By Mario Malički and Juan Pablo Alperin

This blog post is inspired by our four part series documenting the methodological challenges we faced during our project investigating preprint growth and uptake.

Interested in creating or improving a preprint server? As the emergent ecosystem of distributed preprint servers matures, our work has shown that a greater degree of coordination and standardization between servers is necessary for the scholarly community to fully realize the potential of this growing corpus of documents and their related metadata. In this post, we draw from our experiences working with metadata from SHARE, OSF, bioRxiv, and arXiv to provide four basic recommendations for those building or managing preprint servers.

Toward a better, brighter preprint future

Creating a more cohesive preprint ecosystem doesn’t necessarily have to be difficult. Greater coordination and standardization on some basic metadata elements can continue to allow a distributed approach that gives each community autonomy over how they manage their preprints while making it easier to integrate preprints with other scholarly services, increase preprint discoverability and dissemination, and develop a greater understanding of preprint culture through (meta-)research. We believe this standardization can be achieved through voluntary adoption of common practices, and this blog post offers what we believe would be useful first steps.

We understand that preprints servers often lack the human and material resources needed to ensure the quality and detail of every record that is uploaded to their systems. However, we believe many of the recommendations set out below can be carried out with relatively low cost by improving preprint platforms. These investments can be made collectively by various preprint communities. To help, we have included links to open-source solutions that might be used to support the work. We also invite and encourage others to share their experiences and insights so that we can update this post with additional best practices.

