Swiss Year of Scientometrics Lecture: Opportunities and Challenges of Scientometrics–Part I

This blog post is the first in a four part series based on the keynote presentation by Stefanie Haustein at the Swiss Year of Scientometrics lecture and workshop series at ETH Zurich on June 7, 2023. Stay tuned for our next post, in which we’ll share opportunities and challenges of scientometrics, with a focus on the diversification of research outputs.

Thank you to David Johann and Annette Guignard at ETH Library for inviting me to open this lecture series for the Swiss Year of Scientometrics.

In the hope of inspiring some interesting discussions, my goal is to provide you with a very broad overview of a number of opportunities and challenges of scientometrics, with a focus on the diversification of data sources and areas of application.

I will talk about how the data sources for bibliometric analysis are becoming more diverse, both from the perspective of data providers and the types of research outputs considered.

With respect to new areas where scientometrics can generate an evidence base, I will briefly address library collection management, open science monitoring as well as the responsible use of scholarly metrics.

I’ll conclude the talk with some reflections on what I consider the main opportunities and challenges of scientometrics today.

Diversification of data providers

The number of companies providing bibliometric data has really exploded in recent years. Some of you might still remember the times when the Web of Science was the only option for citation analysis.

While closed infrastructure and proprietary data sources were the norm for decades, we now see an explosion of open infrastructure developments. In my opinion, a particularly exciting development is the flip from closed to open infrastructure—when OurResearch took over Microsoft Academic Graph (MAG) and turned it into OpenAlex.

The open players—OpenAlex, Crossref and DataCite—are committed to a set of guidelines called the Principles of Open Scholarly Infrastructure (POSI). These guidelines prescribe, for example, that the infrastructures should be steered collectively by the community, not by lobbyists, and that revenue generation is mission oriented and based on services, not on selling data. In fact, all data and software of these organizations should be open and not patentable.

OpenAlex

When Microsoft decided to cease operations, the non-profit OurResearch with support from a $4.5 million grant from Arcadia decided to further develop MAG and turn it into open infrastructure that is accessible via API, a data dump, and (since very recently) a user interface.

Apart from it being open and free to reuse for any purposes, OpenAlex’s unique selling point is certainly its coverage and size, making it a great potential source for more inclusive bibliometric analyses.

Approaching its metadata from a bibliometric perspective, OpenAlex provides the basic building blocks for the analysis of research outputs and impact. OpenAlex is a heterogeneous directed graph linking research outputs, called Works, as well as information about who published them, where they were published, their research area, and even who funded it.

Since OpenAlex was only recently launched, we don’t know much yet about the feasibility for scientometric analyses. So I want to explore two crucial metadata elements in a bit more detail: institutional affiliations and disciplines.

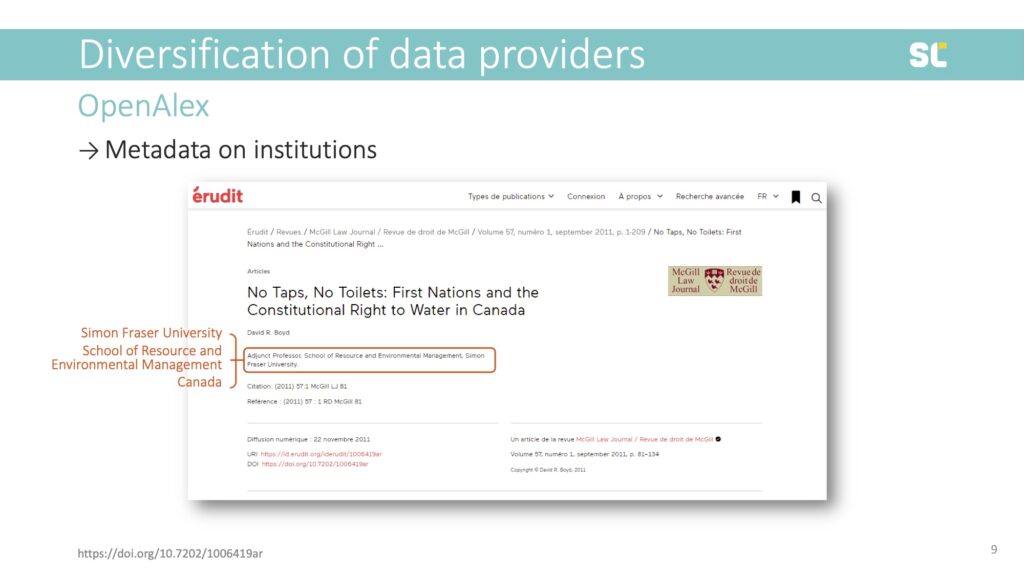

Author addresses on academic publications provide us with information about their institution. In this example, you see that this author was affiliated with Simon Fraser University in Canada:

