Keynote talk: The most innovative methods are sometimes the simplest

Keynote presented by Juan Pablo Alperin at the 13th annual EBSI-SIS Information Science Symposium on April 28, 2021.

Thank you very much for this invitation.

Before I begin, let me begin by acknowledging that I am speaking to you from the traditional unceded territories of the Coast Salish people, including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ təməxʷ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. I am incredibly fortunate to have the opportunity to live, work, and take in the beauty of these lands on which I am an uninvited guest.

I want to continue, by way of introduction, to tell you that it is a real treat to have an opportunity to speak to this distinguished group of library and information science students. You probably don’t know this, but although my work intersects with information science more than any other discipline, I work in a Publishing Studies program, which offers a Masters of Publishing degree that is oriented towards the publishing profession. This means I have very few opportunities to address graduate students who might, perhaps, I hope, be at least slightly interested in my research. The MPub students who I teach get to experience a very different side of me—one that discusses the issues I see with technologies, the Web, and how both of those things affect the content industries. While there are graduate students on my team at the ScholCommLab, it is not quite the same thrill as having a whole crowd of you to address directly.

And so, when I accepted to give this address, I decided I would use it to get out of my system the kind of advice that I would have the opportunity to give regularly if I were an Information Science Professor teaching at any of your universities.

That’s why the title of my talk is: “The most innovative methods are sometimes the simplest.” (I admit, that in the interest of drawing you in, I almost omitted the word “sometimes.”) I could have also titled this presentation: “It is more important to ask a good research question than to have a cool research method.”

But, I wanted you to come, so you got the more click-baity title.

Underneath what will be a somewhat lighthearted talk are some serious issues that plague academia—ones that I’d be happy to take questions on at the end—that I will only quickly brush upon here. Each one of these issues could be the basis for a keynote. And each one raises questions that I think about because my subject matter is academic careers and scholarly communication, but also because I faced them myself when I was a graduate student.

- For all the critiques of publish-or-perish culture, the pressures to publish keep growing.

- For all the critiques and counter-movements, the importance of accumulating citations or otherwise rising in various metrics continues to persist.

- Not unrelated to the previous points, disciplinary posturing and positioning (i.e., “staking your ground” as a scholar of a given field) continue to play a role in determining how you approach your scholarship.

- Again, not unrelated, the journals you are pressured to publish in (or, at best, nudged towards) often predetermine the questions and methods you can use.

These problematic elements of academia draw a terrain through which there are only a few easily identifiable paths to success.

Obviously, we could go into more detail about each of these issues and beyond. But I simply want to point out that these—I would say, problematic—elements of academia draw a terrain through which there are only a few easily identifiable paths to success:

- Publish a lot by applying known methods to new datasets or areas. Information science is FULL of these kinds of scholars.

- Invent, or borrow from other disciplines, new methods and use them to offer novel insights into old problems. Computer science is increasingly popular here.

- Or, if you really want to stand out quickly, invent or borrow a method, apply it to a novel question, and then crank out a whole bunch of papers quickly as you ask that question over and over again.

What I want to do with my remaining time today is walk you through how I have managed to, on multiple occasions, use extremely simple methods to shed light on questions in an innovative way. This has allowed me to not get caught up in the disciplinary struggles, nor to find myself playing the game of cranking out endless meaningless publications. I hope that some parts of this trajectory will resonate with where you are at, and hopefully serve you well as you proceed in your own academic careers.

My academic story begins when I was a doctoral student. I had been working in Latin America and had been trying to better understand Latin American scholarly publishing, which is largely all Open Access. I knew I wanted to do my dissertation on this topic. I had worked with three major regional players who, by combining their resources, provided me with access to a directory of every journal in the region, the metadata of over 1300 journals, the download data of the same journals dating back years, citation data for about half of those journals, and more. I also had the distinct advantage of having a computer science background, so I possessed the computation skills to manipulate and crunch this data, plus the mathematics knowledge to be able to understand—even if I had not yet learned—sophisticated statistical methods.

