Analyzing preprints: The challenges of working with OSF metadata

By Mario Malički, Maria Janina Sarol, and Juan Pablo Alperin

This blog post is the second in a four part series documenting the methodological challenges we faced during our project investigating preprint growth and uptake. Stay tuned for our next post, in which we’ll describe our experiences with the bioRxiv metadata.

Our analysis of the SHARE database, described in our previous blog post, revealed many challenges of working with metadata that was merged from different preprint servers. To continue with our research, we needed to proceed with a detailed analysis of one server (provider) at a time. We decided to start with preprint servers created by, or in partnership with, The Center for Open Science (COS). Using their Open Science Framework (OSF) preprints infrastructure, COS launched its first interdisciplinary preprint server, titled OSF Preprints, in 2016, and in the years following helped launch additional 25 servers (Figure 1 below), each tailored for a specific discipline or country. We downloaded all 29,430 records available through the OSF API on June 18, 2019 and explored the main metadata fields, just as we had done for SHARE (documentation on OSF server metadata fields is available here).

1) Sources and records per source

While we could easily calculate how many records existed on each of the 25 servers, we soon realized that records do not necessarily correspond to preprints. Identifying preprints among the records ended up being more challenging than we had anticipated for a number of reasons.

First, although servers employing the OSF infrastructure can accept different types of records, there is no metadata field (or filter on the OSF search engine) to distinguish between them (SHARE metadata also lacks such a filed). Our exploration revealed that several of the records were postprints (i.e., published, peer reviewed papers (e.g., example one), full conference proceedings containing several papers (e.g., example two), PowerPoint presentations (e.g., example three), or Excel files (e.g., example four). Some of the records were also theses, with one of the servers, Thesis Commons, created specifically for this document type.

Second, we identified a significant number of duplicate records which, if left accounted for, overestimate the number of preprints or records available. By using a strict exact matching of titles and full author names, we found 1,810 (6%) duplicate OSF records. These records corresponded to 778 unique title and author pairs that had been reposted at least once on either the same OSF preprint server (e.g., example one: records one and two, Figure 2, below) or on different servers (example two: records one, two, three, four, and five, or example three: records one and two).

This number, however, underestimates the actual number of duplicates, as users creating these records on OSF servers sometimes enter slightly different information. For example:

- different authors for the same record, as in example four: records one and two;

- different spellings of an author’s name or omission of an author’s middle name, as in example five: records one and two; or

- uploading the same records in two different languages, as in example six: records one and two.

To reliably identify all of the duplicates, we’d need a more detailed comparison of titles, names abstracts, and linked published papers (outlined later in this post).

Third, 96 (0.3%) records we identified had been withdrawn at some point. But unlike for published papers, for which the Committee on Publication Ethics recommends keeping the full text of the record available after indicating its retracted or withdrawn status, withdrawn documents on OSF are removed, leaving behind only the webpage and none of the content. This makes it impossible to determine if withdrawn records were indeed preprints or some other kind of document. Reasons for withdrawal were listed on the webpage and available in the metadata for 70 (73%) of records. But while some withdrawal reasons were written by the server moderators (e.g., example one), some by the authors (e.g., example two), there were also cases where it was not clear who wrote them (e.g., example three, Figure 3). No (metadata) information was available on the individuals who provided the reasons for withdrawal.

Additionally, we found six orphaned records, for which the metadata existed in the database, but the webpage was no longer accessible. We could not find explanations on the differences between orphaned and withdrawn records, except for OSF’s orphaned metadata definition, which reads: “A preprint can be orphaned if it’s primary file was removed from the preprint node. This field may be deprecated in future versions.”

2) Subjects (i.e., scientific discipline or subdiscipline classification)

OSF servers use the bepress discipline taxonomy for classifying records to scientific fields, albeit with slight modifications. For example, bodoArXiv, a server for medieval studies, introduced Medieval Studies as a top level discipline, while the bepress taxonomy has Medieval Studies under the Arts and Humanities top-level discipline. Similarly Meta-Science and Neuroscience were introduced as a top-level disciplines in PsyArXiv, while in bepress Meta-Science does not exist as a separate sub-discipline, and Neuroscience falls under the top-level Life Sciences discipline. Only two of the records we identified did not have subject classification.

3) Dates

OSF metadata contains seven date fields, two of which we planned to use for our analyses: date_published (defined as “the time at which the preprint was published”) and original_publication_date (defined as: “user-entered, the date when the preprint was originally published”). The definition of the other five date fields (date_created, preprint_doi_created, date_withdrawn, date_modified, and date_last_transitioned) is available here. The date_published field appears to be automatically populated, and was therefore present for all records. Original_publication_date, on the other hand, was entered by users for only 9,894 (35%) records.