These elements form the basic building blocks for an institutional analysis on the meso and macro levels of bibliometric analysis, providing us with the university, department, and country of the author.

OpenAlex uses an algorithm to link institutional information to the Persistent Identifier from the Research Organization Registry (ROR ID), combining metadata from Crossref, PubMed, ROR, Microsoft Academic Graph, and publisher websites. Through this enriching process, every institution in OpenAlex is supposed to have a ROR ID.

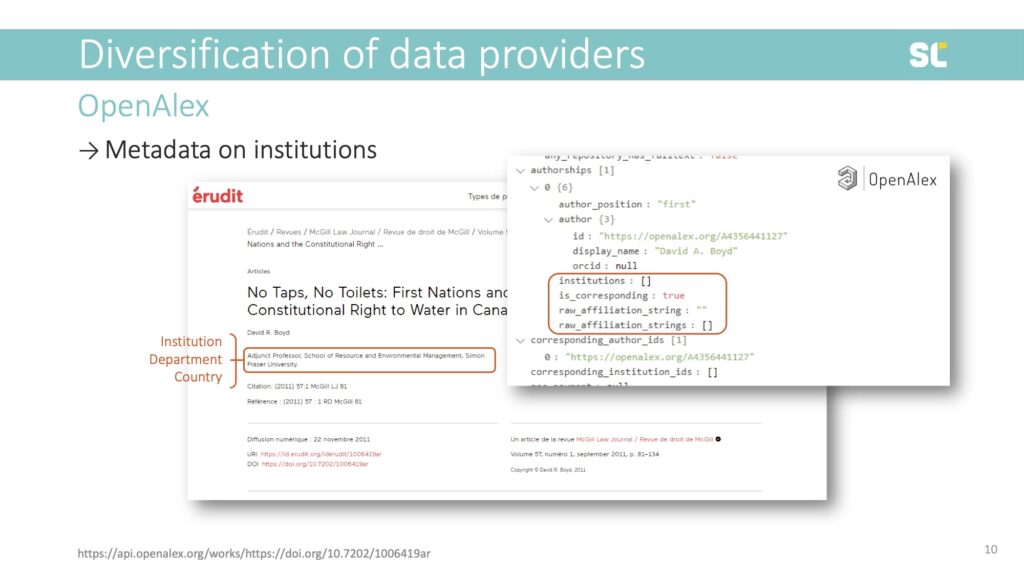

In this example, however, we see that OpenAlex does not have any institutional metadata even though the original publication did:

By the way, the same is true for this paper in Dimensions, which likely means that the publisher did not provide institutional information to Crossref.

So what does this mean bibliometrically? While this article could be tracked via DOI, author name, or journal, it would not be included in any analysis that relies on country or institution, either as a method of retrieval, or unit of analysis. This paper would neither count as an output for Canada nor Simon Fraser University because the metadata is missing.