I was doing my PhD in a School of Education, and so my own background and the data I had access to gave me a competitive advantage over many of my Ed School colleagues. It became clear to me that, to “succeed” in academia, I should deepen my methodological expertise and further distinguish myself from my peers. So I set about trying to do this:

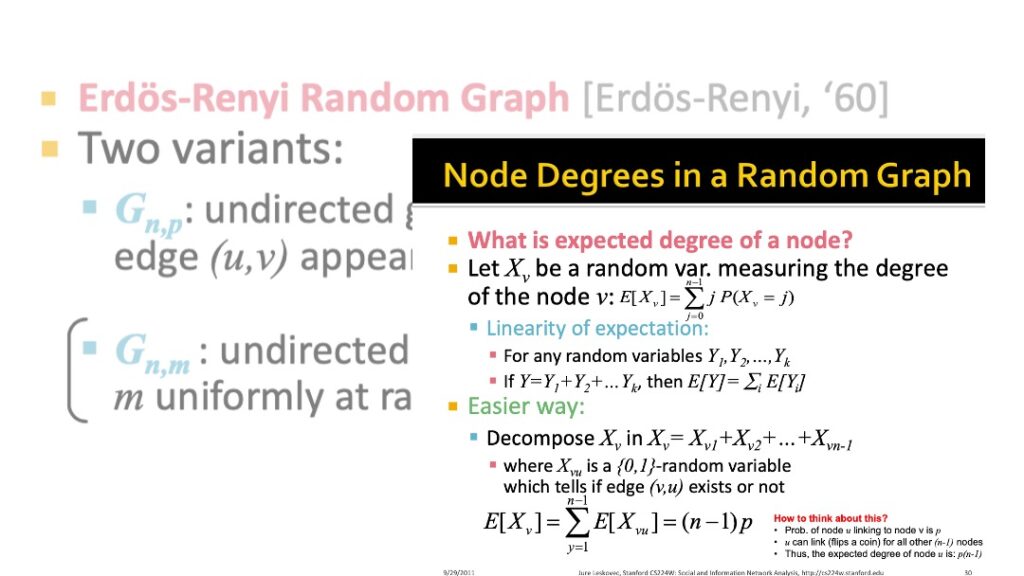

I took a class on network analysis, as well as multiple workshops, and then struggled for weeks to figure out how to run some Erdős–Rényi (Random Graph) models. This approach is the equivalent of using a “normal distribution” in statistics—you can compare your graph and see if it differs from a randomly generated one. I was going to use this to see how national, regional, and international networks behaved.

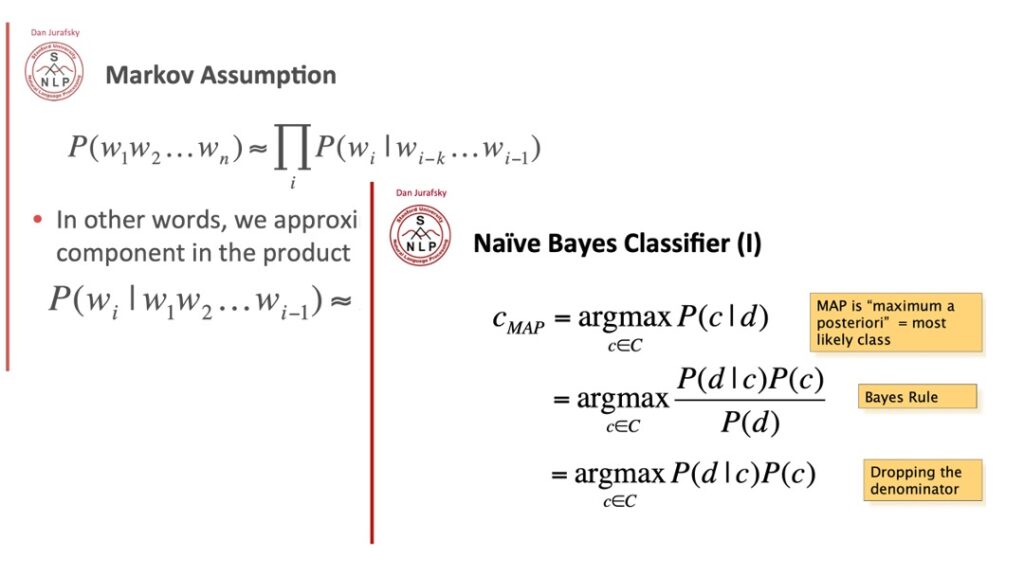

Then I took a class on Natural Language Processing, and I learned how to do topic modelling—labelled and unlabelled, supervised and unsupervised, etc. I learned a whole complicated suite of methods for figuring out what articles clustered with each other, all to see if I could figure out if Latin American scholarship was engaging more with itself than with scholarship from beyond.

My point is this: I had a unique dataset and a massively understudied problem space, so almost any question I wanted to tackle could have produced valuable insights. I struggled, until I realized that what I really wanted to know was who was using this research. I kept trying to find a clever statistical, computational, or quasi-experimental way of answering the question: “Who uses this stuff?”

Until I realized the solution: JUST ASK THEM.

OK, at this point, you might say: “But this particular solution only worked because you had access to the portals.”