We also found instances where the original_publication_date differed from the date listed in Crossref metadata (e.g., example one, the user entered date is February 13, 2018, but Crossref lists February 14; example two, Figure 4 below, the user entered December 31, 2008, but Crossref lists December 3, 2009). These kinds of discrepancies make it difficult to identify which records correspond to preprints (i.e., by comparing the date when a record was created on a preprint server with the date it was published as a peer reviewed paper). They also pose challenges for determining at what stage of the dissemination process authors uploaded the preprint (i.e., on the same date they submitted a paper to a journal, or at the time of the paper’s acceptance).

4) Contributors

In our previous blog post, we explained how in SHARE, Contributors were divided into Creators (authors) or Contributors (uploaders). In OSF, Contributors are also divided into two similar categories: bibliographic, those that are the authors of the record, and non-bibliographic, those that can upload (new) versions of the records. We found 2,278 (8%) records that had at least one non-bibliographic Contributor (uploader), but only 14 (1%) of those records also listed one of those uploaders as an author. This confirms, like that data in SHARE, that uploaders are rarely also the authors of the records they are uploading, and indicates users are likely misunderstanding the entry fields during preprint uploading.

We identified many of the same issues that plague the Contributor field in SHARE, also in the OSF metadata. When taken together, these issues make the author metadata unreliable for authorship network analysis and other scientific inquiries. For example, we identified cases where the correct number of authors in the metadata differed from the number of authors listed in the uploaded documents (e.g., example one: only one author is listed on the record, but three can be found in the uploaded PDF).

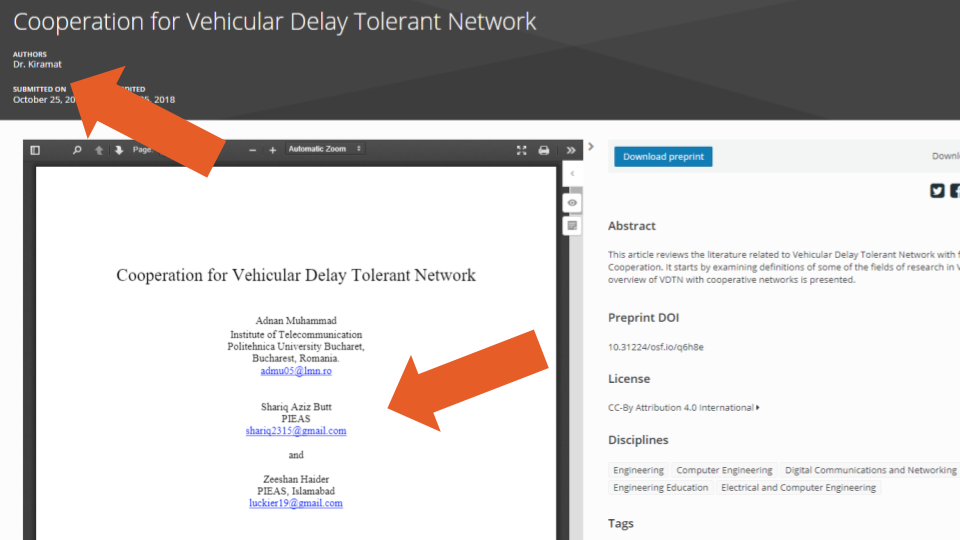

We also encountered cases where Contributors that were specified as non-bibliographic should have been bibliographic (e.g., example two: the metadata lists one bibliographic and five non-bibliographic authors, while the uploaded PDF lists all six as bibliographic authors), as well as cases where the authors listed in the metadata were not among the authors listed in the uploaded PDF (e.g., example three, Figure 5 below: the single author in the metadata differs from the three listed in the uploaded PDF). Additionally, there were 31 (0.1%) records where the same author (using simple exact full name matching) was listed more than once as an author on the same record (e.g., example four).

When we dug deeper into the analyses of authors’ names, we also saw that 137 (0.5%) records were missing an author’s first (given) name or initials (e.g., example one), and 2,091 (7%) were missing a last name (e.g., example two). We also found instances where users listed the name of a journal as the name of the author (e.g., example three, Figure 6 below), the name of a proceeding (e.g., example four) or of an institute (e.g., example five), and cases where the professional titles were included in names (e.g., example six).

Additionally, like in SHARE, we found inconsistencies regarding the position of authors in the byline order (i.e., their place in the list of authors). We identified 67 cases where two or more authors had the same position in the byline order according to the metadata information, and to the best of our knowledge none of these cases where due to the practice of equal or shared contributorship (e.g., example one: the last two authors share the byline order position according to the metadata, but not according to the uploaded PDF; example two: the first two authors share the byline order position according to the metadata, but not according to the uploaded PDF). Finally, we also identified cases where the byline order in the metadata was completely different than the one in the uploaded document (e.g., example three).