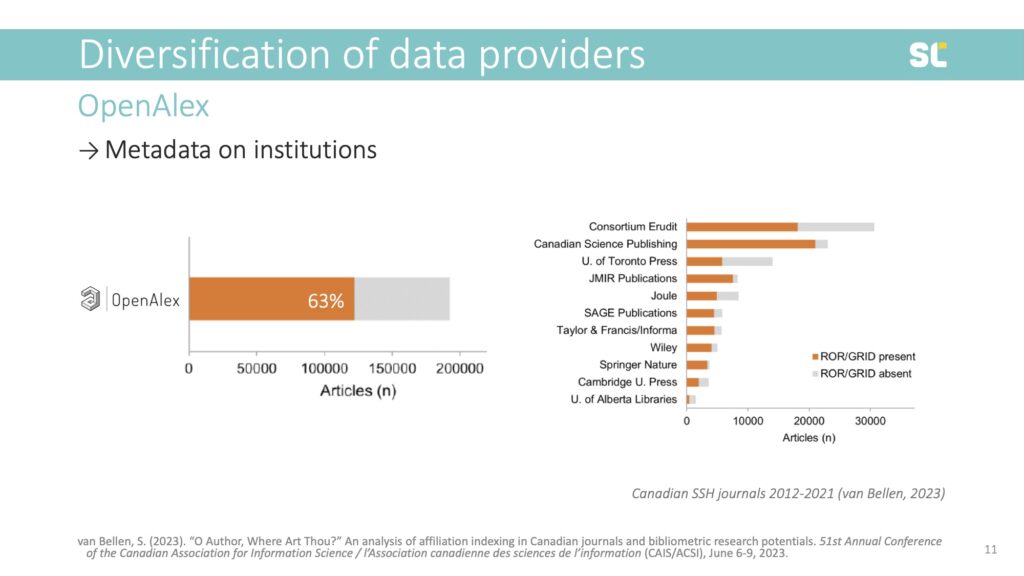

My colleague Simon van Bellen at the Canadian journal platform Érudit analyzed the presence of RORs in OpenAlex for all papers published in Canadian social sciences and humanities journals from 2012 to 2021. He found that 63% of papers were retrievable via ROR ID, which means that over one third of papers did not have an institutional address.

What is even more alarming is the huge differences between publishers. For example, while institutional metadata was present in 90% of journals published by Springer-Nature, the non-profit Consortium Erudit had institutional metadata in only 59% of their published papers.

This means that the metadata that publishers provide affects the visibility of these papers in bibliometric analyses using OpenAlex or Dimensions. So even if these larger more inclusive databases now cover more outputs, they don’t necessarily translate into more and more diverse outputs on the institutional or country level.

Disciplinary metadata is particularly important in scientometric analyses for benchmarking and normalizing field-specific publication and citation practices.

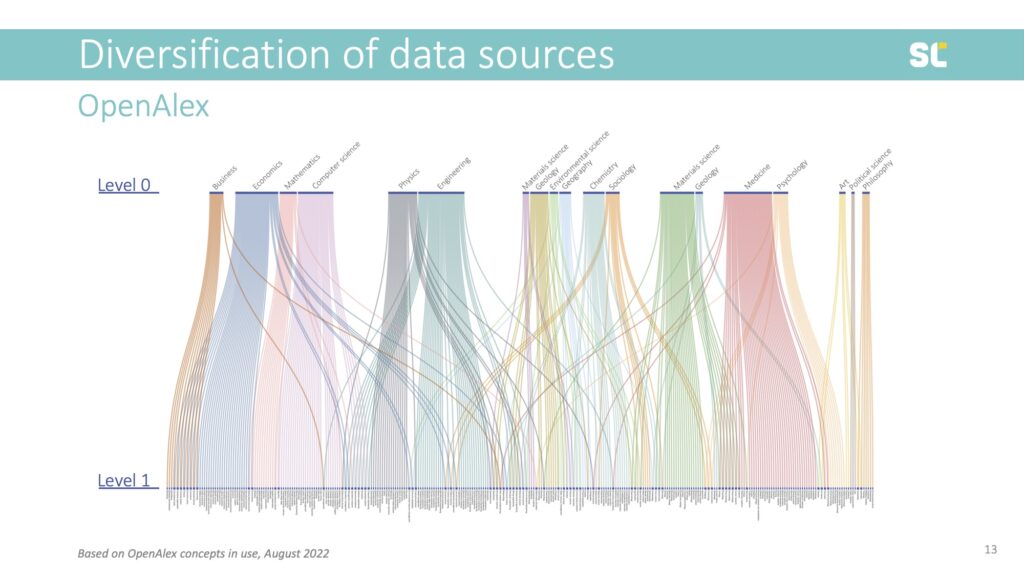

OpenAlex uses Wikidata concepts for subject indexing. Concepts are assigned automatically based on title, abstract and journal, conference or book title. Concepts are hierarchical with five levels for a total of 65,000 concepts.

This classification system is a modified version from Microsoft Academic’s fields of study, which has been criticized by Sven Hug and colleagues (2017) who concluded that it would not make a good base for bibliometric indicators due to the dynamic number of fields and inconsistent hierarchies.