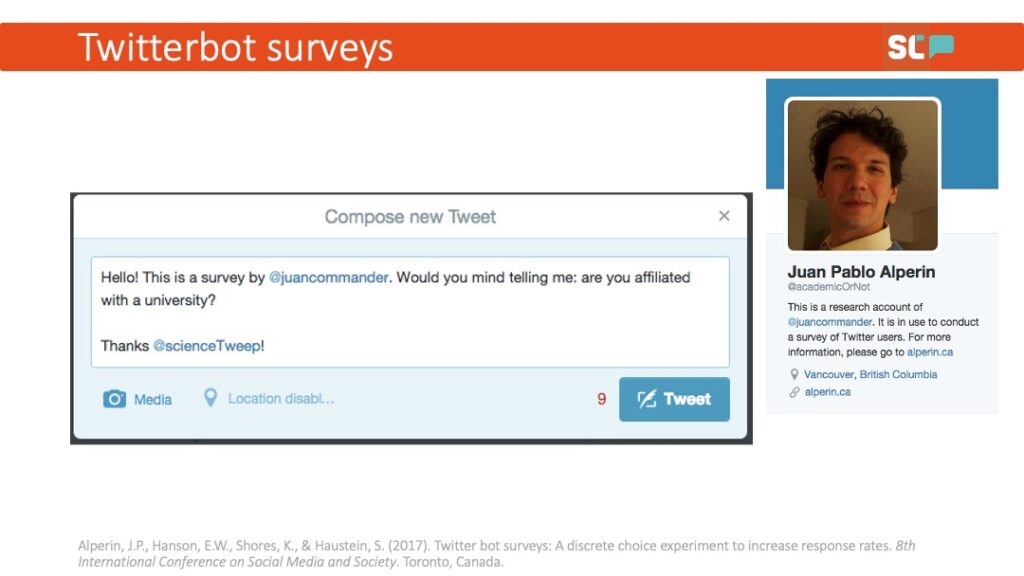

While that may be true, I came across the same problem when I was trying to make the argument that social media could allow members of the public to access research. It was the earliest days of what are now known as Altmetrics, and lots of folks had been trying to answer the question: “Can we know whether the public reads research by looking at social media?” I had just come off the high of doing this super simple pop-up survey, so I thought: How can I replicate this? Say “hello” to the creation of Twitter-Bot Surveys.

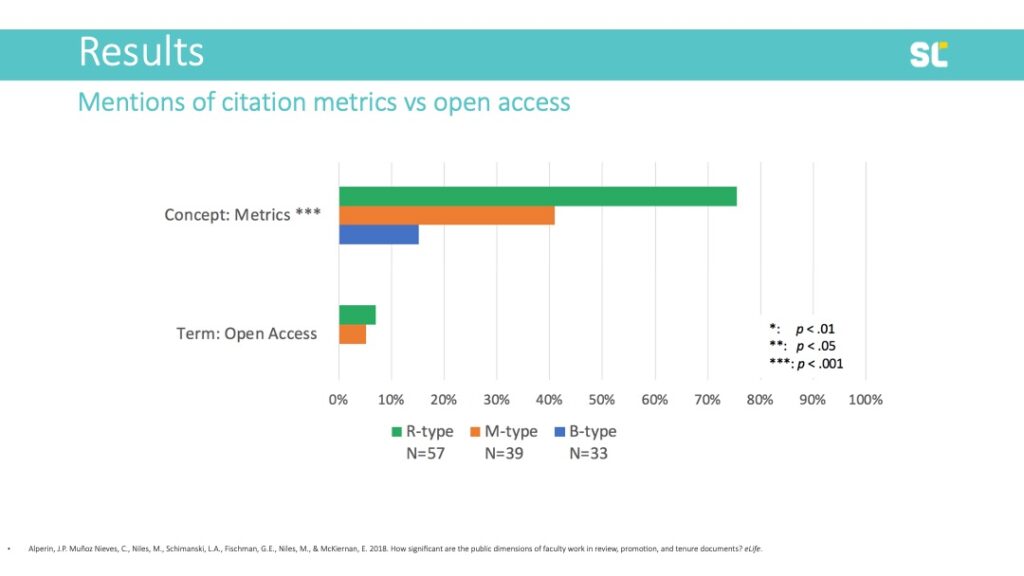

For those of you who fall more on the library side and are interested in documents and textual corpora, the same sort of approach can apply beyond social media. The conversations about the various issues I outlined earlier—those issues about the need for many publications, the rising importance of metrics, etc—all seemed to come back to the incentive structures in academia. The argument I kept hearing was that faculty wanted to do things differently, but review, tenure, and promotion (RPT) committees kept evaluating people in this way. We even saw a proposal to run an advocacy campaign to “change the form” of the RPT process—all based on no evidence.

