan explains. “There is a lot of interest in the region to develop Open Science policy, and so I have been reaching out to everyone I know to see how I can be most helpful.” He’s also been applying for several major grants, with the hope of returning from sabbatical to a very active lab.

While both are grateful to start this next chapter of their careers, neither expects that their new title will change the nature of their work.

“I’ve never been a really strategic person, so my research has always focused on what I am most interested in rather than what looks good on my CV,” Stefanie explains. “I don’t anticipate that having tenure will actually influence how I work or what I work on.”

“I became a tenured professor doing the things I love, not doing what others wanted me to do,” Juan explains. For him, the key to tenure was “to think about it enough to make sure I participated in and accomplished the things I wanted to showcase to the committee, but not enough that I lost sight of myself while trying to tick boxes.” He adds that, to get tenure, “You want to do you.”

Three questions with… Mario!

Our lab is growing! In our Three Questions series, we’re profiling each of our members and the amazing work they’re doing.

Our latest post features Mario Malički, a former visiting scholar and ongoing collaborator at the ScholCommLab. Currently working as a postdoc at METRICS Stanford University, Mario is also a Co-Editor-in-Chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review. In this post, he reflects on some of the proudest moments of his career and shares why he’s most excited about the moments yet to come.

Q#1 What are you working on at the lab?

Joseph Costello, Juan Pablo Alperin, Lauren Maggio, and I recently finished an analysis of single comments left for bioRxiv preprints. And I have recently proposed a template for peer review which I will improve based on the feedback from the lab. It is my hope that such a template will help both young and established researchers be more honest in acknowledging and understanding their scholarly strengths, and how they can best help those whose papers they review. The template is supposed to support researchers in conducting and writing their review reports, and help them focus on essential items they should try to address.

Q#2 Tell us about a recent paper, presentation, or project you’re proud of.

I am moving in the mid-career researcher stage and have been recently reflecting on the 30+ papers I have co-authored in my lifetime. I remember the pride I felt the first time I designed and wrote a full study from scratch that did not involve my PhD mentors. I also remember the sense of accomplishment I experienced when I finally finalized a project on duplicate publications after five years of work, as well as the satisfaction of posting my last preprint that dealt with preprint server policies and research integrity. Lately, however, I am most proud that I have realized what I want to focus on in the next period of my career: increasing the transparency of peer review. I believe it’s time we start making it clear when peer review predominantly provides a seal of approval for a study well done vs when it greatly improves the study’s reporting, analysis, or interpretation of results.

I am moving in the mid-career researcher stage and have been recently reflecting on the 30+ papers I have co-authored in my lifetime... I have realized what I want to focus on in the next period of my career: increasing the transparency of peer review.

Q#3 What’s the best (or worst) piece of advice you’ve ever received?

My mum worked as a nurse, so there is a trifecta of advice I always think of when someone asks about advice I’ve received. Although I remember them in series, I cannot be sure she offered these words of advice one after the other—maybe they just accumulated in my mind over time. The first one was to never use fireworks (as she would treat so many kids who had been badly hurt by them), the second was to use protection (as you don’t want to regret your choices), and the third was to live with someone for at least a year before you marry them.

The worst advice (I got this twice actually) was that I should back down on my principles if I wanted to more easily advance in academia and not offend senior or emeritus professors. Even though I didn’t take the advice, I am glad those words were spoken to me, as they made me realize under which conditions and with whom I want to continue working as a researcher.

Find Mario on Twitter at @Mario_Malicki

Three questions with… Kathleen!

Our lab is growing! In our Three Questions series, we’re profiling each of our members and the amazing work they’re doing.

This week’s post features Kathleen Gregory, a postdoctoral researcher exploring data citation practices—and the newest member of the ScholCommLab. In this interview, she shares her biggest questions about how researchers use data and offers one simple tip to help with everything from paper writing to home decorating.

Q#1 What are you working on at the lab?

I am a postdoctoral researcher working (remotely from the Netherlands) on the Meaningful Data Counts project with Stefanie Haustein, Isabella Peters, and Anton Ninkov.

Our project maps out current practices of data sharing, data reuse, and data citation across disciplines. I am especially excited about digging into the ‘why’ behind these practices: Why do researchers cite (or not cite) data? Which ‘data uses’ are not cited? How does this all relate to how researchers cite other things—like academic literature? Which patterns exist across and within disciplinary fields, data types, research topics...? I could go on, but I will stop there.

Q#2 Tell us about a recent paper, presentation, or project you’re proud of.

I am very proud of my doctoral dissertation, which was awarded a cum laude designation that is not often given out in the Netherlands. It is both exciting and a bit strange to have four rewarding, yet exhausting, years of my life packaged neatly into a book.