Although they are made to look like a true hierarchical classification system with an astonishing number of classes, concepts do NOT fulfill the properties of a regular classification system. For example, in the slide below, you see the first two hierarchies and that many of these have two parent classes.

Moreover, the quality of some index terms is questionable and so are some of the hierarchical relationships. For instance, Literature L1 (under L0 Art) has 391 level 2 classes, including geographical classes (Italian literature, Scottish literature), classes about literary movements (modernism, absurdism) or literary criticism (reception theory), genres (detective fiction, travel writing) as well as concepts that certainly shouldn’t be found on the third hierarchy level, or not even be classes at all—such as individual Shakespeare plays like Hamlet, Star Trek, or Harry Potter[1].

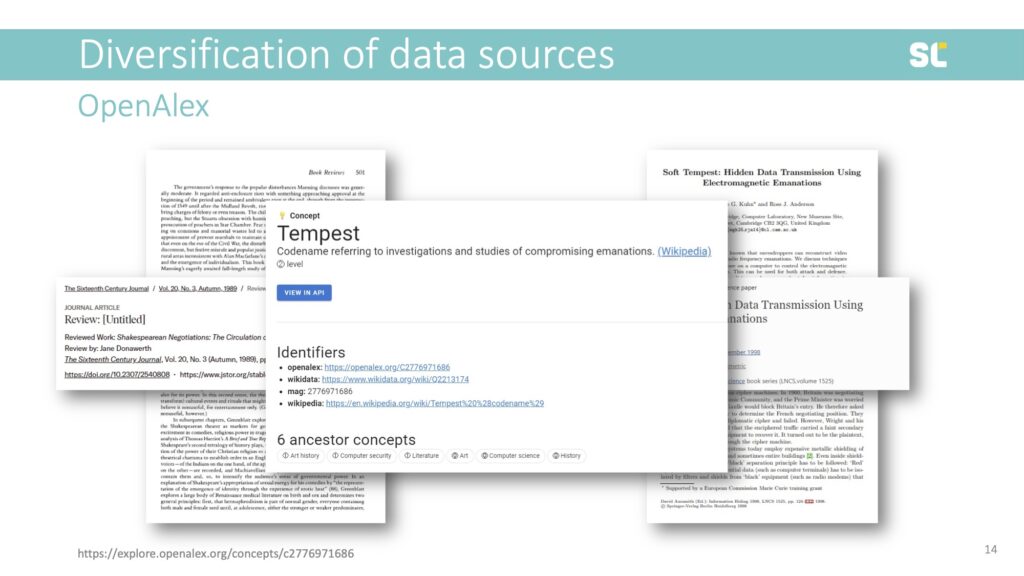

Another severe issue is also that there is no vocabulary control in the OpenAlex concepts. For example, homonyms are not distinguished. As shown in the slide below, this book review published in the Sixteenth Century Journal and this conference paper published in a Lecture Notes in Computer Science book series are tagged with the same concept.

“Tempest” is a Level 2 term (third level of hierarchy) and a subordinate class of Literature, Art History, and Computer Security. The Tempest is a play by Shakespeare but also an acronym for “Telecommunications Electronics Materials Protected from Emanating Spurious Transmissions,” which is the US National Security Agency’s specification for protecting against data theft through the interception of electromagnetic radiation.