Recommendation #1: Clearly identify each record’s publication stage

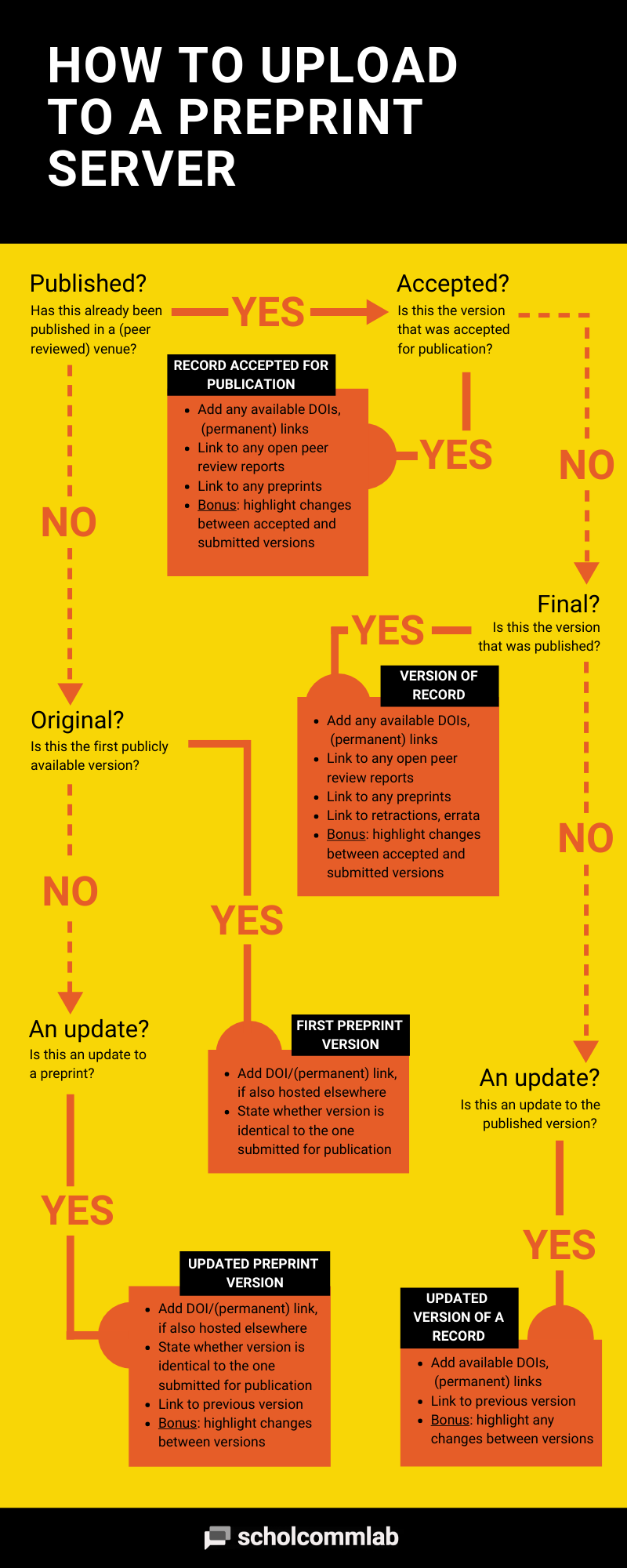

Our most basic challenge when working with metadata of preprint servers was the inability to identify which records were preprints and which were published (peer reviewed) papers. While a definition of what constitutes a preprint is not universal,1 we highly recommend adopting a basic taxonomy of documents and document versions so that it becomes possible to clearly distinguish between the following types of documents:

- unpublished record (preprint): This record is usually posted for fast dissemination to the research community or for obtaining feedback. It has never been published in a peer reviewed venue (e.g., scientific journal, conference proceedings, book, etc.). In some research communities, the initially posted version or an updated version (see below) may also represent the final scientific output—that is, it will never be sent for peer review or publication in a traditional publishing venue. In Crossref, this type of record is classified as “posted content.”

- published (peer reviewed) record: This record has already been published (or accepted) in a peer reviewed publication venue. The corresponding Crossref classifications include journal articles, books, conference proceedings, and more.

We are aware that some currently existing preprint servers only accept one of these two record types, while others facilitate direct submissions of records to scientific journals, or vice versa. Nevertheless, in order to capture all aspects of scientific publishing and enable integration with existing scholarly services, we would highly recommend universally adopting this basic classification and including it in the metadata.

We also recommend that servers go a step further, providing additional information about these two types of records, so that researchers and stakeholders can better understand and follow the full lifecycle of scientific outputs. Based on our research, we recommend this more detailed taxonomy:

- unpublished record (preprint):

- first preprint version: the first version shared with the public.

- updated preprint version: an updated version of a previously posted preprint. Ideally each updated version should contain a version number and include description of what has changed from the previous version (see our third recommendation below).

- published (peer reviewed) record:

- record accepted for publication: the version of the record that has been accepted for publication (i.e., after peer review but before final typesetting and editing). In Crossref, this type of record is classified as “pending publication.”

- version of record: the version as it appears in another publication (e.g., scientific journal, conference proceedings, book, etc.)

- updated version of record: a revised or updated version of the version of record. It may include changes introduced due to post-publication comments or discovered errata.

A visual breakdown of this taxonomy, along with suggestions from our following two recommendations, are incorporated in this flowchart:

Recommendation #2: Link related records

Improving understanding about the lifecycle of preprints and published records and increasing trust in their use will require that researchers and users are able to understand the relationship between preprints and other records. For this reason, we highly recommend servers make every possible effort to link the record types we mentioned above to one another, even when those versions are not stored on the same preprint server. We also recommend linking records with (open) peer review reports whenever possible.

Some servers currently link records by letting submitters enter a link, DOI, or description in a free text field to indicate connections between records. Others attempt to link records automatically. Although, in theory, these are great strategies, they don’t always measure up in practice. Our analysis found that a significant number of the links that were available on SHARE, OSF, bioRxiv, and arXiv were incorrect or incomplete There were also many instances where the free text fields had been used to enter other types of information, like comments, author affiliations, or dates.

To prevent errors like these, we recommend that preprint servers ask users to state the type of record they are linking to during the upload stage, and then confirm that the links they enter work (i.e. can be resolved). Servers could also check the Crossref/Datacite metadata (if a DOI link exists) or read the metatags on the linked page to confirm whether the document is, in fact, related. These checks could either take place during data entry or on a regular basis, using email notifications to alert authors of potential errors.