I am also excited about a book chapter that I am working on with Sally Wyatt, Paul Groth, and Andrea Scharnhorst on interdisciplinarity. The chapter looks at how conflicting ideas about a common concept (in this case, ‘users’ and ‘uses’ of technology) can provide common ground in interdisciplinary research.

Q#3 What’s the best (or worst) piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Can I list two?

Whenever I was trying to decide to go for something (e.g. a new job, trying something new in school), my mom would say: “Does it hurt you or someone else? If not, it is probably an opportunity.” On the whole this has been good advice, but it has also been a bit of a double-edged sword as I sometimes end up with too many “opportunities.”

My second piece of advice comes from Thoreau: “Simplify, simplify, simplify.” This helps to counter the problem of too many opportunities. It is also helpful in writing academic papers and home decorating.

Find out more about Kathleen on her website or follow her on Twitter at @gregory_km.

Three questions with… Rukhsana!

Our lab is growing! In our Three Questions series, we’re profiling each of our members and the amazing work they’re doing.

Today’s post features Rukhsana Ahmed, an Associate Professor and Department Chair in the Department of Communication at the University at Albany, State University of New York. In this interview, she tells us about her work as a research associate at the ScholCommLab and offers words of wisdom for finishing what you start.

Q#1 What are you working on at the lab?

I recently collaborated with Alice Fleerackers, Michelle Riedlinger, Laura Moorhead, and Juan Pablo Alperin on a paper investigating how preprints—unreviewed research studies—about COVID-19 were portrayed in online media stories. We found that about half of media stories mentioning preprints did not communicate the unverified nature of the research.

That paper was part of our larger project, “Sharing Health Research: The Circulation of Reliable Health Science in a Changing Media Landscape,” which focuses on a range of aspects of online health communication. In the next phase of that project, I am planning to take a deep dive into COVID-19 vaccine information seeking and sharing pathways among racial and ethnic minority communities. This next study focuses on the ways in which these groups obtain and use evidence-based health information to make vaccination decisions. I’m also curious about the communication channels used by health care providers to share COVID-19 vaccine information with racial and ethnic minority communities. Understanding the communication strategies public health professionals use to establish trust and credibility when communicating such messages to these groups is important for improving public health risk communication.

Q#2 Tell us about a recent paper, presentation, or project you’re proud of.

Right now, I’m working with a team of student-faculty researchers at UAlbany to explore how multi-lingual YouTube videos can be used to connect people with limited English proficiency (LEP) with essential COVID-19 information. By providing content that is linguistically and culturally relevant, we see these videos—available in Arabic, Bangla, Chinese, and Spanish—as crucial to addressing the communication inequalities among LEP groups. This project is still in the works—we’re wrapping up the pre- and post-test surveys and launching the post-test-only surveys and interviews—but I’m very proud of how far we’ve come. I’m excited to see how our research findings will help identify levers of change within language communities and recommendations to providers for how to produce audiovisual materials that encourage vaccination.

Q#3 What’s the best (or worst) piece of advice you’ve ever received?

One of the best pieces of advice I received was from my doctoral advisor, who said: “A good project is a done project.” I took it by heart and lived by it, and in the spirit of paying it forward, I also give my students this piece of advice. It has helped me stay focused and on task on the projects I work on. I think this advice also helps students to see through what they start by encouraging them to devise, and stick to, a plan for completion. For researchers who are perfectionists and may get hung up on working through the small details, this advice can help them to keep the big picture in mind and make progress in their work.

Follow Rukhsana on Twitter at @RAUAlbany.

Three questions with… Alice!

Our lab is growing! In our Three Questions series, we’re profiling each of our members and the amazing work they’re doing.

In this week’s post, PhD student and writer Alice Fleerackers shares her thoughts on managing the ScholCommLab blog, learning through collaboration, and letting commitments go.

Q#1 What are you working on at the lab?

The TLDR version? I communicate research and I research communication.

The longer version is that I wear a lot of hats at the lab—and one of them is managing this blog! This part of my job can be a little awkward at times—“interviewing” yourself for a blog post is definitely not something I'd recommend—but it can also be super rewarding. I’ve loved getting to know all of our members a little better through the blog, especially via this series. I feel like I learn something new with every post.

In addition to my communications hat, I’m a PhD student at the lab. My research interests are pretty broad, and they’ve led me to a bunch of interesting projects at the intersections of health communication, digital journalism, scholarly communication, and science communication. One of the best things about the lab is how different everyone’s interests are. As someone who is constantly curious, collaborating on other people’s projects has been an amazing way to explore.

Q#2 Tell us about a recent paper, presentation, or project you’re proud of.

I’m really proud of our recent paper in Health Communication, which came out in early January. For that project, I worked with Michelle Riedlinger, Laura Moorhead, Rukhsana Ahmed, and Juan Pablo Alperin to analyze how COVID-19-related preprints—unreviewed research papers—were portrayed in online media stories published during the early months of the pandemic.