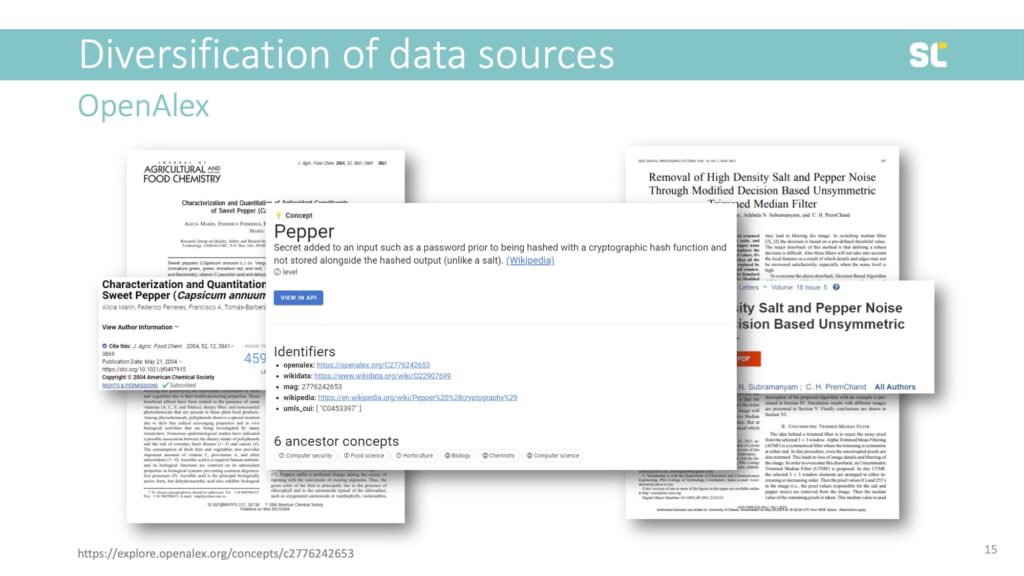

Another example are these two papers, one published in a journal called Agricultural and Food Chemistry and one in IEEE Signal Processing Letters.

“Pepper” is a Level 2 class, with three different parent classes: Food Science, Horticulture, and Computer Security. This shows that the concepts in OpenAlex are highly problematic and should at this point not be used for bibliometric analyses.

However, I want to emphasize the recent launch of OpenAlex and that in my opinion it provides a huge opportunity to build an open, community owned system that can be more inclusive if metadata quality and completeness are addressed. I think that we need to invest in this open infrastructure and contribute to improving quality as a community.

Elsevier

I now want to talk about Elsevier, who has been a bibliometric data provider through Scopus for several decades. But instead of talking about Scopus as such, I want to highlight how it has become an information analytics business that has been collecting metadata of scholarly outputs for almost 150 years.

I also want to highlight the aspect of Elsevier being a highly profitable business. As Sarah Lamdan highlights in her recent book Data Cartels, “Elsevier focuses on crunching academic researchers’ data in new ways to make money off the research process.”

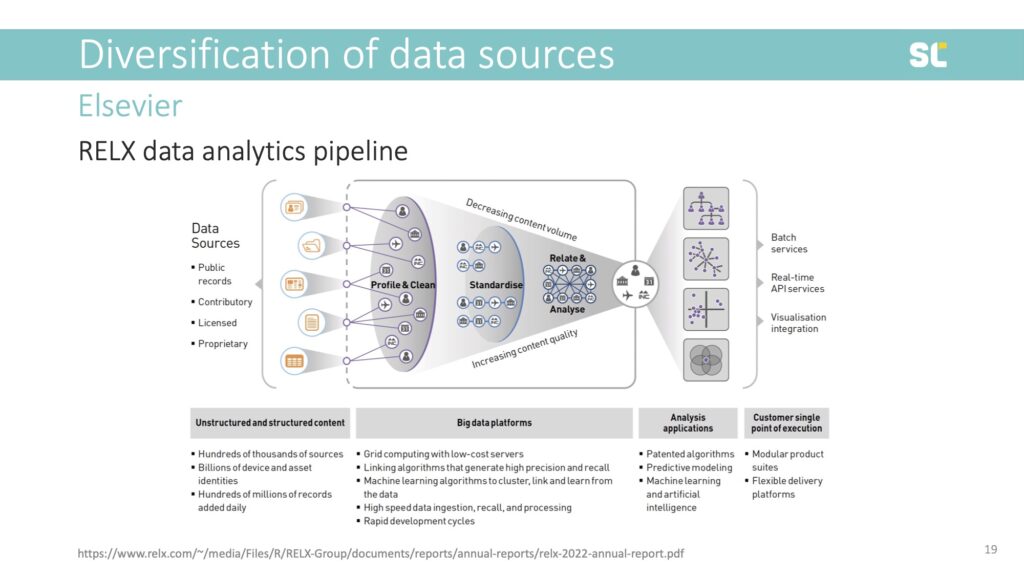

Elsevier is part of the RELX Group, representing the Scientific, Technical, and Medical segment. What is clear is that it is no longer just a publisher, it’s a data analytics company. Databases, tools, and electronic reference generate almost as much revenue as publishing.