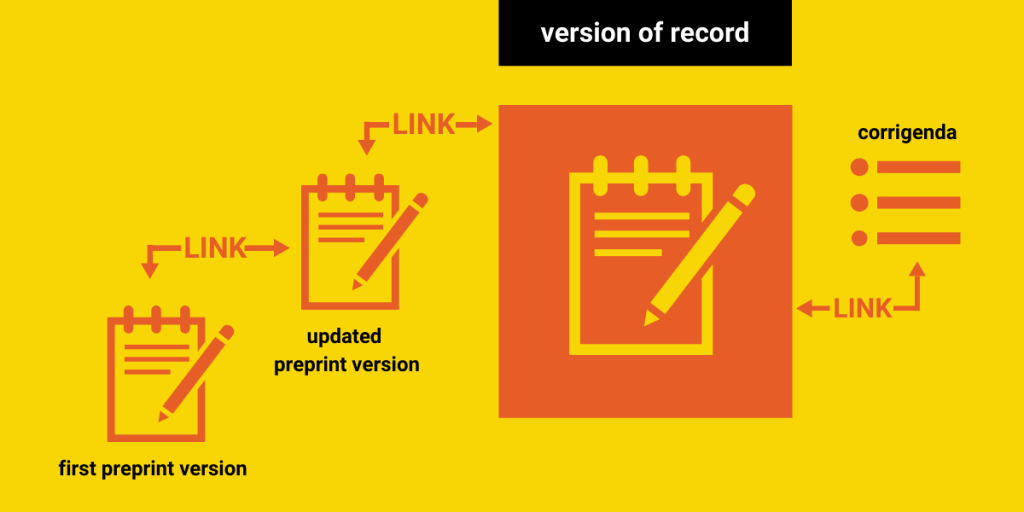

Additionally, some published versions of a record may be amended by errata or corrigenda, or be retracted. In our own research, we noticed that even preprints themselves can be retracted. All of these changes and corrections should be clearly linked to the record in question, so that stakeholders are aware of the latest status of the publication, especially if it has been found invalid in its results.

If server moderators or authors feel that records should be removed, clear reasons for doing so should be stated. We recommend servers put firm policies in place surrounding errata, corrigenda, and retractions, and consider following the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)’s recommendations on these issues. Any removal or retraction notices, as well as alerts related to any aspect of publication ethics, should ideally follow a standardized format. We also recommend including both a description of the actions undertaken by the server moderators, as well as a comment from the authors about those actions. More information on the issues surrounding retraction notices, as well a retraction notice template, is available at the Scientist.

Recommendation #3: Label preprint versions and describe version changes

One of praised differences between preprints and traditional publications is that preprints can be more easily revised and updated. A description of a manuscript’s evolution over time (including its movement through the publication stages described above) could offer important insights into the value of posting preprints.

However, in our own research, we were only able to determine the number of documents that had been revised on two of the four servers we studied: bioRxiv and arXiv. We are also unaware of other, more detailed studies exploring the evolution of documents throughout the publication lifecycle. For this reason, we recommend that servers capture and display the revision history of every document in their collection.

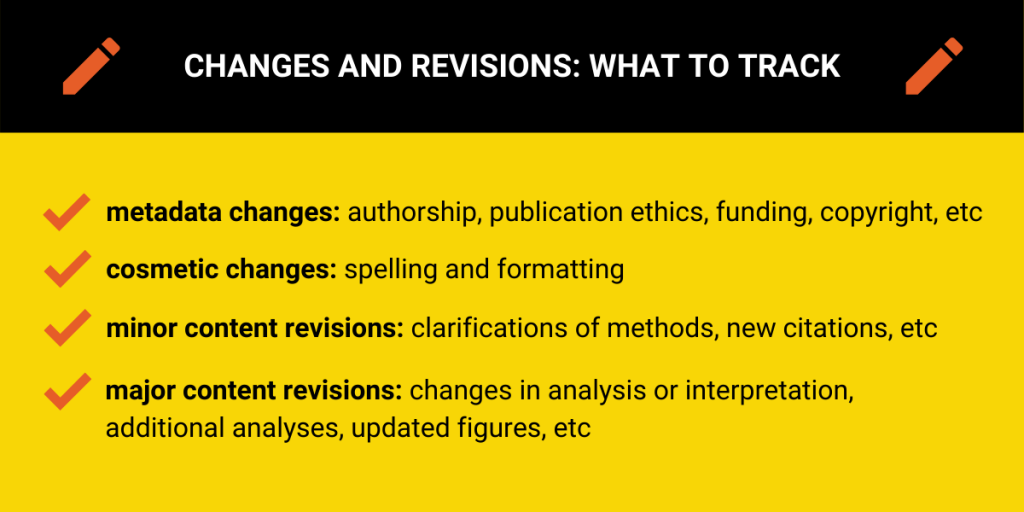

At a minimum, we recommend that all preprint servers track revision numbers and keep previous versions of documents and metadata available for review. Ideally, identifying revision history would also capture some indication of what changes occurred between versions. To this end, we suggest tracking changes along four dimensions:

- metadata changes (e.g., in authorship, publication ethics, funding, or copyright)

- cosmetic changes (e.g., spelling and formatting)

- minor content revisions (e.g., clarifications of methods, introduction of new citations, etc. )

- major content revisions (e.g., changes in the analysis or interpretations, additional analyses, updated figures, etc.)

We realize that what constitutes a major or minor revision may differ between communities, but we are less concerned about a rigorous determination of the extent of changes than we are with some general indication of what has changed. For example, in our research we often saw small stylistic corrections posted only minutes after the posting of a preprint. These kinds of changes are quite different from the major revisions to an analysis that might be made after receiving community feedback—and we recommend that the revision history reflect this difference.

Servers should also make it clear to authors during the submission process whether small or cosmetic changes can be made to uploaded documents, or whether making any changes will require the creation of a new version (and associated metadata). Servers could also consider providing additional details on exact differences between versions (e.g., the number of words, figures, tables, outcomes, references, etc.) by use of automation or by providing a free text field for users to describe the differences in their own words. For those depositing preprint metadata to Crossref, we recommend that DOIs between versions be linked according to Crossref’s recommended practices (i.e., by using the intra_work_relationship tag with the “is Version Of” type).

Recommendation #4: Assign unique author identifiers and collect affiliation information

Just as tracking the number of preprints is fundamental to understanding preprint uptake, so is knowing the number of individuals who are participating in the practice. Universally adopting author identifiers, both within and between preprint servers, would greatly facilitate future research in this area analysis. That said, we understand that there are communities who disagree with such centralized tracking of individual outputs. As such, we recommend that those who are comfortable with the use of global identifiers do so, and that those who are not focus on improving their handling of author names and identities.

To this end, we recommend that, at the very least, servers assign an internal identifier to each author and co-author. Alternatively, they could collect or include identifiers from existing systems (e.g., ORCID iD, Scopus or Researcher iD, Google Scholar iD, etc.). The goal here should be to reduce the difficulties in disambiguating author names so that it is possible to know when two records are authored by the same individual. Otherwise, small differences in spelling, the use of non-English marks (i.e. diacritical marks), or other tiny discrepancies can make doing so almost impossible.

We would also highly recommend that providers allow users to include information about shared or equal authorship or corresponding authorship when uploading a record, as these data are widely used in bibliometric analysis and are relatively easy to collect.

In addition to helping standardize author names and including an identifier for disambiguation, preprint servers would benefit from collecting affiliation information for each author. Ideally, each affiliation should also have an accompanying identifier, making use of established systems like Ringgold Identifier (proprietary) or the emerging Research Organization Registry (open). If using an identifier isn’t possible, we recommend collecting country and institutional affiliation as individual fields, with auto-complete features to help standardize names between preprint servers.

Final considerations

These four recommendations represent our main suggestions for improving the state of the preprint ecosystem. We believe that implementing these recommendations would increase trust in and discoverability of preprints, and would allow researchers to undertake the same (meta)studies that have so far mostly been done on published journal articles or conference proceedings.

This list of recommendations is by no means exhaustive. In our next post, we will provide additional recommendations that preprint moderators could consider. We also welcome feedback and additional suggestions for best practices that we can add to the list. As the scholarly landscape evolves, preprint servers need to evolve with it. We hope these recommendations help make that evolution possible.

To find out more about the Preprints Uptake and Use project, check out our other blog posts or visit the project webpage.

Statement of Interest: JPA is the Associate Director of the Public Knowledge Project who is currently developing an open source preprint server software in collaboration with SciELO.