And so, our team came up with what was, again, a pretty simple method to determine whether this argument actually reflected reality: we collected documents related to the Review, Promotion, and Tenure process. How? We just emailed people and asked them for them! Obviously, we did some planning around sample sizes, etc. But the plan was simple: collect documents and then check whether the terms of interest were present in the texts or not. Again, this method is not complicated. Instead, what is innovative here is the use of a simple method to answer an important question.

This is what I want to emphasize: although I have accidentally become one of those scholars who is known for innovative methods, I really don’t think any of these are innovative at all. There are some really clever studies out there using really clever methods, but, in most of my work, I don’t think the methods are innovative or sophisticated at all. Pop-up surveys already existed at the time I used them, as did twitter bots, and checking the presence of specific terms in a collection of documents is about as simple an analysis as you can imagine. What has made these papers and studies successful? Why do I—and, I think, others—consider them to be so interesting?

They ask questions that people—and not just a select few—really want to know the answers to. I really cared about the “so-what” during all of these research projects. When you do that, it frees you from the pressure to get a perfect answer. If the answer is important, having a complete answer is not essential. That is, instead of trying to answer a boring question in a clever way, it is better to answer an interesting question in a boring way.

If the answer is important, having a complete answer is not essential. That is, instead of trying to answer a boring question in a clever way, it is better to answer an interesting question in a boring way.

Ask a good question and look for a “good enough” way to approximate an answer. If your question is good enough, a perfect answer is not necessary.

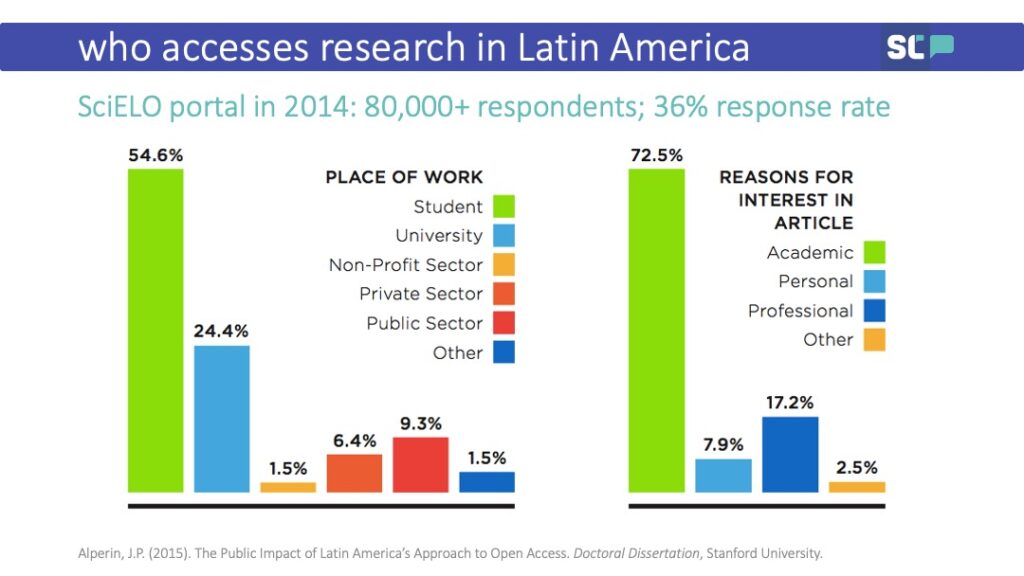

I want to go back to the earliest example I gave—the one about who was reading Latin American scholarship. Did my method control for all demographics? No. Could I have tried to get multiple answers and link them together to form a more complete picture of the users of Latin American research? Yes. What about linking those answers to Erdős–Rényi models? Sure! You could do that. But, at the end of the day, the most compelling thing to come out of my PhD was the answer to a pop-up question: “I am interested in this research article for my personal use.” This view was expressed by 25% of respondents.

It was incomplete, it was imperfect, but, as it turned out, it was also an innovative way to very simply answer a question that everyone in the Open Access movement cared about.

By all means, come up with clever studies, think through all the interesting angles you can, make your research as robust as possible… But my advice is to first spend time thinking about what question you really care about and why.

By all means, come up with clever studies, think through all the interesting angles you can, make your research as robust as possible. Do high quality work. This is all absolutely essential. But my advice is to first spend time thinking about what question you really care about and why. Only after you are clear on that question should you figure out how innovative your method needs to be. It might turn out that, just as with the examples I’ve shown you today, often the most innovative thing you can do is to answer your question as simply as possible.

Thank you.