But it’s because of the wealth of information and decades of electronic and online data collection that Elsevier has become so powerful. They have built an incredible data analytics pipeline by collecting data and acquiring tools and platforms that capture the entire research cycle and research evaluation process (see below).

This would be incredible infrastructure for the academic community but because Elsevier is a private company and not a community organization working for the public good, it does what it’s supposed to do: “monetize the entire knowledge production cycle” (Lamdan, 2023, p. 53) and sell raw data from content created by the academic community and data about people who access this content, back to its customers in a plethora of services.

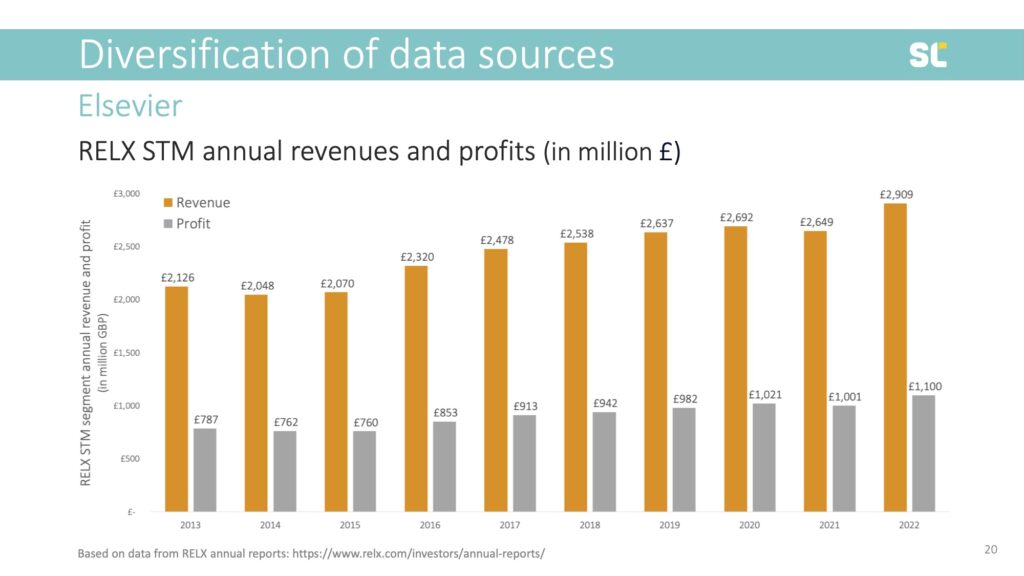

Last year alone, Elsevier created 2.9 billion pounds in revenue and 1.1 billion pounds profit. In the last 10 years, as shown below, their profit was 9.1 billion pounds. That’s almost 12 billion Swiss franc or 11.3 billion euros.

Elsevier’s profit margin is very stable, at 38% annually, because most of their content is provided for free, be it authors’ manuscripts, peer review, or the digital traces left by those accessing the content. This means that for every 1,000 euro spent by the scholarly community on article processing charges, journals or database access, 380 euro leaves the system to pay shareholders—people that were smart enough to invest in RELX stock.

Looking ahead, Elsevier is expecting to grow and further increase profits.

From a scientometric perspective, Elsevier controls and maintains a wealth of rich, connected metadata about the entire research lifecycle. For the academic community, this comes at unsustainable costs. It makes one think what could be possible if just a fraction of these amounts would go into supporting open infrastructure, both for publishing and scientometric analyses.

Stay tuned for our next post, in which we’ll share opportunities and challenges of scientometrics, with a focus on the diversification of research outputs. Check out the Swiss Year of Scientometrics blog for recordings of Stefanie’s lecture and workshop.

References

Hug, S.E., Ochsner, M. & Brändle, M.P. Citation analysis with microsoft academic. Scientometrics 111, 371–378 (2017).

Lamden, S. Data Cartels: The Companies That Control and Monopolize Our Information, Stanford University Press (2023).

van Bellen, S. “O Author, Where Art Thou?” An Analysis of Affiliation Indexing in Canadian Journals and Bibliometric Research Potential. CAIS-ACSI 2023, Canada. Zenodo (2023).

Footnotes

[1] Special thanks to University of Ottawa ÉSIS students Alexandra Auger, Karinne M., and Caroline Plante for analyzing the OpenAlex concepts Literature class in detail.