I was surprised to find that about half of the media stories we analyzed didn’t communicate the unverified nature of the preprints they cited. But I was even more surprised to see how widely our findings resonated. This paper has sparked conversations about preprints among journalists, scientists, news readers, and many others. I’m excited to see where those conversations might lead in the future.

Q#3 What’s the best (or worst) piece of advice you’ve ever received?

When I was in my early(er) 20s, I was a web editor for a local magazine called SAD Mag. It was a really rewarding gig—I got to work with great people, support emerging writers, and review theatre, dance, and art shows (all for free!). I even had a chance to interview my teenage hero, Dan Savage.

But it was also a volunteer gig, and one that I eventually no longer had time for. For months, I delayed leaving, terrified to tell my creative director that I had to move on. I shouldn’t have. In our parting conversation, she gave me a piece of advice that I will always remember: “If something is no longer serving you, let it go.”

That conversation taught me that there are only so many hours in a day. It’s up to us to use them wisely.

Read more by Alice at her online writing portfolio or find her on Twitter at @FleerackersA.

Three questions with… Lisa!

Our lab is growing! In our Three Questions series, we’re profiling each of our members and the amazing work they’re doing.

This week’s post features Lisa Matthias, a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of North American Studies at Freie Universität Berlin. After joining the lab in Spring 2019 to lead a project on opioid science in the news, Lisa stayed on to become the ScholCommLab’s official “perennial” visiting scholar.

Here, she tells us all about her work investigating scholarly publishing fees and vanishing journals. She also offers advice for making it through your first teaching semester alive.

Q#1 What are you working on at the lab?

I would say my work at the lab is currently on hold as I’m focusing on finishing my PhD. The last project I was involved in was a revamp of the 2015 oligopoly paper, where Stefanie Haustein, Philippe Mongeon, LeighAnn Butler, Marc-André Simard, and I were working to determine the dominant scholarly publishers, based on article volume, and to examine how much revenue they make from article processing charges. The team is still working on it now, so stay tuned for that.

Q#2 Tell us about a recent paper, presentation, or project you’re proud of.

Mikael Laakso, Najko Jahn, and I recently published a paper about vanished open access journals that got quite a bit of attention when we first shared the preprint. We found that between 2000 and 2019, 174 journals vanished from the web due to insufficient preservation. I was really excited to see the positive responses from the scholarly communications community and that some of the key organizations in this space have since come together to tackle the issue of affordable preservation of open access journals to prevent the loss of more journals.

Q#3 What’s the best (or worst) piece of advice you’ve ever received?

I got to teach my first seminar last semester, and after the fourth session—because I have no patience with myself—I asked a friend if teaching was ever going to get any easier. He told me that the first time for any seminar is just about surviving. I would remind myself of this before and after each session and it really changed how I approached teaching. His advice reassured me that this was a learning experience for me too. That brought me so much calm.

Find Lisa on Twitter at @l_matthia.

Three questions with… Cecilia!

Our lab is growing! In our Three Questions series, we’re profiling each of our members and the amazing work they’re doing.

In this week’s post we’re highlighting Cecilia Rozemblum, a PhD student in the ScholCommLab based at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (UNLP), Argentina. With two degrees under her belt already—one in librarianship and documentation—she’s excited to be almost done her third. In this post, she tells us more about her research on altmetrics and scholarly impact, and why sometimes the best advice can also be the scariest.

Q#1 What are you working on at the lab?

I’m writing my PhD thesis under Juan Pablo Alperin’s direction, and he is very patient, because I've been doing it for 3 years! I hope this will be the last and that I will obtain my degree at the end of 2021. My dissertation is about altmetrics and the diversity of ways to identify the visibility and impact of academic journals, especially those based in Latin America and focused on social sciences.

Q#2 Tell us about a recent paper, presentation, or project you’re proud of.

I recently finished a paper with two colleagues, Juan Pablo and Carolina Unzurrunzaga, which we decided to post on Zenodo, a preprint repository. It offers a preview of some results from my doctoral research. This was my first experience authoring a preprint and I feel so excited because it has had such a wide impact already, with many page views and downloads. I hope that this research will become a real paper soon.

Q#3 What’s the best (or worst) piece of advice you’ve ever received?

I've received two interesting pieces of advice. One from a colleague, which is very useful: "NEVER write an email when angry." If you feel this way, let 24 hours pass and then write the email, when you’re more calm.

The second, which is almost scary, came from my dad: "Pay attention." To what? In general, to everything!! This may seem like too much but this advice is also so wise. Pay attention to the nice things and to the not so nice things too.

Find out more about Cecilia on Twitter or at her Memoria Académica profile [in Spanish].