As a final remark on the Contributor field, we noted that information on authors’ affiliations is not (directly) included in the record’s metadata; it is available only for authors who have created an OSF account and have taken the time to fill in their employment information. That is, uploaders who post preprints on the OSF servers are not asked to fill in affiliation information or professional identifiers (e.g., an ORCID iD) for themselves or for their co-authors at the time of the preprint upload. Instead, co-authors are sent an email by the system asking them to create an account, and if they choose to do so, they are then prompted to include their identifiers, education, and professional affiliations (but none of these fields are mandatory). Moreover, because this metadata is linked to the user and not the preprint, it can easily introduce errors and inconsistencies, as affiliations change over time. There were 9,741 (33%) records for which at least one of the co-authors did not create their profile on OSF. Of the 17,510 unique users that did create their profiles, only 3,218 (18%) provided their affiliation information.

Additional exploration of OSF servers

Despite all of the issues with the basic OSF metadata we described above, we still wanted to include OSF servers in our analysis of preprint growth and uptake. To help estimate the number of unique preprints (not records) on the servers, we explored an additional metadata field that we did not explore in SHARE: a record’s link to its published peer reviewed version.

Like many other preprint servers, OSF servers offer a free text field to allow users to link their preprints to their published (likely peer reviewed) version. This can be done at the same time the preprint is uploaded (if the published version already exists), or at any time after it becomes available. However, on OSF, the field is labelled “Peer-reviewed publication DOI”, which means that preprints cannot be linked to papers published in venues that do not assign a DOI. We found 4,965 (17%) records with a peer-reviewed publication DOI.

However, after exploring the data, it became apparent that this field alone cannot be used as a clear indicator of whether or not the record corresponds to a preprint (e.g., example one, where the peer-reviewed publication DOI points to an identical PDF that was uploaded as a preprint). In 491 (10%) of cases, the “peer reviewed” DOI pointed to another OSF preprint (e.g., example two, where the DOI points to a duplicate of the same record). Furthermore, 70 (14%) of the records used the record’s own DOI as the peer-reviewed publication DOI (e.g., example three, Figure 7 below). We also identified cases where the DOI entered could not be resolved (i.e., link does not work, as in example four). In addition, we found 362 (7%) cases where DOIs pointed to preprints or data deposited at the Zenodo repository and 9 (0.2%) cases were they pointed to items deposited at the Figshare repository. Finally, we found 305 (6%) records that shared the same Peer-reviewed publication DOI with at least one other record in an OSF repository. In many cases, this was due to the preprints being duplicates of each other, but in others, the error seemed to be a data entry issue (e.g., example five: records one and two are different preprints that point to the same published paper).

Proceed with caution

As can be seen from above, using OSF metadata to answer even the most basic questions about preprints growth and uptake is problematic. The contributor metadata, in particular, was very unreliable, making it difficult to conduct any analyses that relied on author information, including searching for possible postprints using the authors names. We therefore caution researchers and stakeholders citing the number of preprints as reported on the OSF website or in recently published scientific articles1,2,3. To the best of our knowledge, no analyses conducted so far have fully addressed the issues we encountered.

Note: We communicated many of the issues described above with the OSF team at the Centre for Open Science who have indicated they are taking steps to address them. The most recent version of the OSF roadmap is available here.

References

- Narock T, Goldstein EB. Quantifying the Growth of Preprint Services Hosted by the Center for Open Science. Publications. 2019;7(2):44.

- Rahim R, Irawan DE, Zulfikar A, Hardi R, Gultom E, Ginting G, et al., editors. INA-Rxiv: The Missing Puzzle in Indonesia’s Scientific Publishing Workflow. Journal of Physics: Conference Series; 2018: IOP Publishing.

- Riegelman A. OSF Preprints. The Charleston Advisor. 2018;19(3):35-8.

Comments? Questions? Drop us a line on Twitter (tag #scholcommlab). We have shared the issues outlined above with the COS team, and welcome your insights and experiences with working with preprint metadata. Our source code is available on GitHub.

[…] our analyses of SHARE, OSF, and bioRxiv metadata, (which you can read about here, here, and here), we went on to explore the metadata of arXiv’s Quantitative Biology […]

[…] related metadata. In this post, we draw from our experiences working with metadata from SHARE, OSF, bioRxiv, and arXiv to provide four basic recommendations for those building or managing preprint […]

[…] the challenges working with SHARE and OSF metadata (read about them in our previous blogs here and here), we explored the metadata of bioRxiv—a preprint server focused on biology research. Since its […]